I’m standing behind the counter of my diner for the last time. It’s December 15th, 2022. And after 43 years, Parker’s diner is closing its doors forever. The bank’s coming tomorrow to take the keys. I’m 68 years old, broke, and saying goodbye to the only thing I have left of my wife. But then, three strangers walk in with a lawyer, and one of them says something that stops my heart. Mr.

Parker, do you remember the blizzard of 1992?

It’s 6:00 a.m. on a Thursday morning in December, the coldest day of the year so far in Valentine, Nebraska. A small town on Highway 20, halfway between nowhere and nothing.

Population’s been declining for 20 years. Ever since the meat packing plant closed and the young people started leaving for Omaha or Denver or anywhere with more opportunity than a dying prairie town could offer, I’ve been awake since 4, like I have been every morning for the past 43 years. Old habits don’t die just because your business is dying. I lay in bed for an hour in the apartment above the diner.

The same apartment Linda and I moved into in 1979 when we were 25 years old and stupid enough to think we could make a living selling eggs and coffee in rural Nebraska. The same bed where she died 3 years ago, holding my hand, telling me to keep the diner open, to not give up. I gave up anyway.

Not right away, but slowly, month by month, bill by bill, until there was nothing left to do but surrender. I unlock the front door of Parker’s diner, flip on the lights, and stand there for a moment, looking at the place I built with my own hands. Red vinyl booths along the windows. Recovered twice in 1991 and 2008, getting more expensive each time. A long formica counter with chrome-legged stools.

Some of them wobbling now because the welds are old and I can’t afford to fix them. A jukebox in the corner that hasn’t worked since 2003, but I can’t bring myself to throw away because Linda loved that jukebox. Used to play Patsy Cline while she waited tables. The walls are covered with photos, layers of them, decades of them overlapping like pages in a scrapbook.

Customers celebrating birthdays. Local high school sports teams after championship games. The Valentine High School class of ’89 after prom. All of them crammed into the back room in their tuxedos and puffy dresses. The annual pancake breakfast fundraiser that we hosted for 35 years straight.

Community events from four decades of being the heart of this town. There’s a photo of me and Linda on opening day front and center above the register. Both of us 25 years old grinning like idiots in front of our brand new diner. She’s wearing her waitress uniform, pink dress with white apron, her name embroidered on the pocket, hair pulled back in a ponytail.

I’m in my cook’s apron, skinny as a rail back then. Full head of brown hair that’s now completely gray. We look like we’re going to live forever. Like nothing bad will ever happen to us. Like this diner will outlast us both. Two out of three wasn’t bad. Linda died two years ago, 2020, right before the pandemic hit.

And the world went insane. Pancreatic cancer, diagnosis to death in 4 months. She spent her last weeks in the apartment upstairs in our bed, looking out the window at the diner below. Sometimes customers would wave up at her. She’d wave back even when she was too weak. “Promise me you’ll keep it open,” she said 3 days before she died.

Her voice was barely a whisper. The diner. It’s our legacy, Frank. It’s what we built together. I promise. I said I tried. God knows I tried, but the pandemic destroyed us. We went to take out only for 18 months. Lost 70% of our revenue. The overhead stayed the same. Rent, utilities, insurance, equipment leases.

I took out loans I couldn’t afford, maxed out credit cards, applied for every grant, every assistance program. Some helped, most didn’t. By 2021, I was underwater. By 2022, I was drowning. The bank sent the foreclosure notice in September. I had 90 days. I spent those 90 days trying to find a buyer, someone who wanted a diner in a dying town. Nobody did.

Why would they? Valentine, Nebraska wasn’t exactly a growth market. So, here we are. December 15th, 2022, the last day. Tomorrow, the bank takes the keys and Parker’s diner becomes whatever corporate chain they can sell it to. Probably a Dollar General. Everything becomes a Dollar General eventually.

I walk behind the counter, tie on my apron, the same style I wore in that photo, just 43 years more worn, the white fabric gone gray from a thousand washings, and start the coffee. The big industrial machine Linda and I bought used in 1982 that’s broken down 50 times, and I fixed it 50 times because I refused to replace it. It groans to life, gurgling and hissing, and within minutes, the smell of coffee fills the diner. Rich, dark, familiar.

