On the night the school banned my soup, my students lined the hallway with cans and paper bowls—shivering, stubborn, and hungry for more than food.

I teach tenth-grade English in Room 214. The radiator hisses like a serpent in winter, the clock sticks at 2:17 every afternoon, and the ceiling tiles carry water stains shaped like the Great Lakes. Three years ago, my son died in a car crash just a mile from our house. Since then, my chest has felt like a room with all the windows nailed shut.

Soup Thursdays started by accident.

It was a cold Thursday in November. I came in with a dented pot of corn chowder—too much thyme, bacon ends I’d scraped from the freezer. I taped a sign to the door: “Soup & Poetry. No grades, only warmth.” I told myself it was for the kids—students who came in red-eyed and hollow-stomached. But truthfully, it was for me. Steam is a prayer. It fogs the windows. It fills the empty places.

That first Thursday, five showed up.

DeShawn, who naps through grammar but writes hooks that rattle the desks.

Maya, who lives in a minivan with her mother and can memorize Dickinson like incantations.

Jayden and the quiet twins, who rarely speak but return library books two days early.

And Mr. Greene, our gray-bearded security guard, who somehow always needs to “check the paper towels” at 3:10 sharp.

I rang a little bell once, and DeShawn read a sixteen-bar riff on Langston Hughes and cafeteria pizza. Maya whispered, “Hope is the thing with feathers,” while soup fogged her glasses. Mr. Greene cleared his throat and admitted his late wife used to hum while she stirred. I read a clumsy poem I’d written at 2 a.m., my hand shaking around the spoon as if it were a microphone. They clapped anyway.

By the fourth week, we’d doubled. A cheerleader with a sprained ankle. A freshman who stuttered when he spoke but not when he read. A mother from the shelter with a toddler balanced on her hip. The pot emptied faster than I could refill it. Someone filmed a TikTok—steam, laughter, my chipped ladle—and thirty thousand strangers tapped a little red heart.

That’s when the email came.

Subject: Concerns Regarding After-School Food Distribution.

Words like liability. Words like allergies. Words like lack of alignment with district goals. The closing line: Please discontinue until further notice.

I sat at my desk, staring at those words until they blurred. My hand found my son’s rubber bracelet on my wrist, blue and fraying. I have worn it every day for three years, a superstition and a scar. I thought about the roadside cross. I thought about how grief had taught me to teach commas and context while secretly living inside silence.

That Thursday, I came anyway—with an empty pot.

The February halls were bitter. My door was cracked. And there they were, lining the wall: a river of kids and adults, each holding something. Cans of chicken noodle. Styrofoam bowls. Plastic spoons. A slow cooker someone had smuggled from home. Mr. Greene wheeled in a janitor’s cart like a parade float.

“Ms. A,” DeShawn said, voice shaking despite his grin, “if you can’t cook, we’ll bring the soup to you.”

I wanted to scold them. To wave the email. To remind them of rules. Instead, I set the empty pot on the desk like a crown. I slid the blue bracelet from my wrist and placed it beside the bell. Then I rang it twice.

Two rings means: speak the hard thing.

Maya stepped forward. “We got kicked out of the church lot last night,” she said, eyes on the floor. “A lady gave us a blanket. It smelled like her house. It helped.”

The freshman raised his hand. “My mom’s chemo makes everything taste like pennies. Could we make soup that tastes like… not pennies?”

Mr. Greene leaned on the cart, his eyes shining. “My wife’s secret,” he said softly. “A splash of apple cider vinegar to brighten the broth.” He tilted his chin at the ceiling as if he could still see her nodding.

We didn’t light burners. We didn’t measure spices. We pulled back tin lids, passed bowls down the hallway, and read poems between spoonfuls. We learned that the sigh a can makes when it opens can sound holy.

The next morning, a photo of our hallway hit the local paper. Then the superintendent’s inbox. Then the phone calls began:

— A church down the block offered their certified kitchen.

— The corner store volunteered carrots and onions.

— A retired nurse said she’d supervise allergies and keep a log.

— Parents signed waivers.

