Dana pressed her palm into her belly. The child inside moved like someone testing weather.

“What is Grayson doing?” Dana asked.

Sophie’s jaw tightened. “He buys them cheap. He keeps them in a tobacco barn at the edge of his north field. He isolates them. Then the women disappear. Some say they die in childbirth. Some say they run away. None are seen again. Infants cry at night from that place once in a while, and then no more.”

“Why buy infants?” Dana’s voice was a hoarse whisper. The thought of Rose sold away had hollowed out something in her like a well. She listened now as if each word could thread a rope.

“Because he can,” Hailey said. “Because law calls you property. Because he knows powerful men will look the other way.”

Jackson’s jaw set. “And because people like Grayson benefit from the system. They profit from disposability. We—some of us—decide we will not let him have any more victims.”

The cabin became a place of quiet operations: mending shirts and mending a life. Dana slept in a bed with real covers for the first time in years. She ate, and smoked like someone who had been granted a rare liberty: to eat and not be served while someone watched. For three days she let herself feel nourishment as a small act of treason against what had been done to her.

Then the news came back: Grayson was asking questions in Savannah, showing Jackson’s face at taverns, offering silver for information. Jackson had to move quickly. The plan shifted. The Underground Railroad—wordless as it was, a braid of hands and hides and voices—offered a sea route north. A sympathetic captain in Savannah would hide Dana in a crate behind the hold and carry her to Wilmington. From Wilmington, Thomas Garner’s network would carry her by night through Pennsylvania and out to Canada.

“You will travel by sea,” Jackson said as he fitted a small purse of money into Dana’s hands. “It’s dangerous, but it will bypass men who watch roads.”

“Will you go with me?” she asked. The question was not simple. Jackson had offered her something more than safe passage—he had thrown down his coin like a gauntlet at the auction to deny Grayson his prize—but he would be, in their parlance, a signal to those who hunted him.

“No,” he said, and his voice held no apology. “If they know Jackson Marsh is here, they will hunt Jackson Marsh. I will disappear. You will not be traveling with me. You will be traveling with those I trust. I will be a ghost. That is enough.”

The night they crept onto the ship, the docks were a dark machine of ropes and men and the sharp scent of tar. Captain Sam Porter was a man with a gull’s face and a weathered hand. He kept his promise in the way he could: a crate behind the hold, food here and there, a strict word to make no noise. Dana crawled into the small space and folded herself to fit like someone learning a new and deadly shape. The wooden boards held the damp smell of fish and salt and other things the cold ocean carries.

The voyage began with an ache of relief and ended, three days in, in weather that sounded like a hymn of the sea and a wrathful litany in equal measures. Storms come like judgments and like chances both. The ship pitched. Planks shifted. Dana held herself closed around that strip of future as the world roared. Minutes became lifetimes. For two nights and a day the deck lost its rhythm and men stood by with ropes and with hands that were only sometimes kind. When the storm piped down to a long, exhausted moan, Jackson’s plan began to unravel.

Michael was twenty-three and had the sort of quiet that comes from loss and simple, stubborn hope. He had watched Ella quietly; sometimes he helped her carry things or translated a phrase of German when she stumbled. He had lost a brother to the Pacific theater and, as was the way of sons who come home from war with emptiness, he felt dislocated from a life he had never really left.

Whitmore asked him: “How would you like to do a good thing?”

Michael looked at the captain as if the man had asked him to lift a barn. “What do you mean?” he asked.

“To marry her. On paper. For immigration. For a life she could not otherwise have.”

The pause between heartbeats carries the whole of the world in it. Michael had been lonely in ways that sounded at first like boredom and then, under the captain’s words, like the possibility of purpose. He thought of his parents in Iowa, steady and full of grange meetings and Sunday suppers. He imagined going home and having in his pocket the knowledge that he had smoothed the course of one human life.

“I’ll do it,” he said. He said it in the way that farmers speak about winter: a practical decision that contains within it a kernel of prayer.

They married in a small church in Grossenbach on a gray afternoon. There were no flowers worth mentioning and the priest read the liturgy with the careful cadence of a man who has learned to fold human complexities into ritual so that life may continue. Michael said his vows in German, halting and honest. Ella said hers in English, each syllable an act of faith. Captain Whitmore and Schmidt stood as witnesses like pillars of an unconventional temple. It was not a grand event; it was a plea for mercy given shape by ink and signatures.

The paperwork began as if bureaucracy itself were a stubborn river. The status changed. Ella became a dependent of Private Michael Carter. She was given a place in the ledger, an entry in the machine that decides who may step across an ocean and who must remain behind. Months passed and the waiting had the quality of a test. The women she shared a boarding house with—other Germans who had married American soldiers—became her allies and friends. They studied English together with an intensity that felt like something between hunger and worship. They taught each other to bake what they could not buy, to laugh small and brittle laughter, to fold hope into the dullness of everyday tasks.

