The air in the taxi smelled like stale pine air freshener and old vinyl, but to me, it smelled like freedom.

I checked my watch for the tenth time in two minutes. 10:15 AM. Recess was in fifteen minutes. I smoothed out the wrinkles in my OCPs. I hadn’t even had time to change. I’d hopped a hop from Bagram to Ramstein, then a long haul to Dover, and finally, a connection to Texas.

Eighteen months. That’s how long it had been since I’d seen Avery. She was seven when I left. She’d be turning nine next month. My hands, usually steady enough to thread a needle in a sandstorm, were shaking. Not from fear. From excitement.

I pictured her face. That gap-toothed smile she probably didn’t have anymore. The way her eyes would light up when she saw me standing by the playground fence.

“We’re here, Sarge,” the driver said, pulling up to the curb of Riverbend Elementary.

The school looked exactly the same. Red brick. White trim. The American flag snapping in the wind on the front pole. I paid the driver and tipped him twenty bucks. “Thanks for getting me here fast.”

“Thank you for your service, son. Go get her.”

I grabbed my duffel bag, slung it over my shoulder, and walked toward the front office. The secretary, an older woman with glasses on a chain, nearly dropped her coffee mug when I walked in.

“Can I hel— oh my goodness,” she stammered, standing up.

“I’m Cole Anderson,” I said, my voice rough from the dry air of the flight. “I’m Avery Anderson’s father. I just got back. I was hoping to surprise her.”

Her eyes went wide. Then they softened. “She’s in Mrs. Whitmore’s class. Room 304. Down the hall, take a left. They’re in the middle of a lesson, but… I think we can make an exception for this.”

She handed me a visitor pass. “Welcome home, Mr. Anderson.”

“Thanks.”

I walked down the hallway. It was quiet. That specific kind of school-quiet where you can hear the hum of the vending machines and the squeak of your own boots on the waxed linoleum. I passed artwork taped to the walls. Hand turkeys. Watercolors of houses. I scanned them, looking for Avery’s name. I didn’t see it.

My heart was hammering against my ribs. I turned the corner toward Room 304. I was practicing what I’d say. Hey, pumpkin. No, too cheesy. Avery, look who’s here.

I was ten feet away from the door when I heard it.

It wasn’t the sound of children laughing. It wasn’t the drone of a teacher reciting multiplication tables. It was yelling. Sharp. High-pitched. Venomous.

“I am sick and tired of your excuses!”

I stopped. The voice was coming from Room 304.

“Look at you! Look at this mess!”

Then, a small, terrified voice. A voice I knew better than my own heartbeat.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Whitmore… I forgot my…”

“Forgot? You always forget! You forget because you don’t care! You forget because you come from a broken home with no structure!”

My blood turned to ice. I stepped closer to the door. There was a thin vertical window reinforced with wire mesh. I looked inside.

The classroom was dead silent. Twenty kids were frozen at their desks, eyes wide, terrified.

At the front of the room, standing by the chalkboard, was a woman. She was tall, wearing a sharp grey suit that looked too expensive for a public school teacher. Her blonde hair was pulled back so tight it looked painful.

And there was Avery. She was standing in front of the class. My little girl. She looked smaller than I remembered. Her clothes—a pink t-shirt and jeans—looked worn. Faded. She was trembling. Her head was bowed, her chin touching her chest.

Mrs. Whitmore was towering over her.

“Look at me when I’m talking to you, Avery!” she shrieked.

Avery flinched but slowly lifted her head. Tears were streaming down her cheeks. “I… I didn’t mean to…”

“You never ‘mean’ to,” Mrs. Whitmore sneered. She turned to the rest of the class. “Class, look at Avery. This is what happens when you don’t take your education seriously. This is what happens when you rely on handouts.”

I gripped the door handle. My knuckles turned white. I wanted to kick the door off its hinges. But I needed to know. I needed to see exactly what I was dealing with.

Mrs. Whitmore turned back to Avery. She picked up a ruler from her desk. It wasn’t a plastic one. It was one of those old-school metal ones with the cork backing. Heavy. Sharp edges.

