The pie sat untouched on Ethan Carter’s desk, still warm under a cooling skin of cinnamon steam. Outside his office window, the woman who’d baked it walked away down the long dirt road that led out of Sage Hollow, Wyoming Territory, her shoulders squared like she’d nailed them into place. Ethan had turned her down without tasting a single bite, without asking a single question that mattered. One look at her body, and he’d made his decision the way men made decisions out here: polite, firm, final. Now the ranch hands were laughing about it by the bunkhouse, and Ethan was alone with the smell of apples and butter and something else he couldn’t name. Regret, maybe. Shame, probably. He stared at the pie like it might leap up and call him exactly what he was.

He picked up his fork, broke through the golden crust, and took one bite. The world stopped. If you’re the sort of person who believes pride always wins on the frontier, you might want to read all the way through anyway. Pride wins plenty of battles. It doesn’t always win the war.

The summer of 1883 arrived like punishment. It wasn’t the clean, honest heat of a hearth. It was the kind that made air shimmer over sagebrush and turned the horizon into a wavering lie. It tested cattle, crops, and the people stubborn enough to try surviving both.

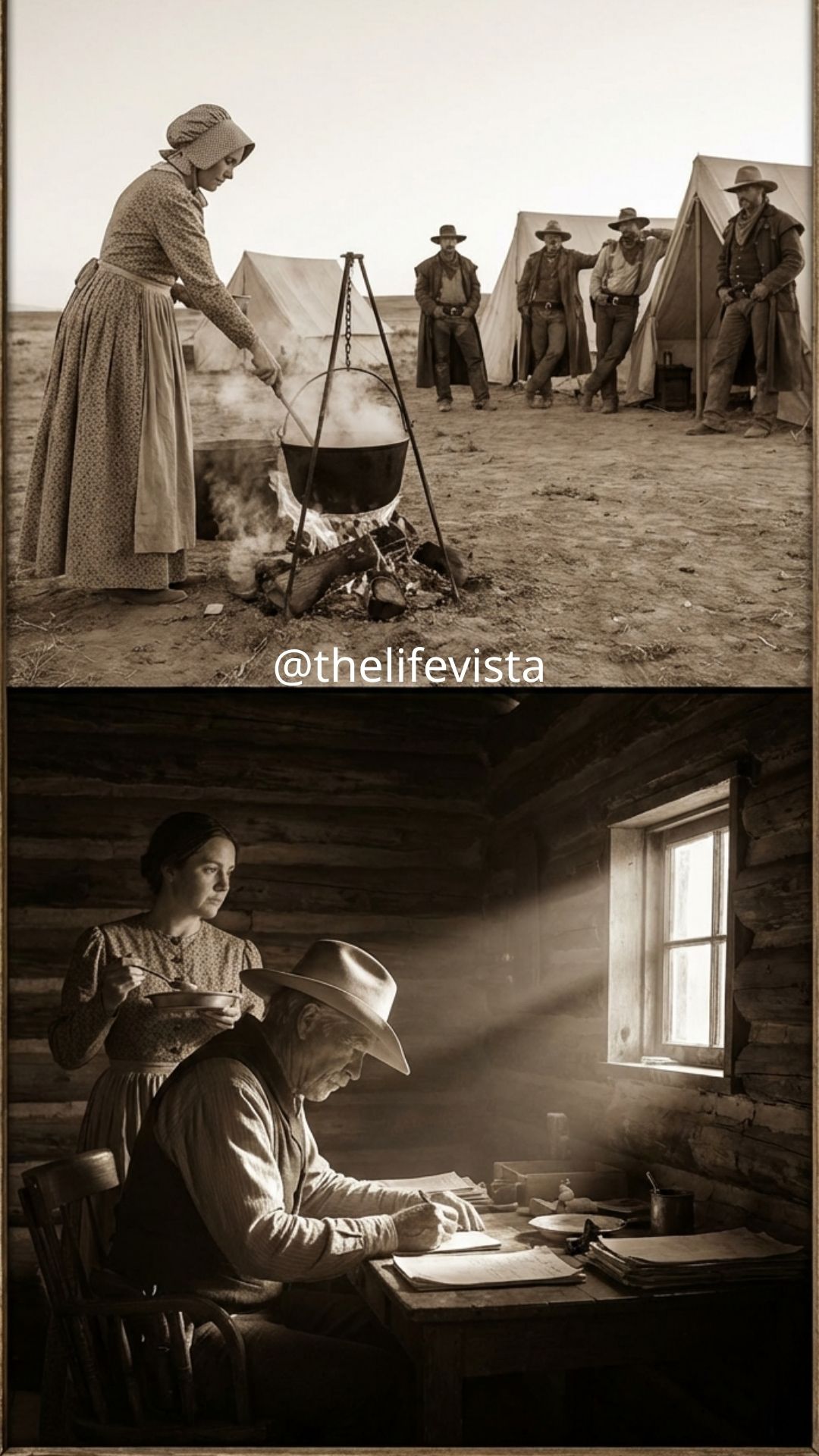

Maya Reynolds stepped off the stagecoach into that heat on a Thursday afternoon with everything she owned tied into a canvas satchel and a carefully wrapped pie balanced in her arms. The driver gave her the kind of look people gave strays and storms, pity mixed with relief that he could keep moving. Sage Hollow was a ranching town, the kind where everyone knew everyone else’s business before breakfast and judged it by noon. False-front buildings stood like cardboard promises, and practical storefronts leaned into the wind: a mercantile, a saloon, a church with peeling white paint, and a land office that doubled as a hiring post for seasonal work. Maya had seen a dozen towns just like it, and each one had taught her the same lesson: her size entered a room before she did.

She walked past the saloon where men loitered in the shade. Conversations died as she passed. She kept her gaze steady, eyes forward, the way you did when you refused to hand strangers the satisfaction of watching you flinch. She could hear their murmurs anyway, the low commentary that traveled like dust. The posting board outside the land office held three notices. A ranch-hand position already filled. A seamstress job that paid in room and board. And, handwritten in sharp block letters: TRAIL COOK NEEDED – CARTER RANCH – SUMMER DRIVE.