On a gray day in April 1946, in the small harbor of Bremerhaven, Ella stood among women who carried their pasts in bundles and their present in the way they held their breath. The ocean was large and indifferent. The Statue of Liberty rose through the mist as if it had been waiting for people like Ella her whole life. At Ellis Island, the corridor was a blur of questions and stamps and the hum of names slotted into new identities. At the train station in Des Moines, Michael stood with his parents, broad and polite and with that Midwestern reserve that manages to be kind even when it is surprised. He took her single suitcase and welcomed her to a country that was at once alien and kind.

The Carter farm was white and smelled of fresh hay and the strange, deep clean of a place that had not yet been ground under the machinery of the new America. Michael’s mother, Evelyn, took Ella into her arms and did what mothers do best: made a room and made a place at the table. She taught Ella to cook cornbread and to sing in the church choir she had never known would be a whole new grammar of belonging.

At first, Ella was an outsider whose language was measured and whose taste in humor lagged behind. She missed the small things—her mother’s seamed hands, the sound of the half-remembered songs they used to sing while shelling peas. But the Carters were patient in their practical tenderness. Michael took her to town and introduced her to places and faces. He showed her how to set a fence post and how to name the sky. She taught him, without sermon, about endurance and the economy of loss.

They were married on paper at first, and then, in the slow, undeniable way that seasons take root, they married in truth. The young legal fiction became an old and steady partnership. Love, when it arrived for them, was not a single flash but a hundred small confirmations: the way Michael learned to take her hand when she woke in the night from a nightmare; the way Ella learned to make his favorite coffee in the mornings; the soft, unexpected laughter that began to show itself in their kitchen.

In 1856, a Quaker missionary in South Carolina answered: a girl worked on a small farm a few miles outside Charleston, a girl with eyes that remembered a cradle that had been a kitchen. The letter had to pass through countless hands and prayers, but it came at last into Dana’s lap like a small coal still warm.

She decided to go back. Samuel Rivers—her husband now, a blacksmith of patient hands and a steady laugh—was frightened. He should have been. Going south as a woman who had escaped was like walking across a field of fevers that could name you at any gate. But Samuel was not a man to chain the heart of a woman who had already set hers on a small rescue. He tightened the leather of his gloves and said he would come as far as he could and then return if need be.

