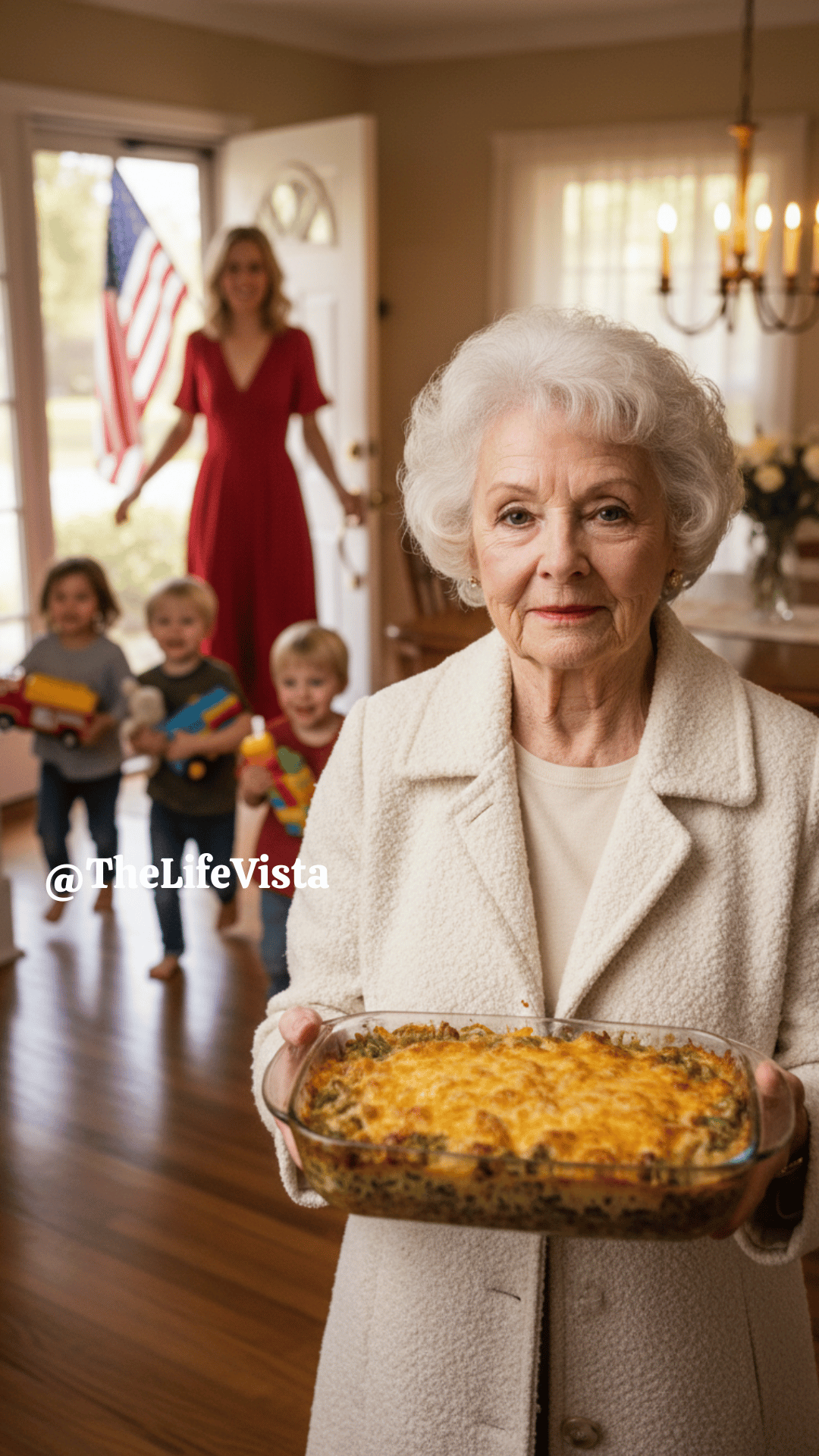

I set the green bean casserole down on the kitchen counter, still warm from my oven three blocks away, and untied my apron. My hands were shaking, but not from the cold November air I’d just walked through. They were shaking because I’d finally heard it—the thing I’d been pretending not to notice for the last two years.

