The words landed with a clarity that stilled him. He moved in three strides, closing the distance until his bulk eclipsed the younger woman. Her eyes were cold and old in a way that made his belly tighten; he had seen that look before in men who’d survived the worst.

“You don’t know anything about my world,” he said softly.

“Don’t I?” she shot back. The heat in her voice was quiet, controlled. “Your enemies know she is blind. They know she’s isolated. How long will it be before someone decides she’s the way to hurt you?”

He could have told himself he had security in layers: hired men, quiet bribes, coded favors. But Sarah spoke a kind of truth that money could not buy: guards could be bought; they could be corrupted, turned, neutralized. A woman who could defend herself was something no one could take away.

Jonah’s anger—always the first thing he felt—shrank back under a deeper current: fear. He told her to leave. Sarah looked at him for one long moment, then nodded and put her baton on a shelf. “Your daughter is stronger than you know,” she said quietly. “The question is whether you’re brave enough to let her prove it.”

After she left, Jonah sat at his desk in the study and poured whiskey until it burned the place where sleep should have settled. Photographs of himself with men he’d made—some dead, some now far away—looked down at him, civic trophies of a life built on fear. In a frame, Lucy smiled in a way he could not remember teaching her to. He thought about the concept of strength: his kind, his father’s kind, the kind that took and never gave back. He hid his weakness in contracts and port negotiations and moving men like chess pieces. He had never asked where the money came from, only that it had come.

Tom—his consigliere, old as the house and sharper—arrived without knocking. He did not pour whiskey. “You fired the maid,” Tom said, settling on the chair opposite. He’d known. He knew everything. “Don’t be an idiot, Jonah,” Tom added, “she’s been teaching Lucy for weeks.”

“Teaching her to fight? With wooden batons?” Jonah scoffed, but there was a hollow in his own voice. Tom’s eyes, the color of bad weather, did not flinch. “You remember Peter DeLuca’s son, don’t you?” He did. He saw the headlines: the boy in a wheelchair, snatched, returned—pieces of a life gone. Jonah’s chest tightened; he had made enemies who would take vengeance through children in their reach.

“Your daughter is your heir,” Tom said. “One day she’ll be the one in charge. What then? Will they respect the family if they see weakness?”

Jonah thought of the mansion as a fortress; he had built it that way. He had padded corners, ordered the roads moved, paid for security systems that ran like clockwork. But to Tom, and perhaps to experience, that was a brittle thing. He could lock Lucy in, pad her life with music and men, but anyone with the will could find a way through.

When Lucy slipped into the study a heartbeat later, as if she had been listening at the door, Jonah found himself saying the thing he’d meant to guard against. “You can keep training,” he admitted at last, because he could see the hunger in her face. “But under conditions. I supervise. If I think you’re in danger, it stops.”

She smiled like sunrise. “Thank you, Papa,” she said.

Two days later Jonah visited a gym that smelled of liniment and old sweat in a neighborhood his suits had never needed to know. He left his bodyguards outside; this was not a question for muscle. The gym was a basement room under a peeling sign, and in a corner an old man whose one eye was cataracted and the other merciless showed Jonah a photograph: a young woman in torn shorts, a blood-splattered grin, the crowd roaring around her. The White Wolf, they’d called her—undefeated in forty-seven fights, a creature of forged muscle and will. That was Sarah.

The old man told the story in fragments: her brother Luca, sick and needing a surgery in Switzerland; the ugly tournament in the port district where men gambled on pain; the match where they had placed Luca in the ring as leverage. Sarah had tried to throw the fight and failed. Her brother had been beaten to death in the crowd while she fought on the floor. She had disappeared into a grief that never ceased being a wound.

Jonah had paid for that tournament, then as a young man, signing a paper that made his father richer and everyone else lesser. The old man’s words slipped into the cracks of memory and burned. Jonah had not wanted to know where some of the money came from; he had taken it like a man had his inheritance, never asking how it was stained.