The same smell that’s greeted customers every morning since 1979. Outside, the sun’s starting to come up over the Nebraska plains. December sunrise, painting the frozen grass gold and pink, long shadows stretching across Highway 20. It’s beautiful. It’s always been beautiful. That’s what Linda used to say. We might not have much, Frank, but we have this view.

We have this light that’s worth something. Worth something, but not worth $180,000. Not worth saving the diner. I crack eggs onto the grill, lay out bacon, make hash browns from scratch like I’ve done every morning for 43 years. Muscle memory. Knife work I could do blind.

The rhythm of cooking that’s been my meditation, my prayer, my way of processing life since I was younger than my customers’ grandkids. This is the last time I’ll make coffee in this diner. The last time I’ll crack eggs on this grill. The last time I’ll hear the bell above the door jingle when customers walk in.

The bell jingles. Morning, Frank. It’s Deputy Mike Turner, Sheriff’s Department, works the night shift. Stops in every morning at 6:15 for coffee and eggs before going home. Been doing it for 12 years.

Morning, Mike.

Usual.

Yeah.

And Frank. He pauses, takes off his hat. I’m real sorry about today. This town won’t be the same without this place.

Thanks, Mike.

He sits at the counter. I pour his coffee. We don’t talk.

What’s there to say? In small towns, some losses are too big for words.

The regulars have been coming by all week to say goodbye, to tell me stories about their first date here or their wedding reception in the back room or Sunday breakfast after church for 30 years straight. A lot of crying, a lot of hugging, a lot of I’m so sorry, Frank. Me, too. I’m sorry, too.

The morning rush, if you can call eight people a rush, comes and goes. The Hendersons married 62 years. Same booth by the window. Same order. Two scrambled bacon, wheat toast, split aside of hash browns. They don’t say much. Just hold hands across the table and cry quietly while they eat.

Pastor David Williams from First Lutheran. Black coffee, stack of pancakes, leaves me a $50 tip he can’t afford. The Choi family, who’ve owned the hardware store since 1989, they bring their three kids, let them order whatever they want. Chocolate chip pancakes, extra whipped cream, the works. When they leave, Mr. Choi shakes my hand, and says, “You were here when we arrived in this town. You made us feel welcome when not everyone did. Thank you.”

By noon, the lunch crowd has thinned out. Just a few stragglers. Teenagers from Valentine High School cutting class to eat burgers one last time. Old farmers nursing coffee and complaining about the weather like they’ve done at this counter for decades.