“Why don’t you eat in the kitchen, Mom?” my son, Michael, said. “Lauren and I need the dining room for our actual guests.” He said it so casually, like he was asking me to pass the salt, like I wasn’t his mother, like I hadn’t spent the last six weeks preparing for this Thanksgiving dinner in his new house—the house I’d helped with the down payment, though we didn’t talk about that anymore.

I picked up my purse from the hook by their front door. I didn’t say goodbye. I didn’t make a scene. I just walked out, leaving behind the casserole I’d made with my mother’s recipe, the pumpkin pies cooling on their granite countertop, and twenty-three years of convincing myself that my son’s coldness was just his way of being independent.

The walk home was longer than three blocks. It felt like miles.

I’m Eleanor, though most people call me Ellie. I’m sixty-seven years old, and until that Thanksgiving evening, I thought I knew exactly who I was: a retired librarian, a widow of four years, a mother of two—Michael, thirty-nine, and my daughter, Anna, thirty-six—a grandmother of three, and a woman who’d spent her whole life taking care of everyone else, believing that’s what love looked like.

That’s what I thought, anyway.

It started small, the way these things always do—little comments that felt like paper cuts. Lauren, my daughter-in-law, started calling me Eleanor instead of Mom about six months after their wedding. When I asked Michael about it, he shrugged and said, “She has her own mother, you know.” Fair enough, I told myself. Not everyone wants to call their mother-in-law Mom, so I didn’t push it.

Then came the requests. Could I watch the kids on Saturday? Could I pick up groceries? Could I help with the house cleaning before their dinner party? Each time I said yes because that’s what grandmothers do, isn’t it? We help. We show up. We make life easier for our children.

I didn’t notice when “Can you help?” turned into “You should come over and watch the kids.” I didn’t notice when they stopped asking and started expecting. I didn’t notice when I became less like family and more like staff.

But I noticed on Thanksgiving.

I arrived at two in the afternoon, just like Lauren had texted me to do—not asked, told. Be here at 2. The kids need watching while we prep. No please. No if you’re free. Just an order. When I got there, the house was chaos. Seven-year-old Sophie and five-year-old Noah were running through the living room, and Lauren was on her phone coordinating with the caterer.

The caterer. For the meal.

I’d thought I was helping to cook.

“Oh, good. You’re here,” Lauren said, not looking up from her phone. “Can you keep the kids in the playroom? They’re driving me insane. And Michael said you were bringing that green bean thing, so just put it wherever.”

That green bean thing. My mother’s recipe—the dish I’d made every Thanksgiving since Michael was born. I swallowed the sting and smiled at Sophie and Noah anyway.

“Want to play a game with Grandma?” I asked.

Sophie looked at her mother first, like she needed permission to see me. “Mom said we have to stay in the playroom when the important people get here.”

“The important people,” I repeated, and something cold settled in my chest.

“Yeah,” Noah said, already losing interest in me. “Mom’s friends from her book club and Dad’s boss. We’re not allowed in the dining room.”

Neither am I, apparently, I thought, but I didn’t say it.

I spent the next four hours in that playroom reading stories and playing endless rounds of Candy Land while I listened to laughter spilling from the other room. Every so often, Michael would poke his head in to grab something, never quite making eye contact with me.

“Dinner’s almost ready,” he’d say. “You okay in here?”

Was I? I didn’t know anymore.

At 6:30, Lauren appeared in the doorway. She was wearing a beautiful burgundy dress, her hair perfectly styled, the kind of look you wear when you want people to see you as polished and effortless. She looked at me in my comfortable sweater and slacks, and I saw something flicker across her face—embarrassment, maybe, or annoyance that I didn’t match the aesthetic.

“The kids can eat in here,” she said. “I’ll bring plates.”

“What about me?” The question came out before I could stop it.

Lauren blinked, like the idea hadn’t occurred to her. “Well, you’re watching them, right? You can eat with them. We have eight people in the dining room and, honestly, Eleanor, you’ll be more comfortable in here anyway. You know how stuffy dinner parties can be.”

I stood up slowly. My knees popped—something that had been happening more lately, a reminder that I wasn’t young anymore, that I was, in their eyes, replaceable.