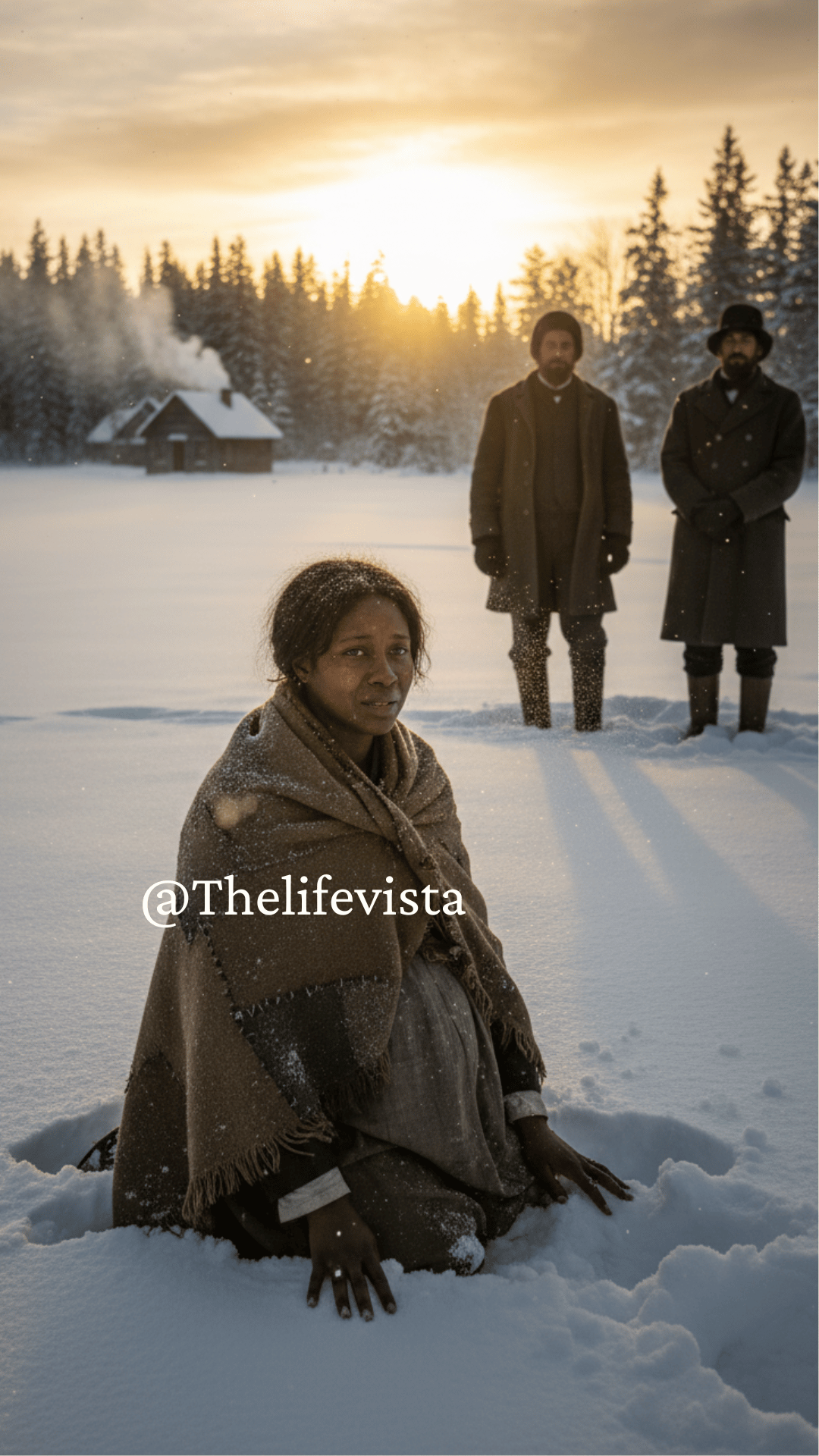

They traveled with two conductors, men who had guided dozens of fugitives north and who had known the meaning of hiding. South was a different winter—tangled roads, tighter suspicion—and they had to walk a careful line along the edges of fields and through the darkest places of people’s sympathy. At midnight under a moon that wavered like a god’s half-face, they found Rose sleeping in a cabin with three other girls. She was now thirteen: the same eyes, the same lightness to the skin, the same small, stubborn chin.

Dana woke the girl like a woman returning to a home she had been forced to leave. “Rose,” she said softly, “I am your mother.”

Rose blinked like the world had been turned sideways. For a long minute the two of them held each other in silence that was full, enormous, as if some small universe had shifted and let the two of them become whole. The theft of years could not be undone, but then neither could it be entirely repaired. They moved quickly, hiding beneath leaves and stars, until Dawn and Canada and Jackson’s small hands awaited.

Reunion did not erase trauma. But it made the missing piece visible enough to hold. Rose learned to play with Jackson and to listen to the long stories of her mother. Dana taught her to sew the old marks into linings and corners: the bird in flight, the map of secret kindness.

Years passed. Dana watched her children grow—Jackson strong and stubborn and fast to laugh, two daughters who learned to read and to reason and to refuse the easy narratives the world offered. She taught them to value the ledger of human dignity more than the ledger that had once kept her as cattle. She told them about the people who had helped her: Bethy who had risked a silence for the sake of dignity; Jackson Brennan who had been both the stranger and the friend who paid the sum to deny a monster his prey; Sophie and Hailey with their simple cabin of beans; Captain Sam Porter who had paid for his kindness with death at sea; Mike the sailor who, angry at injustice because his own father had been eaten by disposability, kept a promise; Thomas Garner who had turned words into safe hands; Frederick Douglas who had told her to speak; and Samuel Rivers, her husband, a man who had shaped a hammer to make this life possible.

Dawn grew, too. It became more than a settlement: a small town of schools and workshops and places for those who had been stripped to take back their names. People from many places found each other there—escaped men who later fought in the Civil War, women who taught children to read, men who farmed the land that had once taught them their enslavement. Dana taught in the little school and sewed long into the nights. She wrote in a small journal, careful and steady. The ledger of her life she turned into witness: to name what had been done and to keep the names alive so they would not be erased.

The story of Thornton Grayson did not end in a public gallows. The country had other urgencies and a war that turned its own infernos into a different reckoning. Grayson fled as Union lines advanced, his property abandoned. Men with histories of slavery and men with histories of escape both combed through the plundered barns and found things no law had been meant to find. Sergeant Isaiah Freeman, an escaped man who had chosen the army and who carried the memory of a life he had refused to relinquish, pried up a floorboard in a tobacco barn and found a cellar: bones wrapped in canvas and the faint echo of a life erased. Captain Henry Clark documented the testimony but the war swallowed the rest for the time being.