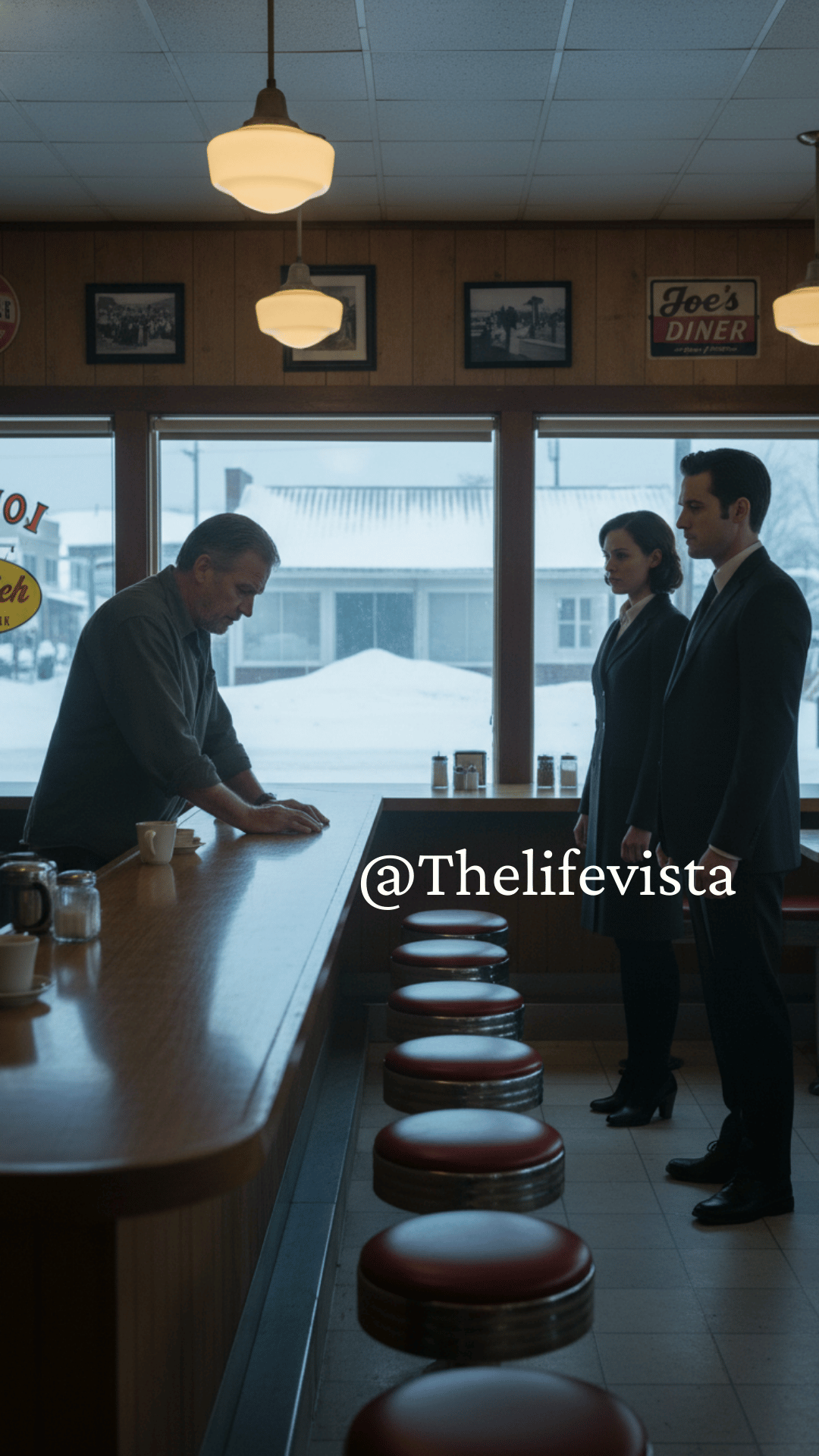

I’m in the back washing dishes when I hear the bell above the door. Be right with you, I call out, drying my hands on a towel. When I come back to the front, there are four people standing by the door. Three of them are in their 30s. Two men and a woman, all dressed nice, like they’ve got somewhere important to be. The fourth is an older man in a suit carrying a briefcase.

Lawyer, probably. You can always tell. They look out of place in my diner. Too polished, too expensive. Not the kind of people who usually stop in Valentine unless they’re lost.

Afternoon, I say, grabbing menus. Sit anywhere you like.

They choose a booth by the window. I bring them water and silverware, pull out my order pad. What can I get you folks?

The woman speaks first. She’s maybe 39. Auburn hair, sharp green eyes, wearing an expensive black blazer. Just coffee for now, please. For all of us.

Coming right up.

I pour four coffees, bring them to the table. They’re all staring at me with this strange expression. Not quite pity, not quite curiosity. Something else.

You folks passing through? I ask, trying to make conversation. Small town instinct. You talk to strangers because everyone else you already know.

Not exactly, one of the men says. He’s younger, maybe 35, dark hair, nervous energy. We came here specifically to see you, Mr. Parker.

I blink. Do I know you?

No, the woman says gently. But we know you. Or we did a long time ago. Mr. Parker, do you remember December 1992, a blizzard? A family that broke down outside your diner.

The world tilts sideways. December 1992, the blizzard. The family with three little kids. Oh my god, the Doyles, I whisper.

The woman’s eyes fill with tears. Yes, I’m Emily Doyle. This is my brother Ryan and my brother Evan. You let us sleep in your diner that night. You fed us. You gave our parents money for car repairs. You saved us.

I have to sit down, pull up a chair from the next table, and just sit because my legs won’t hold me anymore. You were just kids, I say. You were You were tiny. I don’t I don’t understand. How did you find me?

Let me tell you about that night in December 1992. Let me tell you how this started. Let me tell you about the night that changed everything, even though I didn’t know it at the time.

It was December 23rd, 1992, 2 days before Christmas. Linda and I had been running the diner for 13 years by then. We were 38 years old, still young, still hopeful, still trying for kids, even though the doctors kept telling us it probably wasn’t going to happen.