When he returned home the answer to the question he’d been avoiding—what to do with Sarah—arrived with the certainty of a reckoning. He could not erase what had been done, but he could choose according to what he had become. Lucy had asked to be seen as more than frailty. The sight of his daughter moving with something between defiance and calmness made the choice for him. “Fine,” he said. “Keep teaching.”

Sarah nodded once, and finally Jonah slept.

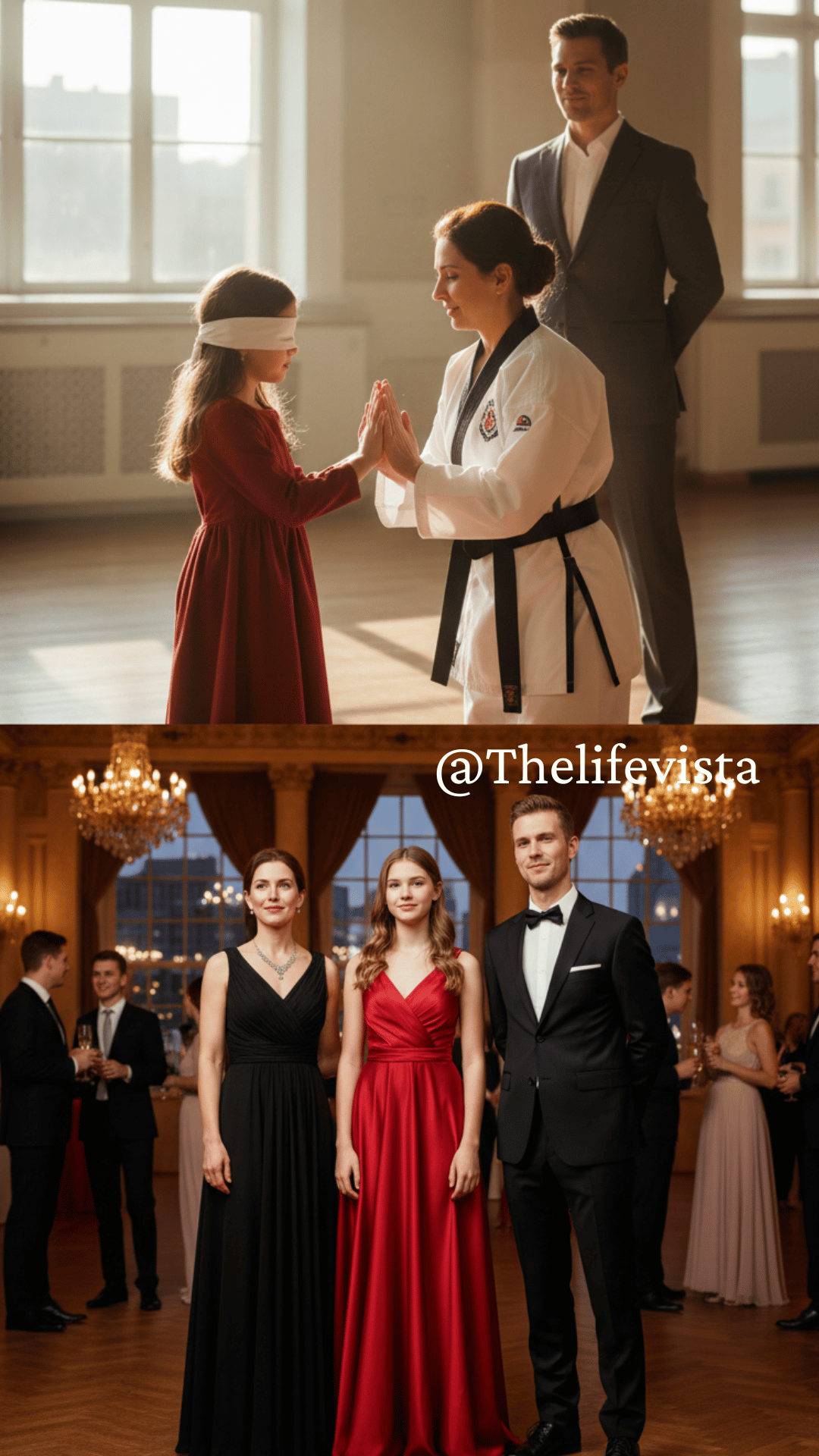

Training began in earnest. Sarah’s methods were brutal in their simplicity: teach Lucy to hear beyond sound. Bells were hung at varying heights over a winding path strewn with tempered glass; the glass would crunch without cutting if she stepped on it, a noise punishment to be learned. The bells would chime the location of stakes. Sarah taught Lucy that sound was a landscape and that with practice she could map it.

The first few attempts were a litany of errors and exactly the kind of failure that would change a life. Lucy rang more bells than she avoided, stepped on glass, flinched, wiped blood that wasn’t there—the sound hurt like punishment. But she also laughed between runs, a thin, determined sound. On the twentieth attempt, she stopped and made a soft clicking noise with her tongue—echolocation—one Sarah encouraged. The bell’s echoes then became shadows made of noise, and for the first time, Lucy walked the path without ringing a single chime.

Word travels in their world. A servant mentions something at a dockside bar; a cousin overhears; a runner passes it along. Every whisper is a scent on the wind. Within days the rumor of a blind girl training with the White Wolf at the Westfield estate reached a dozen ears in the syndicate houses. The information took on a life of its own, distorted by fear and imagined motives. To some, it looked like preparation. To others, an insult. To all, it was an opportunity: if Lucy could be turned into a liability, her father could be broken.