The pay was listed as fair. The requirements were simple: experience, reliability, and the ability to handle a crew of thirty men through long days and rough terrain. Maya had all three. She’d cooked in logging camps in Oregon, mining operations in Nevada, and cattle outfits across Montana. She knew how to stretch beans and bacon into something men lined up for twice. She knew Dutch ovens and open fires and wind that could knock a horse sideways. She knew hunger, too, the real kind, and she knew how to keep it from becoming mutiny. She also knew what would happen when she walked into the Carter Ranch office, and she went anyway.

The Carter Ranch office was attached to a small house on the edge of town, neat and well kept with a covered porch and a hitching post out front. A black gelding stood tied there, tail swishing at flies, saddle worn smooth with use. Maya climbed the steps, adjusted her grip on the pie, and knocked. “Come in,” a voice called. It was deep and clipped, the sort of voice that didn’t waste words because it had learned words didn’t fix much.

Inside, the room smelled like leather, old paper, and responsibility. A broad desk dominated the space, crowded with ledgers and shipping notices. Behind it sat a man in his mid-thirties, broad-shouldered and sun-darkened, with the kind of face that had forgotten how to smile. Dark hair cropped short. Jaw shadowed with a day’s stubble. Work shirt with sleeves rolled to his elbows. Hands scarred and capable, braced flat on the desk like he was holding something invisible in place. Ethan Carter looked up. His expression didn’t shift into surprise or disdain. It settled into something flatter than either, and Maya felt her stomach tighten because flatness meant he’d decided before she’d spoken.

“Help you?” he asked. “I’m here about the cook position,” Maya said, keeping her voice level even as her heart picked up speed. “For the summer drive.” His gaze flicked over her once, quick and assessing. She could almost hear the arithmetic happening behind his eyes: weight, heat, distance, endurance. The kind of math men did when they thought they were being practical instead of cruel.