“Actually,” I said, “I think I’ll head home.”

“But you haven’t eaten,” Lauren said, and I almost laughed at the sudden concern in her voice, like this was about my hunger and not my place.

“Almost,” I said. “I’m not very hungry.”

That’s when Michael appeared behind his wife, his face already tight with irritation. “Mom, don’t be dramatic. It’s just dinner. Stay in here with the kids. They’d love it.”

“In the kitchen?” I corrected quietly.

He frowned. “What?”

“That’s what you said,” I told him. “I should eat in the kitchen because you need the dining room for your actual guests.”

His face went red. “I didn’t mean it like that.”

“How did you mean it, Michael?” I asked.

He didn’t answer. Neither did Lauren. They just stood there, blocking the playroom doorway like I needed permission to leave.

And something in me went still. I realized I was done—done explaining, done pretending this was normal, done convincing myself love was supposed to feel like this.

“I’m going home,” I said again.

“But the casserole—” Lauren started.

“Keep it,” I said. “Share it with your actual guests.”

I kissed Sophie and Noah on their heads, grabbed my purse, and walked past my son and his wife through their beautiful living room with its professional family photos—photos I wasn’t in because Lauren said they wanted “just the immediate family.” I passed the dining room table set for eight, with the good china and crystal I’d given them as a wedding gift, and I walked out the front door into the November darkness.

I didn’t cry on the walk home. I was too numb for tears.

My house was exactly as I’d left it, a small three-bedroom ranch I’d lived in for thirty-two years. After my husband, Thomas, died four years ago, everyone expected me to sell it. Too big for one person, they said. Too much maintenance. Michael had been especially insistent that I downsize, move into a senior apartment, maybe something closer to them so they could keep an eye on me.

Now I understood. Closer meant more available. More useful.

I’d kept the house out of stubbornness, I suppose. Or maybe some part of me had known I’d need a place that was entirely mine.

That night, I sat in my kitchen and ate a turkey sandwich. The house was quiet except for the hum of the refrigerator and the steady ticking of the clock Thomas’s mother had given us. I looked around at my small, comfortable kitchen—at the herbs growing in pots on the windowsill, at the recipes pinned to the corkboard, at the photo of my kids from fifteen years ago back when Michael still hugged me—and I felt something I hadn’t felt in a long time.

Space.

My phone buzzed. A text from Michael: Mom, you’re being ridiculous. Come back. It’s Thanksgiving.

I turned my phone off.

The next morning, Anna called. My daughter lived in Seattle, about as far from our Indiana town as she could get while still staying in the continental U.S. She’d moved there for graduate school and never came back, something I’d never quite forgiven her for. We talked every few weeks—polite conversations about work and weather and nothing that mattered.

“Mom,” she said, and her voice was careful, “are you okay? Michael texted me. He said you walked out of Thanksgiving dinner.”

“I’m fine,” I said automatically.

“You’re not,” Anna said. Then, after a pause that made my chest tighten, she surprised me. “Good.”

“What?” I said.

“I said, good,” she repeated. “It’s about time you stood up to him.”

I sat down heavily on my couch, like my legs had suddenly remembered they were tired. “You knew about how they’ve been treating me?”

Anna sighed, long and weary. “Mom, I’ve been watching it happen for two years. Every time I visit, I see it. The way Lauren talks to you like you’re the help. The way Michael just lets it happen. I tried to tell you last Christmas, remember?”

I did remember. Anna had pulled me aside after a particularly uncomfortable dinner and said, “Mom, you don’t have to take this,” and I’d brushed her off, told her she was being oversensitive, that Michael and Lauren were just stressed with work and the kids.

I hadn’t been ready to hear it then.

“I wasn’t ready,” I admitted.

“Are you ready now?” she asked.

Was I?

I looked around my living room at the life I’d built, the space that was mine, the quiet that didn’t demand anything from me. “Yes,” I said. “I think I am.”

“Then come to Seattle for Christmas,” Anna said quickly, like she’d been holding the invitation in her mouth for a long time. “Please stay with me. No obligations, no watching kids, no being treated like you’re invisible—just us.”

The invitation hung in the air.

“I’d like that,” I said.