“You didn’t bring your project money,” Mrs. Whitmore said, tapping the ruler against her own palm. Thwack. Thwack.

“Mommy said… Mommy said she gets paid on Friday,” Avery sobbed.

“Mommy said,” Mrs. Whitmore mocked, using a high, whiny voice. “Your mother is always late. Just like you. It’s pathetic. Honestly, I don’t know why the district lets people like you into this school. You bring the property value down just by existing.”

The rage that filled me wasn’t the hot, adrenaline-fueled rage of combat. It was cold. It was dark. It was absolute.

Mrs. Whitmore took a step closer to my daughter. “You are a waste of space in my classroom, Avery Anderson.”

She raised the metal ruler. She didn’t hit her. Not in the way you’d expect. She jammed the end of the ruler into Avery’s cheek. Hard.

Avery gasped, stumbling back, clutching her face.

“Stand still!” Mrs. Whitmore barked, pressing the ruler against my daughter’s skin again, pushing her head back. “I am trying to teach you something! Since your father clearly didn’t care enough to stick around to do it!”

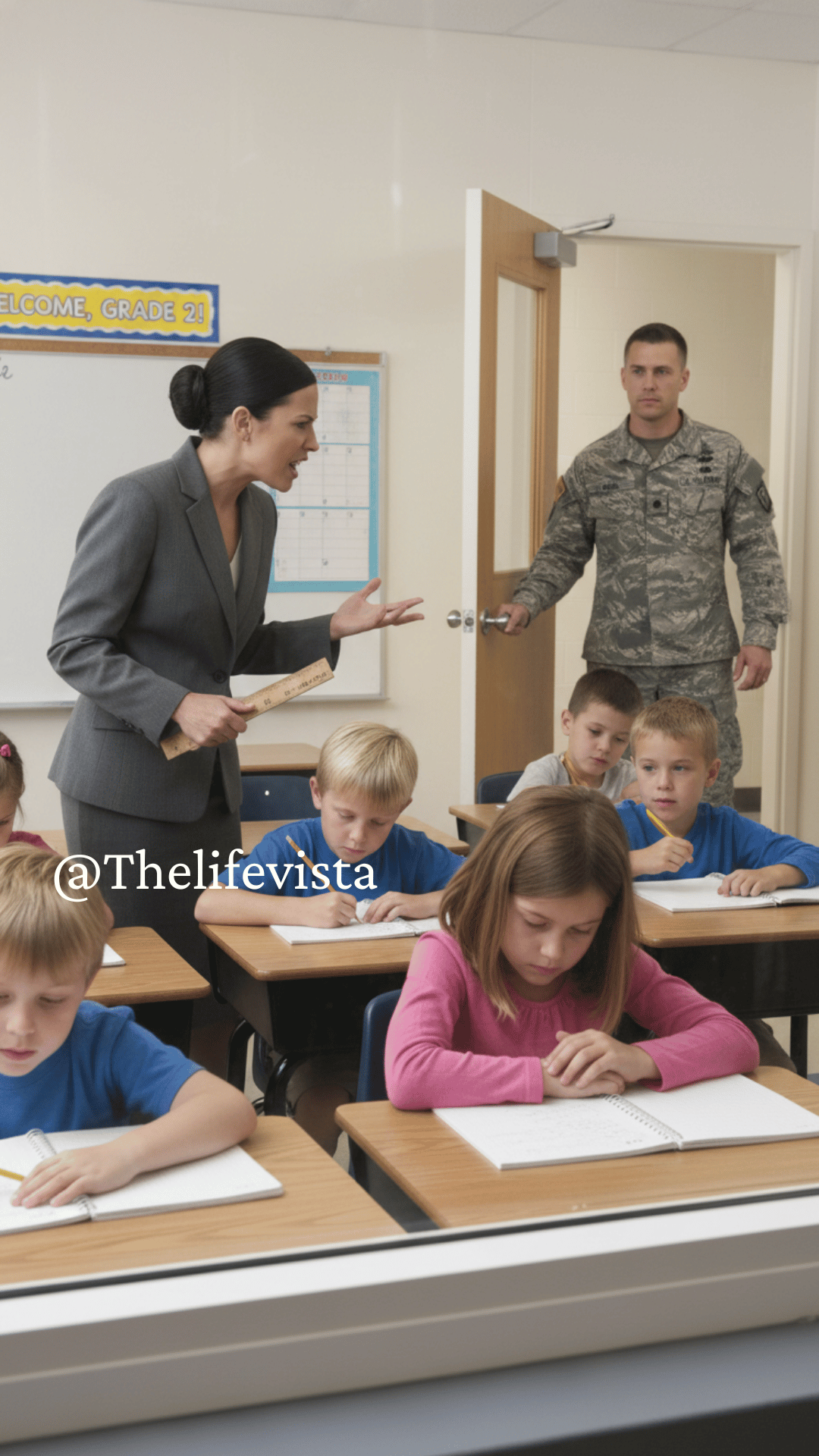

That was it. The world narrowed down to a single point. I didn’t think. I didn’t plan. I turned the handle.

The door swung open. It didn’t bang. It just clicked and drifted open, bringing with it the sudden draft of the hallway.

The sound in the room vanished. Mrs. Whitmore froze, the ruler still pressed against Avery’s cheek. She turned her head, annoyed at the interruption.

“I told the office I am not to be disturb—”

Her words died in her throat. I stepped into the room. Six foot three. Two hundred and twenty pounds. Combat boots. OCP camouflage. And a look on my face that had made grown men in interrogation rooms wet themselves.

I didn’t look at the class. I didn’t look at the chalkboard. I looked straight at her hand. The hand holding the ruler against my baby’s face.

“Get that thing,” I said, my voice low, like gravel grinding in a mixer, “off my daughter.”

Mrs. Whitmore’s eyes went wide. She looked at my uniform. She looked at my face. She pulled the ruler back as if it were suddenly burning hot.