“The position’s demanding,” he said carefully. “Long hours. Rough conditions. Heat like we’re having now, sometimes worse. Men get restless when the work’s hard and the food’s bad.” “I’ve worked trail drives before,” Maya answered. “Logging camps too. I can handle rough conditions.” “I’m sure you can.” His tone was polite, almost kind, which somehow made it sting more. “But I need someone who can keep pace. The drive starts in two weeks. We’ll be moving cattle for nearly three months. It’s hard on everyone.”

Translation: it’s too hard for someone like you.

Maya heard the old familiar click of a door closing inside her chest. She’d heard every version of this conversation. Sometimes they dressed it up as concern for her well-being. Sometimes they just said no outright. Ethan Carter was trying to be decent about it, and that almost made her angrier. “I’m not asking for special consideration,” she said quietly. “Just a fair chance to prove what I can do.”

Something flickered across his face. Discomfort, maybe. Guilt, perhaps. It passed quickly. “I appreciate you coming by, Miss Reynolds.” He stood, signaling the end. “I wish you well, but I don’t think this is the right fit.” The dismissal was gentle. It was also absolute.

Maya swallowed the sharp ache that tried to climb into her throat. She could have argued. Listed her experience. Named men who’d vouched for her skill. But she’d learned that once someone saw her body as a problem, no amount of words would rearrange their mind. So instead, she reached into her satchel and pulled out the pie she’d baked that morning in the boardinghouse kitchen. Simple apple and cinnamon, crust golden and latticed, made with the same care she brought to everything. She set it on his desk, right on top of a shipping manifest.

Ethan stared at it, then at her, brow creasing. “What’s this?” Maya’s voice stayed calm, sharp as a drawn blade. “If my size offends you, Mr. Carter… don’t taste my food.” Then she turned and walked out before he could find a reply.

The boardinghouse where Maya rented a room was run by Mrs. Whitman, a widow with sharp eyes and sharper instincts. She asked too many questions and listened to all the answers anyway. Maya’s room was small but clean, with a narrow bed and a window that overlooked the street. She sat on the edge of the mattress and untied her boots with steady hands. Her chest felt tight, as if the heat had found a way inside her ribs. She’d known this would happen. She always knew. Still, some stubborn part of her kept hoping that one day someone would look past the surface and see what she could actually do.

A knock came at the door. “Supper’s in an hour,” Mrs. Whitman called through the wood. “Are you eating downstairs?” “I’m not hungry,” Maya answered automatically, but hunger wasn’t the only thing that brought you to a table. Loneliness had sharp teeth too, so she went downstairs anyway.

The dining room was crowded: ranch hands from nearby outfits, a traveling salesman, and a pair of surveyors passing through. Maya took a seat at the far end, kept her eyes on her plate while conversation flowed around her like river water. “Heard Carter’s still lookin’ for a trail cook,” a ranch hand said, shoveling beans into his mouth. “Cutting it close.” “He turned down some woman today,” another said with a smirk. “Big gal thought she could handle a crew.” Laughter rippled down the table, and Maya’s fork stilled against her plate.

“Probably for the best,” someone else added. “Carter’s got enough to worry about without some gal slowing things down.” “She baked him a pie though,” the salesman said, grinning. “Heard about that? Bold move.” “Bold or desperate?” another muttered. Mrs. Whitman appeared at Maya’s elbow with a coffee pot, expression tight. “More coffee, dear?” “No thank you.” Maya stood, appetite gone in a way food couldn’t fix. “I think I’ll turn in early.”

Upstairs, she sat by the window and watched Sage Hollow settle into the evening. Somewhere, Ethan Carter was finishing his own supper. The pie she’d left him still sat on his desk untouched, and she told herself it didn’t matter. The ache in her chest disagreed. The lesson she’d learned in too many towns pressed in around her: people will call their judgment “common sense” to avoid admitting it’s fear, and the only way to keep your soul intact is to refuse to shrink for anyone who benefits from you being smaller.

