“You’re fired. Get out — you talentless fool.”

(and how Marina flipped the board so she wasn’t the loser)

A meeting that felt like a meat locker

Buckwheat rattled softly in a clay bowl — Anna Petrovna (Alla Viktorovna at the office) was picking out black specks as though the fate of the family depended on their purity. It was her ritual to steady herself before each “lesson for the daughter-in-law.”

“Lena, five years,” she said in a machine-flat voice. “Five years! And nothing to show for it.”

I kept washing dishes, swallowing my retorts under the running tap. But a hard knot was tightening in my chest.

The phone rang: “Marina, come to my office.”

A flat, colorless tone — the voice of a machine, or a mother-in-law who has decided to start a war.

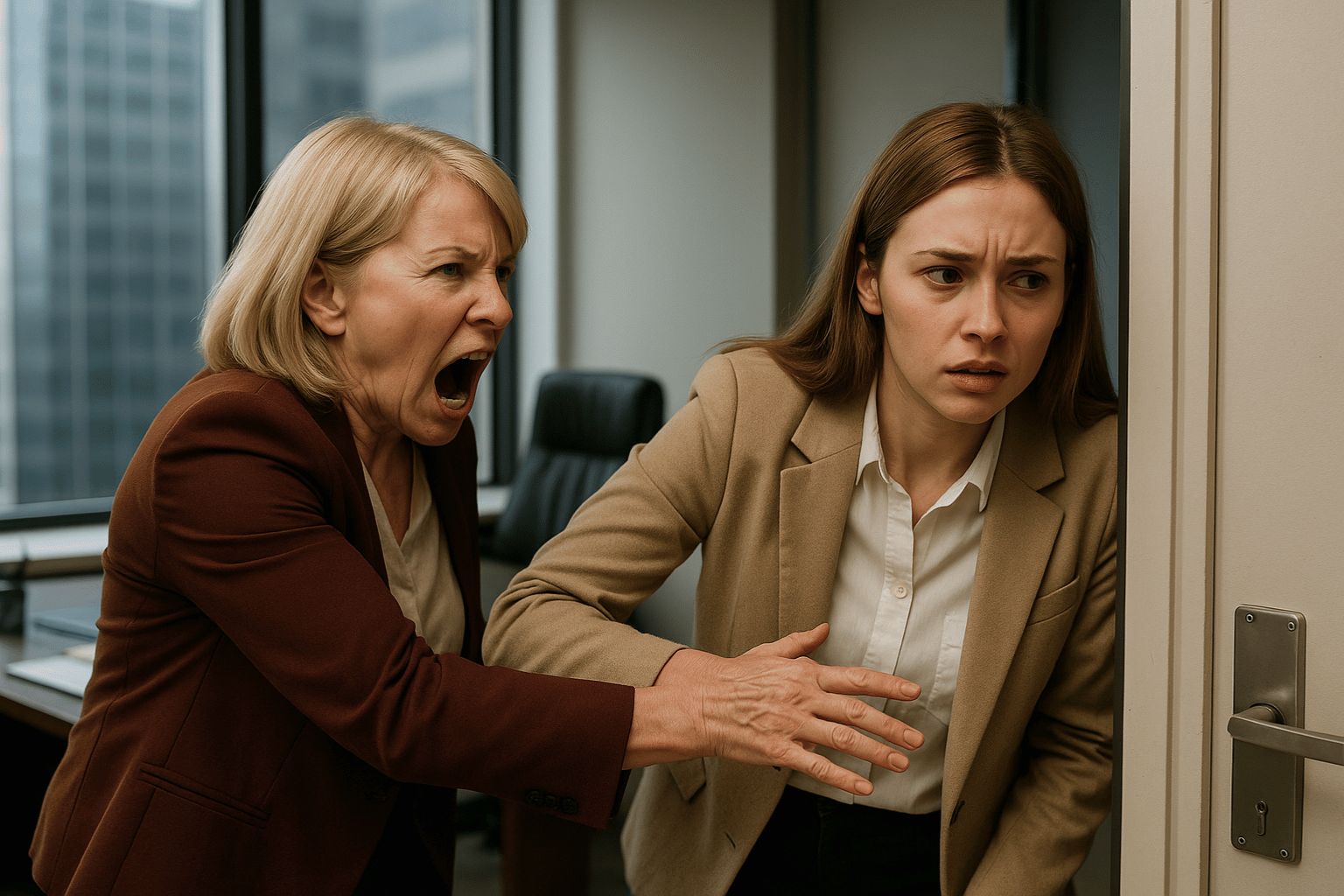

Her office was as cold as a freezer. People walked in with careers and walked out without even self-respect.

Marina (I) knocked, went in, nodded. Beyond the glass, Moscow-City glittered — and the shards of my confidence seemed to be falling through the skyline.

“There’s a problem,” said Alla Viktorovna, laying down a file, lips pressed ruler-straight. “A serious shortfall in last quarter’s reports. Nearly six million. Every page bears your signature.”

I sat without leaning back, just resting on the edge as if on a cliff lip. The corner of my mouth twitched into that hateful strained smile that embarrasses you even in the mirror.

“Are you serious, Alla Viktorovna? I’m not a trainee. Every figure I sign, I can vouch for with my head. Check the revision history.”

“We did,” she cut in. “Everything is… flawless. Signatures, formulas. At best, sloppy. At worst — deliberate.”

“A setup?” my voice rasped. “I triple-check before I sign. Who would even—”

“That’s enough, Marina. You’re terminated for cause.”

I exhaled. “Does Dima know?”

“Of course. He agrees.”

The floor gave way. I hadn’t expected heroics, but siding with his mother for the killing blow? After eight years of marriage and two mortgages, I still wasn’t ready for that.

I stood. No scene, no tears. I left one sentence at the door:

“You don’t need a daughter-in-law, Alla Viktorovna. You need a mirror to whisper at: ‘Brilliant, successful, strong… and lonely as a tree on an empty plain.’”