Avery turned. Her tear-filled eyes locked onto mine. For a second, she looked confused. Like she was seeing a ghost. Then, her face crumbled.

“Daddy?” she whispered.

Mrs. Whitmore stumbled back, hitting her hip against her desk. “I… I… Who are you?”

I ignored her. I dropped my duffel bag on the floor with a heavy thud. I walked over to Avery. I dropped to one knee. There was a red mark on her cheek where the metal had dug in. I gently brushed a tear away with my thumb.

“I’m here, baby,” I said softly. “I’m here.”

Avery threw her arms around my neck, burying her face in the rough fabric of my uniform. She screamed. It wasn’t a happy scream. It was a scream of release. Of months of torture being let go. I held her tight. I held her until I could feel her heartbeat slowing down.

Then, I stood up. I kept Avery tucked behind my leg, shielding her. I turned to Mrs. Whitmore. The color had drained from her face completely. She was gripping the edge of her desk, the metal ruler still in her other hand.

“You said something about her father,” I said. I took a step toward her. The entire class was watching. You could hear a pin drop.

“I… Mr. Anderson, I presume?” she stammered, trying to regain her composure, trying to put that mask of superiority back on. “I was just… we were having a disciplinary moment. Avery has been very… difficult.”

“Difficult?” I repeated. I took another step. She backed up until she hit the chalkboard. “You told her she was a waste of space. You told her she didn’t deserve to be here.”

“I… I was using hyperbole to make a point about responsibility!” she squeaked.

“And the ruler?” I asked. I pointed at it. “Was that hyperbole? Jamming a piece of metal into a nine-year-old’s face?”

“I didn’t hurt her! I was just directing her attention!”

“You want to direct attention?” I asked. I snatched the ruler from her hand. I moved so fast she didn’t even have time to flinch. I snapped the metal ruler in half with one hand. The sound was like a gunshot in the quiet room. I threw the pieces on her desk.

“You have my attention now, lady.”