Ethan didn’t go home until well after dark. He spent the evening hunched over supply lists and inventory, trying to ignore the pie. It sat there like an accusation, filling the small office with its scent until he couldn’t think around it. Cinnamon, apples, warm crust. It smelled like something he’d once had and hadn’t been able to keep. Finally, when the lamplight burned low and his eyes blurred from ledger lines, he gave in. He pulled the pie toward him, cut a small slice, and lifted it to his mouth.

The first bite stopped him cold. The crust was perfect. Flaky, buttery, sweet enough to balance the tart apples. The filling was spiced with cinnamon and something deeper he couldn’t name, a note that made the whole thing feel… intentional. Like someone had cooked with a memory in mind. He took another bite, slower, and suddenly he wasn’t in his office anymore. He was in his kitchen three years ago, watching his wife Claire roll dough on the counter. Flour dusted her hands, her apron, her cheek. She’d been laughing about something. He couldn’t remember what. But he remembered the smell. This smell. Warmth and safety and a life that felt whole.

Then she was gone. The kitchen went quiet. The house went hollow. And Ethan had become the man behind the desk who thought “practical” was the same as “right.” He set the fork down and pressed his palms against the desk. His throat tightened like it wanted to confess something his pride didn’t. He’d judged Maya Reynolds without giving her a chance. Without even asking her name properly. He’d looked at her body and decided the rest of her didn’t matter. Shame crawled up his spine, hot and familiar. Claire’s voice rose in his memory, not as a ghost, but as a truth he’d ignored: People aren’t what you see first.

He pushed back from the desk so hard the chair scraped. It was late, too late to fix it tonight. But in the morning, he’d find Maya Reynolds and do what he should’ve done from the start. He’d ask for a second chance.

Dawn came early, pale gold promising another scorching day. Ethan saddled his horse before the sun cleared the horizon and rode into town while streets were still quiet. He found Maya near the edge of Sage Hollow at a roadside stand selling biscuits and coffee to early travelers. A hand-painted sign read: HOME COOKING. FAIR PRICES. A few men stood nearby eating, their voices low. The smell of fresh bread hung in the air like a dare.

Ethan dismounted, tied his horse, and walked over slowly. He took off his hat when he reached her. Maya saw him coming and went still. She didn’t look away. “Mr. Carter,” she said evenly. “Miss Reynolds.” He stopped a respectful distance back, aware the men nearby were watching. “I owe you an apology.” Her eyebrows rose, just slightly, and she said nothing.

“I judged you yesterday without giving you a fair chance,” Ethan continued. The words tasted bitter but necessary. “That was wrong. I tasted your pie last night, and…” He searched for something honest that wasn’t dramatic. “It reminded me I’ve been acting like a man I don’t want to be.” Maya folded her arms. Her expression stayed guarded, but her eyes sharpened. “Why now?” she asked, voice quiet as coals. “What changed?” Ethan met her gaze and let her see the crack in him. “I remembered what it feels like to be wrong.”

Silence stretched. A horse stamped. One of the men cleared his throat like he wanted the moment to hurry up. Ethan drew in a breath. “I’d like to offer you the position. If you’re still interested.” Maya studied him as if weighing a sack of flour, judging whether it was full or cut with grit. Finally, she nodded once. “I’ll take the job. But I don’t work for pity, Mr. Carter. I work for respect. If you can’t give me that, we’re done before we start.” “You’ll have it,” Ethan said, and meant it with a steadiness that surprised him. “You have my word.”

Maya held out her hand. Her grip was firm and calloused. “Then we have an agreement.” As Ethan rode back toward his ranch, the morning sun climbing higher, he felt something shift inside him. Not hope exactly. Hope was a tender thing, and he’d treated tender things like liabilities since Claire died, but maybe it was the first crack in the armor. Back at the roadside stand, Maya packed her table and allowed herself the smallest smile. She’d been turned away a hundred times. This time, someone had come back.