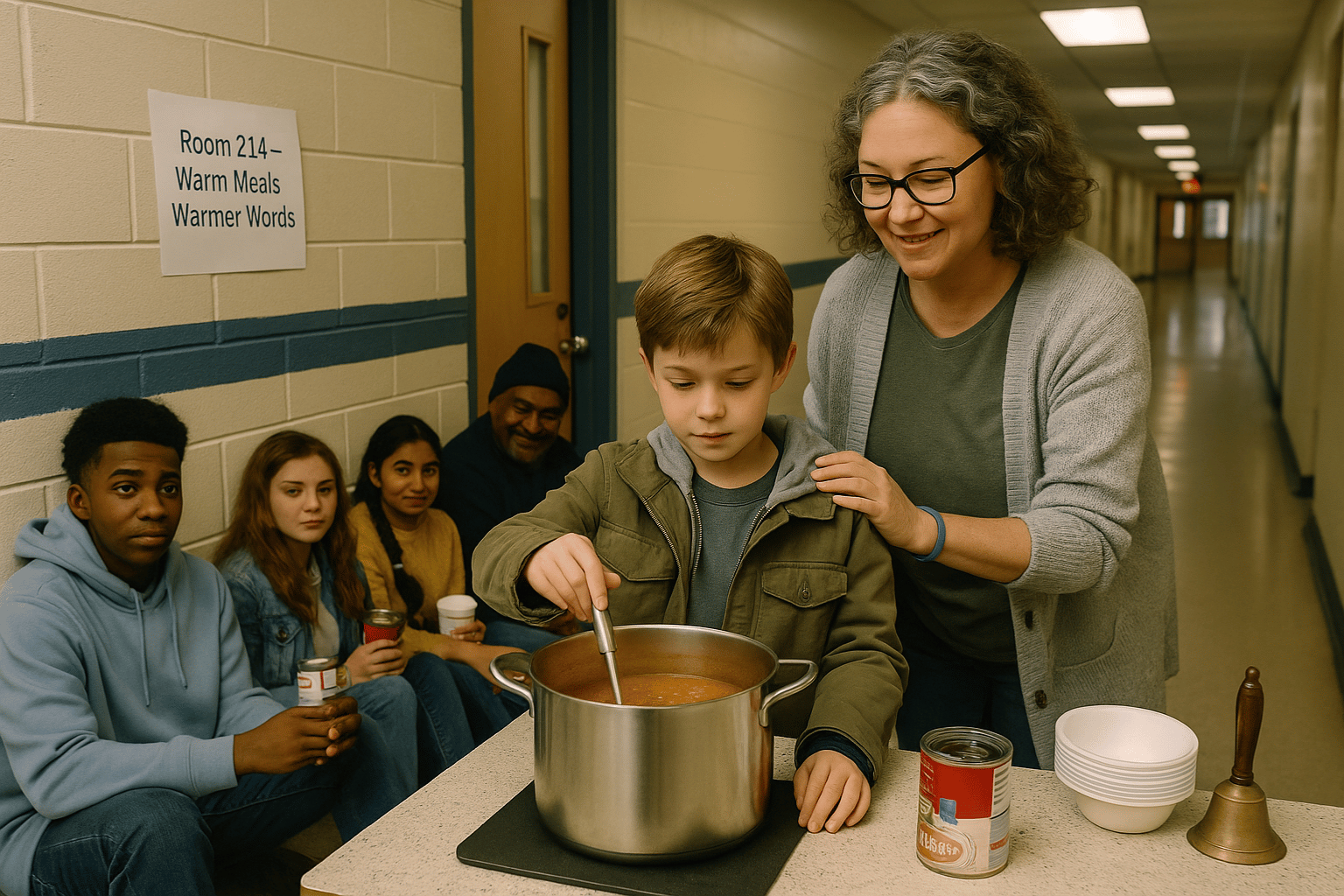

Someone 3D-printed a sign for my door: “Room 214 — Warm Meals, Warmer Words.”

The district caved, calling it a “six-month pilot program” with protocols and paperwork no poem could survive. Mr. Greene and I filled out forms at the copier while he told me about his first date—a bowling alley, gutter bumpers, the strike that won his wife’s laugh.

Yesterday, a new boy hovered in the doorway. Quiet. Thin coat. Eyes down.

“Ms. Alvarez,” he whispered, “my mom’s sick. Can you teach me to make soup?”

I pressed the spoon into his hand. It was heavier than he expected. Most mercy is.

“First,” I told him, “you stir. Then you talk.”

He stirred. We listened. Someone rang the bell once for poetry.

Here’s what I know now: Policy can count minutes and calories, but kindness counts breaths. You don’t fix a starving country with one pot of soup. You teach a hundred trembling hands how to stir—and to speak while the steam is rising.