An emissary arrived on a rain-slicked Thursday evening, a man of forgettable face who carried an envelope that sat like a lump of coal on the marble hall table. He offered Jonah a “civilized” way to prevent war: a tournament challenge for disputed territory, single combat champion versus champion, first blood or submission. It was the oldest parlor trick in their world: force the family to commit and thereby provide spectacle to the hungry, while positioning men to make real decisions behind the scenes.

Tom watched the emissary like a snake watches prey. Jonah felt the trap armored in ceremony. If he accepted, the tournament would be on neutral ground—an arena ten years older than the scars still within Jonah’s chest. If he refused, there would be no pretense and they would come for his daughter in the night. He accepted; it was the lesser madness.

He did not tell Lucy the whole truth. He told her there would be a fight, a father’s duty to answer a challenge. She understood. She asked to be the one to be trained. Sarah looked up when Jonah asked whether she would fight in his place. She did not answer at once. In the solitude of her room that night, she told Lucy the story of Luca and the terrible pragmatic failure of the past—a sister who could not save her boy. “I taught him to be strong,” Sarah said. “I should have taught him to be smart. Strength without strategy is suicide.”

Lucy listened and, gently as a bell, offered a promise. “If I train,” she said, “I won’t be a burden anymore.” Sarah placed her hand on the girl’s cheek. “Promise me,” she said. “Promise me you won’t confuse being strong with being willing to die.” Lucy promised.

Sarah told Jonah with blunt honesty: eight days. Maybe. It was not time for sentimentality. Jonah’s son-of-suit instincts—strategize, arm, plan—fought with his father’s instincts—keep the child unscarred. He arranged for Tom to coordinate surveillance and increased perimeter details. But as the city watched and the syndicate whispers grew teeth, their world narrowed to an arena.

On the seventh night a storm arrived like a curtain being torn down. Sarah led Lucy to the roof at midnight: the final test. Rain hammered like a thousand tiny fists; thunder cleaved the sky. The rooftop offered no echoes to click against; the storm swallowed sound as if it were ash. Sarah left Lucy alone and vanished into the noise. “Find me,” she called.