The blizzard hit around 4:00 p.m. Not the gentle snow that drifts down and makes Nebraska look like a Christmas card. The violent kind. The kind that kills people. Wind so strong it knocked out power lines across three counties. Snow so thick you couldn’t see 10 ft in front of you. Temperatures dropping to 15 below zero. Wind chill making it feel like 30 below.

The National Weather Service was calling it the worst blizzard to hit western Nebraska in 20 years. Telling people to stay home, stay off the roads. This was life-threatening weather.

I was supposed to close at 9:00 p.m., but by 6:00 p.m. the roads were impassable. Highway 20 was a skating rink. The parking lot was buried under 2 ft of snow, and it was still coming down.

The last customer left around 6:30. Old Mr. Peterson, who lived three blocks away and insisted he could walk home, even though Linda and I both told him he was crazy, he made it. We checked on him the next day.

After that, nothing. Just me and Linda and the howling wind and snow piling up against the windows like the world was trying to bury us alive.

“We should close,” Linda said around 7. She was wiping down the counter, looking out at the whiteout conditions outside. Nobody’s coming out in this. Anyone with sense is already home.

Yeah, I agreed. I was in the kitchen cleaning the grill, putting away food that would probably spoil before we could use it because the power kept flickering. Let’s clean up and go upstairs.

We lived in the apartment above the diner back then. Still do, actually. 28 steps up the back stairs. Easiest commute in America. Linda used to joke that she could roll out of bed and be at work in under a minute. I timed her once, 47 seconds. She was competitive like that.

We were wiping down tables, turning off lights, getting ready to call it a night when we heard it. A car engine, sputtering, coughing, dying, then silence.

Linda and I stopped, looked at each other across the empty diner. “Did you hear that?” she asked. “Yeah.”

We went to the window, pressed our faces against the glass, trying to see through the snow that was hitting the window so hard it sounded like someone throwing rice at a wedding.

There was a car in the parking lot, old station wagon, maybe mid-80s Ford Country Squire with the fake wood paneling on the sides, covered in snow and ice, exhaust smoke pouring from under the hood. Not good smoke, burning smoke.

The driver’s door opened. A man got out. Then the passenger door. A woman. Then the back doors. Three small children. Five people in the middle of a blizzard.

Car broken down. Middle of nowhere.

Oh no, Linda breathed. Oh, Frank. No.

I was already moving, unlocking the door, stepping out into wind so cold it felt like knives on my face. Get inside. I shouted over the howl of the storm. Come on, get inside now.

They stumbled toward the diner. The man was carrying the youngest child. Couldn’t have been more than 5 years old. Little boy crying and clinging to his father’s neck. The woman had a boy by the hand, maybe seven or eight. A girl, older, 9 or 10 maybe, was walking between them, head down against the wind.

They fell through the door more than walked through it. All five of them covered in snow, shaking from the cold. The kids crying, the parents looking shell shocked and terrified.

Linda slammed the door shut behind them, locked it. The wind was still trying to get in, rattling the windows, making the whole building creak.

“Oh my god,” the woman said. Her teeth were chattering so hard she could barely speak. “Oh my god, thank you. Thank you so much.”

Are you hurt? Linda asked immediately, going into nurse mode. She wasn’t a nurse, but she’d taken classes, first aid, CPR, always wanted to help people. Is anyone injured?

And no, the man stammered. His lips were blue. Actually, blue. Hypothermia blue. Just cold. So cold our car died.

The kids were all crying now. The girl trying to be brave, biting her lip, but tears streaming down her face. The middle boy openly sobbing. The youngest just screaming into his father’s shoulder.

Please, the man said, “Is there a hotel in town somewhere we can stay? We just need to get the kids warm.”

“There’s a motel,” I said. “Valentine Motor Lodge about 2 mi east on Highway 20. But you can’t get there in this. You’d freeze to death before you made it 100 yards.”

The woman made a sound like a wounded animal. What are we going to do? We can’t stay in the car. We’ll die.

Linda didn’t even hesitate. She never did. That was one of the things I loved about her. When something needed to be done, she just did it.

They’re staying here, she announced. Not a question, a fact. Frank, get the space heaters from the back storage room. Get every blanket we have. I’ll make soup.