“You… you can’t threaten me!” Mrs. Whitmore shrieked, her voice trembling. “I’m a tenured educator! I will have you removed from this campus!”

“Oh, I’m not leaving,” I said, crossing my arms. “And neither are you. Not until the police get here.”

“The police?” She laughed, a nervous, hysterical sound. “For what?”

“Assault,” I said. “Assaulting a minor. And I’m pretty sure there’s twenty witnesses right here.”

I looked at the class. “Did she hit her?” I asked the room.

A little boy in the front row, wearing a superhero shirt, nodded slowly. “She pokes us all the time,” he whispered.

Mrs. Whitmore gasped. “Jimmy! You liar!”

“Don’t you talk to him!” I roared. My voice shook the windows. She flinched, covering her face.

“You like using your power on people smaller than you?” I stepped right into her personal space. “How does it feel? How does it feel when the person standing in front of you is bigger? Stronger? Angrier?”

“Please,” she whimpered.

“You told her she came from a broken home,” I hissed. “You have no idea what this family has sacrificed so you can stand in this air-conditioned room and terrorize children. You have no idea.”

“I didn’t know!” she cried. “I didn’t know you were… serving.”

“Oh,” I smiled, but there was no humor in it. “So if I was a plumber, or a banker, or unemployed… it would be okay to abuse my kid? That’s what you’re saying?”

“No! I…”

The door opened behind me. “What on earth is going on here?”

It was the Principal. A short, balding man in a cheap suit.

Mrs. Whitmore let out a breath of relief. “Mr. Donahue! Thank God! This man… this man barged in! He’s threatening me! He’s violent! He’s having a PTSD episode or something! Call 911!”

The Principal looked at me. He looked at the snapped ruler on the desk. He looked at Avery, who was clinging to my leg, weeping. He looked at the red mark on her face.

“Mr. Anderson?” the Principal asked.

“Yeah,” I said, not taking my eyes off the teacher.

“Did you… touch Mrs. Whitmore?”

“Not yet,” I said.

Mrs. Whitmore pointed a shaking finger at me. “He destroyed school property! He’s unhinged! Look at him!”

The Principal walked over to Avery. He crouched down. “Avery,” he said gently. “Did Mrs. Whitmore do that to your cheek?”

Avery nodded, burying her face in my leg again.

The Principal stood up. His face changed. The bureaucratic look vanished, replaced by something grim. He turned to Mrs. Whitmore.

“Pack your things, Agatha.”

“Excuse me?” she screeched.

“Pack your things. Get out of my school. Go to the district office. Do not pass go. Do not speak to anyone.”

“You can’t do this! I have tenure!”

“You assaulted a student,” the Principal said, his voice cold. “In front of a decorated serviceman who just walked in the door. You’re lucky he didn’t put you through that wall. I would have looked the other way.”

I hailed a cab. I didn’t want to wait for Claire to get off work. I needed to get my daughter to a safe zone.

“Where to?” the driver asked.

“Dairy Queen,” I said. “The one on Main.”

It was our spot. Before I deployed, we’d go there every Friday. It was a tradition. I thought maybe, just maybe, some ice cream would wash the taste of fear out of her mouth.

We sat in a red vinyl booth. I ordered her a Dilly Bar and a chocolate shake. I got a coffee, black.

Avery stared at the ice cream. She didn’t touch it.

“Not hungry?” I asked gently.

She shook her head. She was picking at the skin around her fingernails. I noticed then that her nails were bitten down to the quick. Raw. Bleeding in spots. She never used to do that.

“Avery,” I said, leaning forward. “Talk to me. That teacher… Mrs. Whitmore. How long has she been doing that?”

Avery looked out the window. A tear slid down her nose.

“Since the beginning of the year,” she whispered.

“Did you tell Mom?”

“No.”

“Why not, sweetie?”

She looked at me then, and the maturity in her eyes broke my heart. “Because Mommy cries at night when she thinks I’m asleep. She talks to the bills. She says, ‘I don’t know how we’re going to do it.’ I didn’t want to be another problem.”