Lucy found the variation in the rain: a different beat, a human warmth moving through cold. Training had been about more than batons and drills; it had taught her to feel motion in the air, to sense the small trauma of a passing body. Attackers—Tom’s suggested guard volunteers—came from four directions. Lucy moved the way a person with no sight but full body memory can move: through listening, through intuition, through the small thrum of muscle memory. She avoided blades and struck nerve clusters, rolled on the wet rubber mats, and when one training partner pressed her against the low wall at the roofline she twisted his wrist into a lock she had practiced a thousand times and the baton slid from his hand.

Sarah watched rain stream from Lucy’s hair and smiled—the first true smile Jonah saw from her since the woman had arrived.

The tournament night came with a pretense that fit a decade of ritual. The underground coliseum smelled of rust and old blood. Syndicate bosses sat in the private boxes as if waiting for offerings. Jonah, Lucy, Sarah, Tom, and the tight ring of men who would not die for them walked into the belly of it like a small armored unit. The light and noise of the arena drew a tide of faces—rich and brutal and ordinary—curious—and in the tunnel of the competitor’s holding room, Jonah felt the premonition swell again.

Then everything went dark.

It didn’t go dark like a power cut. It went dark like an answer to a prayer: lightning snapped and the lights died, then emergency floods set the world into blinding white. Men with night-vision goggles poured through the cracked doors with military discipline. It was a siege. Jonah turned on reflex, gun hot in hand. But before he could make any move a shape lunged at him from the side and Lucy stepped between them, lightning-fast for a child, catching the wrist of a man with a knife and twisting him into submission with a joint-lock they’d practiced on the roof under a bad sky.

Sarah became storm, a flint of blades in perfect rhythm—no wasted movement, no rage, only economy. She took down three attackers while Jonah and Tom and others returned fire. The ambush unrolled into a public theater that had gone wrong for the attackers. The unknown man in the syndicate box barked orders, and then, just as it seemed the night would become a bloodbath, the tunnel behind them filled with blue-uniformed officers and men in armored vests. Tom walked forward, phone out, and the camera on his hand had caught the attackers’ faces and every illegal plan in the box. The authorities had been waiting for just that. It was a sting disguised as treachery; Tom had gambled and the house had fallen.

In the stunned silence a thing occurred to Jonah like sunrise: all of the careful strategizing, the favors, the contracts—had been to hide hurt. Tom smiled a thin smile. “You could have refused the challenge,” he said, “and they would have come for you anyway. I made a deal with the feds. We used your enemies’ arrogance against them.”

They came. They were arrested. Syndicate heads sat in handcuffs as reporters pushed mics into faces. In the middle of the arena, Lucy stood breathless but alive, the rain of the storm clinging to her lashes as if the sky itself went easy. Sarah approached and for the first time Jonah saw her honest face without the mask his suspicion had applied: grief, relief, and a woven something like hope.

“Stay,” Jonah said to Sarah—not as a maid, not as the woman he had once thought of as a worker. “Stay as Lucy’s teacher. Stay as family.”

Sarah looked at him like she was weighing a world he could not see. “Your father’s money killed my brother,” she said before she could be anything else. The truth was a clean cut that left them all bleeding. “I came here to make you suffer the way I had suffered, but I saw your daughter. She reminded me of Luca. I can’t bring Luca back. I can try to make sure Lucy never becomes a casualty.”

She knelt before Lucy. “I will be your master,” she said at last. “Not your maid.”

Lucy hung on Sarah like a lifeline. The White Wolf—Sarah’s old nickname, reputed and feared—wrapped in grief and ruined nights, had offered the heater of her skill to a girl who had once been merely a liability. The transfer of that which is dangerous into that which is necessary felt like something older than vengeance. It was a choice.

In the aftermath the city hummed. Footage of a blind girl standing calm in the center of a ring of gunmen spread like a fever across phone screens and television panels. Men who had assumed the girl was an easy mark saw in her something else. Mothers who watched with their children felt their throats tighten. Underground bookmakers recalculated their bets.