The registered letter, the “grocery money,” and silence

Then came the B-movie sequence: registered letter, company accounts cut off, messenger blocked. From my husband — total silence. He vanished like the alley cat. One transfer only: 5,000 rubles — “for groceries.”

Sweet. Just when I’d planned to sauté some humiliation and plate it with disappointment.

On day three after the firing, my phone rang. Unknown number, familiar voice.

“Marina, it’s Nikolai Petrovich.”

I almost dropped my cup. My former father-in-law — the man who left Alla long ago to build houses in Krasnodar. Literally: build them.

“I’ve heard,” he said, voice low and steel-sure. “I want to meet. Talk. Maybe… offer work.”

I was quiet a long moment. “Should I trust you?”

“It’s not about trust,” he said. “It’s about justice. And your chance to play a knight’s move.”

We met at a café on Tverskaya. Gray coat, eyes tempered by fire — cool and warm at once.

“I left that family, not my sanity,” Nikolai said. “Alla is stirring the same old mud. I have a plan. I need a reliable accountant. You fit.”

I gave a bitter laugh. “They humiliated me in a meeting and shoved me out the door. My husband co-signed it. And you want me to get back in the ring?”

“Even better,” he smiled. “Perfect timing for a knight’s move.”

That night I didn’t sleep. I replayed every report, every press of save. Then I understood: I’d been framed. And I knew how.

In the morning, I dug through old emails. There it was: an internal draft that should never have made the final report — yet there it sat, carrying my signature. A signature I had never placed.

A scan–cut–paste job. And only one person had both the skill and the ice-cold heart to do it.

“I’m in,” I called Nikolai. “And I’ve got something.”

“Good,” he said without asking what. “Once we start, there’s no turning back.”

“I don’t want to go back,” I said. “I want to go forward.”

Ready… set… revenge

Next morning I buttoned a dark jacket and entered a new tower. Nikolai’s construction firm smelled of ambition, coffee, and a hint of cinnamon.

“So she didn’t forge your signature — she copied it?” Nikolai twirled a flash drive like a grenade pin.