I closed my eyes.

She talks to the bills.

While I was out there, thinking I was providing, thinking the Army pay was handling everything, my wife was drowning. And my daughter was drowning with her, in silence, to protect us.

“The project money,” I said, opening my eyes. “The ten dollars?”

“It wasn’t just the money,” Avery said, her voice trembling. “Mrs. Whitmore… she has a list. She calls it the ‘Trash List’.”

My jaw tightened. “The what?”

“The Trash List. She puts names on the board. Me. Leo. Sarah J. The kids who get free lunch. The kids whose clothes aren’t new.”

I felt the blood rushing in my ears. The sound of the ice cream machine humming in the background faded away.

“What does she do to the kids on the list?” I asked, my voice dangerously calm.

“She makes us sit in the back. She checks our homework harder. If we get one thing wrong, she makes us stand up and tells the class we aren’t trying. She says… she says we’re destined to be ‘service workers’ so we better get used to standing.”

Avery looked down at her melting Dilly Bar.

“And she pokes us. With the ruler. Or the pointer. She says she has to ‘wake us up’ because poor people are lazy.”

I gripped my coffee cup so hard the Styrofoam cracked, spilling hot liquid onto my hand. I didn’t even feel the burn.

This wasn’t just a bad teacher having a bad day. This was a predator. A sadist targeting the most vulnerable kids in her room because she knew their parents were too busy working two jobs, or too scared, or too absent to fight back.

She had picked my daughter because she thought I was gone. Because she thought Claire was weak.

She had made a grave calculation error.

“Eat your ice cream, baby,” I said, wiping my hand with a napkin. “We’re going to go see Mommy. And then… Daddy has some work to do.”

“What kind of work?” she asked, fearful again.

I reached across the table and took her hand. I squeezed it gently.

“Cleaning up the trash,” I said.

The reunion with Claire was everything I had dreamed of, and everything I feared.

I walked into our small rental house—a place I hadn’t seen in a year and a half. It was cleaner than a barracks for inspection, but it felt empty. The furniture was different. We used to have a big leather sectional. Now there was a cheap futon.

Claire was in the kitchen, still in her nurse’s scrubs. She looked exhausted. Dark circles under her eyes, grey hairs that hadn’t been there before.

When she saw me standing in the doorway, holding Avery’s hand, she dropped the spatula she was holding.

“Cole?”

We collided in the middle of the living room. She smelled like antiseptic and lavender soap. I buried my face in her neck and just breathed. For a minute, the world was right.

But the peace didn’t last. It couldn’t.

After the tears, after the hugging, after Avery went to her room to play with the stuffed bear I’d brought her, we sat at the kitchen table.

I told Claire everything. The classroom. The ruler. The “Trash List.”

Claire went pale. She put her head in her hands.

“Oh my God,” she sobbed. “I knew she was strict. I knew Avery didn’t like school. But I thought… I thought maybe Avery was just adjusting to you being gone. I didn’t know.”

“It’s not your fault,” I said firmly. “You were holding down the fort. You were surviving.”

“I should have known,” she whispered. “I’m her mother.”

“We know now,” I said. “And we’re going to fix it.”

I was about to tell her my plan—to go to the school board, to call the local news—when my phone buzzed.

It was an unknown number.

“Hello?” I answered.

“Mr. Anderson?” The voice was male, smooth, professional.

“Speaking.”

“This is Detective Morgan with the Riverbend Police Department. I need you to step outside, sir.”

My stomach dropped. I looked at Claire. Her eyes went wide.

“Why?” I asked.

“Just step outside, Mr. Anderson. We need to have a conversation about an incident at the elementary school this morning.”

I hung up.

“What is it?” Claire asked, panic rising in her voice.

“Police,” I said. “Stay here.”

I walked out to the front porch.

There was a cruiser parked at the curb. Two officers. One was leaning against the car, hand resting near his belt. The other, the detective presumably, was walking up the driveway.