Three months later Lucy stood on a public stage, the same girl who once had been told to avoid the world. Fifty people watched: clients, a few old faces from the syndicate boxes released on bail or in cuffs, and journalists waiting to shape a narrative. Sarah stood behind her, hands folded. Jonah sat at a table in the back, a presence that was both fortress and apology.

Lucy moved through combat forms with a grace that left the crowd silent—silent in the way a room holds breath at beauty. She disarmed three opponents, navigated an obstacle course designed to punish those without sight, moved like someone whose darkness had been taught to speak. At the end she stood in the middle of the floor and said, to a microphone and to the cameras and to the men who had once thought to use her as a weapon against her father, five words that would become a kind of quiet legend.

“I don’t need to see you.”

Those words were not a taunt. They were a decree. They meant that the world could no longer impose on her a definition of helplessness. It meant that a father who had hoarded control could now give it up. It meant that a woman who had lived with the weight of an unchosen decision could choose to reforge it into shelter.

Life after the arena was not an idyll. There were long nights when Jonah could not stop seeing the smear of his father’s bank statements, the signatures that marked the moment the money turned to blood. The Westfield name was crooked with old sins and new sacrifices. Tom used the arrests to pivot the family into a different kind of bargaining. They had bought a kind of immunity, but not absolution.

Sarah kept teaching. She refined Lucy’s skills into a discipline that was more than combat: timing, patience, the wisdom to know when to use force and when to fade into the background. She taught Lucy to read an air current like a map and to find a voice among a thousand noises. Lucy learned to be still in a world that prized motion, and in stillness she found a reservoir not of fear but of choice.

Jonah became a softer man in small, honest ways. He still made deals; he still moved men through contracts and cargo. But he started to call Lucy to meetings in his office, to ask her opinion on matters he thought not fit for a child. She listened to logistics, to the language of risk, and then would speak, in her measured, surprising voice. He began to see that protection was sometimes an act of releasing—not hiding. One night when Lucy arrived late from a demonstration and he opened the door to find her with Sarah and a tutor who taught law to youths, Jonah realized he had stopped worrying about where she was. He instead worried about who she would become.

Lucy did not become a commander of syndicates. She did not become the brutal force the whisperers had predicted. She became something more complicated: a person who could move through darkness with precision, a woman whose reputation protected her family not by terror but by respect. People in the city recalibrated their images of power; it no longer meant the ability to crush, but could mean the ability to cultivate.

There were small kindnesses that sustained them. Jonah would bring Lucy home tea and sit with her while she read Braille and tell stories about his own childhood without the sugar of romanticization. Sarah took walks with Lucy through streets where light pooled and taught her to listen to the city’s pulse: the echo of a tram, a barrel vendor’s call, the cadence of a crowd. Lucy taught Sarah to let things go—tiny things, like the smell of Luca’s old jacket or the memory of a ring where hands had been red.

Sometimes, late at night, the three of them—father, daughter, teacher—would sit on the mansion balcony and watch the poor wash of the city lights. Jonah would speak quietly about mistakes he could not remedy. Sarah would speak of her brother in the present tense as if he listened from another room. Lucy would listen and then, as if arranging music out of memory, click a soft rhythm and explain what she’d heard in the noise of the night: a stray dog, two windows opening, a bike wheel. The house felt like a small world in which there was action and healing and not all debts found ledgered closure. It was not neat, and it was not polished, and sometimes the past reached up and bit them. But they had one another.

Months turned into the sort of seasons that change people from the inside out. The Westfield name remained—some men never changed the things they had. But under it, a different root grew: a lineage shaped not only by the hunger for more but by the tempering of what cannot be repaid. Jonah stopped walking like a man who feared his own shadow; he began to walk like a man who had been taught how to carry a lighter load.