“Scan, vector, PDF — pick your poison,” I shrugged. “You don’t know what a woman who despises her daughter-in-law can do.”

“I lived with her twenty years,” he chuckled. “I left my hair and nerves behind. You lasted longer than I thought — four years?”

“Five and a half,” I corrected. Each memory — dinners salted with innuendo, looks sharp as knives — made me want not only to strike back, but to do it beautifully.

He made me deputy of finance despite the scarlet stamp “terminated for cause.”

“I wanted Dima to marry a smart woman,” he said. “Didn’t realize intelligence would be contraband there.”

“Want me to play dumb?” I slanted a smile. “Like Tanya — carries coffee, laughs on cue.”

“You’re too independent,” he said. “Alla doesn’t like independent. She likes convenient — nodding, agreeable, adoring.”

“Oh, I can adore,” I leaned back, “especially if the person I adore is holding a Mercedes check with my name on it.”

He laughed out loud.

A week later the laughter stopped. He slid over a stack: emails, transfers, ledgers I’d never seen at the old firm. The signature copy was only the tip: Alla was siphoning funds. Not millions — tens.

“See?” he tapped a sheet bristling with tables.

“Offshores,” I frowned.

“And that would’ve been your express ticket to hell if you’d stayed,” he said mildly. “Now you’re a witness, a victim. Or — if willing — a co-author of my little plan.”

“I’m already in,” I said. “This isn’t theater. It’s a criminal case.”

The plan: expose — loudly, theatrically. I would walk back into Alla’s office not as the shamed ex-employee but as the woman with documents, a lawyer, and ideally cameras.

But first: irrefutable proof.

“I have an idea,” I said from his top floor. “I need the old archive. Originals. Drafts. She hoards them like a dragon hoards relics.”

“Serious?” He arched a brow. “Risky.”

“Has anything with you felt safe?” I smiled.

On the day, I went in disguised: long coat, ponytail, quiet frames. The guard — the one who’d shared lunches — squinted:

“Marina Sergeyevna? Who are you here to see?”

“Legal department. Personal matter.”

Not a lie. Very personal.

While they rang Legal, I drifted deeper. Same coffee smell. Paper rustle. Someone cursing at Excel behind a partition. Door: “Finance.” I tugged. Locked. But I still had the key — “forgot” to return it.

Five minutes. I rifled a drawer. Found a gray folder. Inside: documents edited after my dismissal, carrying my e-signature.

Look at that, sweetheart — I’m useful even when gone?

When I placed the proof on Nikolai’s desk, I said only: “We go to the police. Bring in counsel. It’s criminal.”

“Ready for the scandal?”

I rubbed the bridge of my nose. “Can’t wait to hear how Alla explains authorizing a transfer to Switzerland while she was in the hospital with a 39-degree fever on IV. I have the certificate. And witnesses.”

That night Dima called.

“What are you doing?” he hissed. “Mom’s hysterical. Says you declared war.”

“War?” I snorted. “She declared it when you two decided I was disposable.”

“You’ll destroy everything,” he shouted. “Family! Company! Money!”

“Family is where there’s no betrayal,” I said quietly. “Your family is wherever your mother is. Mine is wherever I’m respected.”

“She says you and Dad colluded. You staged this to get revenge.”

“Dima,” I said evenly, “if I wanted revenge, I’d show up with a frying pan. I’m restoring justice.”

He faltered, then sneered: “You’re nothing without us. Just an ex-wife.”

I smiled. “And you’re just your mother’s son.”

Flipping the table

A summons arrived: court. I was listed as witness and victim in a major fraud case.

Three months later, they detained Alla. In her office. Under the gaze of her own framed portrait.

That evening Nikolai brought wine — and an offer.

“Marina,” he poured, “stay. Not as deputy. As partner. Equity. Properly.”

I looked up, feeling something words can’t hold — like being thrown off a moving train and waking in a luxury carriage with champagne in hand.

“Promise me one thing,” I clinked his glass. “I never want to see ‘made-up’ reports again. If I do, I’ll throw them at you.”