The bones were there; the testimony was muffled by the noise of a country tearing itself apart and then attempting to build itself anew. The Grayson family tried to silence the revelation later on; power has a way of trimming histories like hedges. But the memory refuses to be fully fenced. Patricia Whitman, a graduate student a generation later, dug through the military files and found the report locked in dew and ink. She nearly published. She was stopped with the old and furious methods: the law used not to scorn truth but to bury it under threats and money. She put the report in a sealed envelope for fifty years, like a neat and angry time capsule, and it slept until a modern world had different lights.

Dana lived long enough to see men like Elias Carter die bankrupt and alone and to see some of the layers of the law come apart for others. She lived long enough to know that not everything is justice, and yet some things are. She taught her children to write their names not as ownership but as claim. On the last page of her long-jotted journal she wrote, in a hand that had learned to hold a pen with the same dignity it had once used to scrub pots, these words:

“I was sold for nineteen cents because a man wanted me to feel worthless. I was never worthless. No human being is. We are witness, we are witnesses, we must be. Remember the women who were buried in secret. Remember the men who helped. Remember we are not a ledger to be balanced by others. I ask you to keep the names, to tell them aloud. This is how a people neither kneel nor forget.”

When she died in Dawn, surrounded by the children and grandchildren she had built like small cathedrals of endurance, the town came out to bury her. The sky did not thunder; there was no prodigy. There was only the honest plodding of a community that had formed itself against a system that had made them debtors of pain. They placed her in a grave without ledger and without auction marks. Children called out names across fields the way that other people might shout glory from balconies. They planted flowering bushes near the headstone because someone had read somewhere that plants forgive the earth if we let them.

Years later, when Patricia Whitman’s envelope finally found a public light and when historians held the old, yellowed report in their hands and read aloud the names that had been unnamed for so long, Dana’s journal was among the few voices that knew the secret connections. In those pages were the routes, the tiny bird mark, and the names of people who had dared to pay more than money. They were small acts piled into a mountain.

The country argued about memory and monuments and what to do with the bones and with the documents. In some corners, the silence held fast. In others, the bones were reburied with a simple marker that read, Victims of slavery, 1843–1862. May they rest in peace. It was not nearly enough. It could not be. But it sang, in a small, imperfect voice, the truth that a grave, even when unmarked, was not invisible to those who refuse to forget.

In Dawn, they taught the children a different ledger. They read Dana’s journal aloud in the winter, and they painted the tiny bird that had saved a woman’s life here and there on quilts and doorframes. They taught the boys to hammer not to make chains but to build plows. They taught the girls to read the names that might have been taken from them and to claim them back by memory and by voice.

Dana’s last son, Jackson, grew and had sons of his own. He learned with patience and rage the craft of telling. He called his children by names that would not fit easily onto any sale ledger. He passed down the scrap of paper Jackson Brennan had once given his mother—the folded purse of money, the map of kindness. He kept the secret marks where they would not be sold but where they would be gifted to those who needed them: a woman with a newborn at a train platform, a man with a satchel who would be disappearing, a child who could not read the way the sun carved shadows on the ground.

The thread of Dana’s life ran wide and thin: a woman bought for nineteen cents, a ledger of cruelty that somebody tried to make simple, and then the beautiful, messy complexity of people who say no to the bargain. Her story did not end with a triumphant headline. It ended with small days and small acts: mending, teaching, telling, returning for a daughter, burying a mother’s grief in the flint of a neighbor’s hands. It ended with her insistence that names be known.

If you ask who saved Dana, the answer cannot be a single face. It is a long chain of hands: Bethy’s quiet courage, Jackson Brennan’s reckless coin, Sophie’s cabin and its beans, Captain Sam Porter’s kindness and death, Mike’s promise, Thomas Garner’s roads and his careful eyes, Frederick Douglas’s voice, Samuel Rivers’s steady hammer. They were not saints of parable; they were human beings who made the hard choice that some things are never worth selling. They were the ones who understood that the law can be a ledger of injustice—and that people can be pockets of revolt within the law’s margins.

Dana’s last page lists a small vow: Remember. She asked also for a small kindness from those who would read. “Tell Rose I looked for her always,” she had written as a line that trembled. “Tell Jackson to grow strong. Tell them we were not worthless.”

They told the story in clusters—at first in Dawn around wood fires, then in town halls, then finally in archives, and people who read the dry reports found the bird and recognized what it meant. The thirteen-year-old who had slept in a stranger’s cabin in a South Carolina night heard her mother’s voice again and learned it to be strong.

History is always an argument with itself. It denies and embraces, hides and reveals. But there are small certainties: that Dana lived beyond the price they wrote on paper; that she taught her children names that could not be owned; that someone somewhere made the choice to spend far more than money on a life—and that the ledger of humanity was richer for it.