He wasn’t aggressive, but he wasn’t friendly either.

“Mr. Anderson,” he said, stopping at the bottom of the steps. “I understand you had a confrontation with a Mrs. Eleanor Whitmore today.”

“I stopped a woman from assaulting my child,” I corrected him. “Is she in custody?”

The detective sighed. He pulled a notepad out of his pocket.

“Mrs. Whitmore has filed a sworn statement claiming you burst into her classroom, destroyed school property, and threatened to kill her. She claims you were, and I quote, ‘in a manic, violent state.’”

I laughed. It was a cold, sharp sound. “She jammed a metal ruler into my daughter’s face. There are twenty witnesses.”

“We’re interviewing the staff,” the detective said. “But here’s the problem, Mr. Anderson. The Principal… Mr. Dalton? He’s changing his tune.”

I froze. “What do you mean?”

“He told us you were aggressive. That he had to de-escalate the situation. He didn’t mention any assault on the child. He said Mrs. Whitmore was conducting a lesson and you interrupted.”

My hands curled into fists at my sides. Principal Dalton. The little man who had told her to pack her bags. He had flipped. In less than three hours.

“Why would he lie?” I asked.

The detective looked around, then lowered his voice. He took a step closer.

“Look, soldier to soldier? I did two tours in Iraq.”

I looked at him. I saw the weariness in his eyes.

“Mrs. Whitmore’s husband is Charles Whitmore,” Detective Morgan said quietly. “President of the School Board. And his brother is the City Attorney.”

The pieces clicked into place. The arrogance. The immunity. The “tenure” comment.

She wasn’t just a teacher. She was royalty in this small town. And I was just a grunt who had kicked the hornet’s nest.

“So what are you saying?” I asked. “I’m under arrest?”

“Not yet,” Morgan said. “But she’s filed for an emergency restraining order. You are banned from school property. If you go within five hundred feet of that woman or the school, I have to bring you in. And with your… status… they’ll paint you as a PTSD case about to snap. They’ll take your kid, Cole.”

The threat hung in the heavy afternoon air.

They would take my kid.

If I fought this the way I wanted to—with noise, with anger, with force—they would use it against me. They would spin the narrative.

Unstable Veteran Terrorizes Beloved Teacher.

I felt a trap closing around me. A trap made of paperwork, lies, and local politics.

“Thanks for the heads up,” I said, my voice flat.

“Keep your head down,” Morgan warned. “These people… they play dirty.”

He walked back to his car.

I stood on the porch, watching them drive away.

I looked at the front door of my house. Inside were my wife and my daughter. The two people I had fought to get back to.

And now, a woman with a ruler and a powerful last name was trying to destroy us.

I reached into my pocket and pulled out my phone. I opened the browser.

I typed in the school’s name.

There it was. A post on the local community Facebook page, posted twenty minutes ago.

Community Alert: A terrifying incident at Riverbend Elementary today.

A violent intruder threatened our beloved Mrs. Whitmore.

We must protect our teachers from unstable individuals!

It had 200 likes already. Comments were pouring in.

Prayers for Eleanor!

Who let this maniac in?

Is the school safe?

They were rewriting history before the ink was even dry.

I turned off the phone.

I wasn’t going to yell. I wasn’t going to punch a wall.

I went back inside. Claire was standing there, terrifyingly pale.

“Cole?”

I walked over and kissed her forehead.

“It’s okay,” I lied.

“What did they want?”

“They wanted to scare me,” I said. I walked to the kitchen drawer and pulled out a notepad and a pen.

“What are you doing?”

I sat down at the table. I thought about the mission. Assess the enemy. Find the weakness. Exploit it.

Mrs. Whitmore had power. She had the school board. She had the police chief’s ear.

But she had twenty witnesses. Twenty children.

And she had made one mistake.

She had underestimated the “Trash.”

“I’m making a list,” I said to Claire.

“A list of what?”

“Of every parent whose kid has been in Room 304,” I said. “Mrs. Whitmore likes lists. I think it’s time she saw mine.”