“Deal,” he grinned. “You’re dangerous.”

“No, Nikolai Petrovich. I’ve just stopped being convenient.”

The next two months, the company rocketed. Equity papers signed, new office, and the headaches power breeds.

Alla waited for trial, banned from management. In our small business circle, to fall into muck is to set in concrete — it doesn’t wash off.

When the noise faded, silence came. Not sobbing, not yelling — a ringing emptiness.

“You know the worst part?” I asked one evening, watching my wine. “Winning and feeling… nothing.”

“So you’re not happy?”

“Happiness is the blanket, a light fever, and potato pies,” I smiled. “This is like winning the Olympics and the stadium is empty.”

He sat with it. “I’m alone too. Five years. The house is a museum — beautiful, empty.”

“We’re two exhibits behind glass,” I sighed. “My price tag fell off long ago.”

“You’re no exhibit. You’re a woman who walked through fire and kept her spine.”

“How old are you?”

“Fifty-nine.”

“Then there’s still time to build more, plant a tree, get divorced three more times,” I teased.

“And…” he paused, “to marry again. A clever woman who hates stupidity and loves cinnamon coffee. You dreamed of that, didn’t you?”

I studied him like a hard equation. “On conditions: no white dress. And separate bathrooms.”

The office began to whisper. Someone “saw” us at lunch. Someone “heard” him call me “Mashenka” — even though he always said, “Comrade Partner.”

Dima called once, voice crumpled like an old letter: “Mom says… you and Dad live together?”

“Tell your mom we already share a bed,” I said pleasantly. “Orthopedic mattress. Healthy spine — key to success.”

“He’s getting back at her, right?”

“He gets back at her by not regretting the divorce.”

“You like that?”

“No, Dima. I’m just living. For the first time.”

The hearing — and one clean answer

On the day, the courtroom overflowed. Alla — stiff suit, lawyer, chin high, face of ice. She didn’t look at me.

I was collected, steady. A folder, a lawyer, and a deep inner stillness. No rage, no vengeance — just facts. My decision had been made long ago.

My testimony was brief:

“Yes, I was dismissed on falsified documents. And yes, I forgave. But forgiveness doesn’t erase responsibility. Especially when you’re a director. And a mother.”

Verdict: four years’ probation and a ban from management. Only then did Alla look at me.

“Do you think you’ve won?” she asked softly.

I smiled. “I don’t think. I’m simply not afraid anymore.”

That evening, outside the courthouse, Nikolai waited in a suit, a bouquet in hand, a shy smile at his lips.

“For you,” he said. “For courage. And for not becoming her.”

“I almost did,” I admitted, taking the flowers. “You pulled me out.”

“Then let me offer not a date,” he said, holding out his hand, “but a life. Quiet. No intrigues. Chess and morning coffee.”

I met his gaze. “Deal — if at home I may wear a robe, curlers, and bear socks, and you don’t run.”

“I’ll stay,” he said. “Even if you curse sausage packaging.”

I laughed. “All right. No schemes, no setups. Next time it’s you in detention.”

Summer begins

That summer I went south. No husband. No laptop. Just myself.

By the sea, sipping wine, I remembered the day I thought I’d forgotten how to laugh.

I’d been wrong.

Life starts over. At forty-eight.

Especially when the person beside you isn’t afraid of your strength.

That evening back in Moscow, I kicked my heels into the corner and flopped onto the sofa without taking off my jacket. Vasya the cat flicked his tail; a bottle of sparkling nudged my elbow.

“Can you believe it, Vasya?” I said to… the kitchen cabinet. “They accused me of embezzlement in front of the whole room. Me — the one Grand Consult audited. Hilarious.”

No answer. Cabinets keep secrets better than people.

I leaned back and laughed. This time it wasn’t bitter. Relief has a sound — light as the fizz in a flute.

And somewhere, in a quiet apartment of a fifty-nine-year-old man, a coffee machine hummed cinnamon into the air. My new morning had begun.