One evening a woman from the old neighborhood—the gym with the one-eyed man—arrived at the estate with a small bundle of flowers. She had a boy on her hip who had the same slow heart and sharp smile that had once been Luca’s. Sarah went out to meet her on the steps. Their conversation was long and quiet. When they came back inside, Sarah placed the boy into Jonah’s hands for a moment. The child fell asleep in his arms, the even breathing of someone safe and simple. Jonah felt the soft guide of new responsibility like a balm. He did not try to undo the past. He held the present.

Power had taught Jonah to solve problems with contracts and weapons. Fatherhood taught him something else: the rare knowledge that sometimes cleaning the house meant more than building a fortress. It meant letting people learn to stand on their own. It meant letting the White Wolf teach a blind girl to fight—not to glorify violence, but to meet a cruel world with dignity.

In time, reporters stopped using the phrase “blind girl” as if it were an epithet. They used “Lucy Westfield” with something like the inflection that names merit. Women came to watch her demonstrations and then enrolled in classes where Sarah taught not only strikes but how to hear the world as a map. Men who had once plotted the family’s ruin came to see them—and some stayed to listen. The city’s language of power shifted by degrees. It never became saintly. It became human.

The last time Jonah saw the old arena, it was behind bars and under renovation. The city had decided the place was a risk and had seized the block. The concrete walls would be repurposed: a community center, they said. Jonah offered funds with conditions—no more tournaments, no more bloodsport. He wanted, in a small way, to atone for a single choice he had made when he was younger: the contract that had turned a crowd into a witness to a child’s death.

Sarah never sought absolution for what she had done; she only sought to keep children from dying like Luca had. That was a heavy labor, and sometimes she faltered. But Lucy was there to pull her up. One afternoon they sat in the training room and practiced a slow series of forms. Sarah watched Lucy move through them, her blind eyes gentle and proud.

“You see better now than I ever did,” Sarah whispered.

Lucy tapped the tip of Sarah’s fingers with the baton lightly, a touch like a benediction. “Not seeing is different,” she said. “But I can hear the truth in you.”

Sarah laughed, and it sounded less like an animal and more like a person whose rage had been reshaped into resolve. Jonah, standing in the doorway, felt something new and irreducible: gratitude, and a small, fierce humility. He had gone to the basement expecting to find a transgression. Instead he had found a revolution in the shape of a child learning echolocation and a woman who had re-forged her past into a shelter for the future.

The city would not forget the night the syndicates sat in cuffs. It would not forget the girl who fought without sight. But the deepest thing that survived was quieter: a family that chose to reframe legacy. Jonah had once believed the greatest protection was the wall you build around a treasure. He learned that the truest protection might be making the treasure capable of defending itself, and then standing back and trusting the person you love enough to own their strength.

Lucy grew. She trained. She learned law and languages and ways to read maps and the subtle compass that a life of hidden senses affords. Sarah aged into the role of master with a tenderness and steel that made her a legend in a different way. Jonah softened into a father whose armor had thinned at the edges to make room for love. They were not saint and martyr; they were, in the end, people who had been given a terrible, clear choice and had decided to make something of it.

Years later, when Lucy walked into a room and made men hush, it was for reasons that had nothing to do with fear. People saw that she had been given a hand in carving her destiny, and had taken it. The White Wolf taught more than survival—she taught judgment, strategy, the kind of cunning that looks like mercy. And in a small corner of a once-violent world, a father learned to trade the weight of control for a different kind of strength: trust.

At the heart of it all was a promise: that a life built on mistakes could still be redirected to protect what mattered. Jonah never stopped reckoning with the past. He answered for it in quiet acts and in the one fierce devotion that had always been worth any price: fatherhood. He watched his daughter become a person he would follow. And on nights when rain came and the house creaked and the city hummed, they would sit on the balcony and Lucy would click softly, mapping the world in small echoes, Sarah at her side, and Jonah would close his eyes and let the sound of them be his prayer.

In a world that measured strength by what it took, they had made another measure entirely: strength by what you refuse to make of someone you love.