The Carter Ranch sat ten miles outside Sage Hollow, sprawling across a valley bordered by pine-covered hills and a creek that ran cold and clear even in summer. It wasn’t pretty. It was practical: main house, bunkhouse, barn, corrals, and the cookhouse near the men’s quarters like a small outpost of warmth. When Maya arrived two days later in the back of a supply wagon, ranch hands stopped what they were doing to stare. She climbed down with her satchel and surveyed the place she’d be calling home for the next three months.

Ethan approached from the barn, wiping his hands on a rag. “Miss Reynolds. Welcome.” “Thank you.” She nodded toward the cookhouse. “Mind if I take a look?” “Go ahead. If you need anything, let me know.” The cookhouse smelled of old smoke and grease. Cast-iron stove, long worktable, shelves lined with tin plates, pantry stocked with basics: flour, beans, salt pork, dried apples. Not fancy. Functional. Maya set down her satchel and rolled up her sleeves.

By noon she’d scrubbed the stove, reorganized the pantry, started a sourdough starter, and made a list of what she’d need on the drive. By evening, she prepared her first meal for the crew: beef stew with vegetables, fresh biscuits, and dried apple cobbler. When the men filed in, their talk died as they saw her behind the serving line. Ethan was the first through. “Smells good.” “Thank you.” Maya filled his plate without looking up.

One by one, the men stepped forward. Some offered polite nods. Others muttered thanks. A few said nothing at all. Maya felt their scrutiny the way you felt heat off a stove. She worked anyway, and then they tasted the food. Silence fell, not hostile now, but stunned. An older hand named Walt looked up from his bowl, eyes wide. “Ma’am,” he said, voice reverent as church, “this is the best stew I’ve had in ten years.” A few men nodded without shame. The room loosened by a single degree. Maya breathed out, slow. It was a start.

The first week passed in a blur of heat and hard work. Maya rose before dawn, cooked three meals a day for thirty men, and cleaned long after the sun had dropped behind the hills. Her hands blistered, then calloused. Her back ached from bending over the stove. She didn’t complain because complaining wasn’t currency that bought respect. Some men warmed to her. Walt started offering to chop wood and carry water without being asked. A young hand named Cole lingered after meals, shyly asking how she made biscuits so light they didn’t sit like rocks.

But not everyone softened. A lean man named Travis watched her with open skepticism. He didn’t say much at first, but his silence had teeth. He listened to the other men praise her food the way a man listened to a rumor about his own defeat. Late one evening, after supper, Ethan stopped by the cookhouse while Maya washed dishes. “Need any help?” he asked from the doorway. “I’m fine,” she said, then watched him step in anyway.

He picked up a towel and began drying plates in a quiet rhythm with her washing. For a few minutes, there was only a splash of water and a clink of tin. “The men are eating better than they have in years,” Ethan said finally. “I wanted you to know that.” “They’re easy to please,” Maya replied. “Good ingredients. Honest cooking.” “It’s more than that.” He set down a plate, looked at her properly. “You brought something back to this place. Something I didn’t realize we’d lost.” Maya’s hands were still in the water. “What’s that?” “A sense of home.”

The words hung between them, heavier than they should’ve been for a cookhouse conversation. Maya didn’t trust them, not because she thought he lied, but because she knew how quickly people changed when other people were watching. She dried her hands on her apron. “Thank you for the second chance, Mr. Carter.” “Ethan,” he corrected quietly. “And you’ve earned it.” When he left, Maya stood alone under the dim lamplight, heart beating faster than it should. For the first time in a long time, she let herself imagine what it might feel like to stay.

The drive began on a Tuesday morning before the sky had decided what color it wanted to be. Maya had been awake since three, loading the chuck wagon by lantern light, checking straps, rechecking inventory, making sure every barrel and sack was where her hands could find it in darkness. The cattle moved like a river under the guidance of outriders. The sound of three thousand hooves made Maya’s chest tighten with something between fear and exhilaration. The trail wasn’t just work. It was a proving ground. It was where men decided what was true about you and never admitted later if they’d been wrong.

Walt approached, weathered face creased with concern. “You got everything you need?” “Everything I can fit.” Maya climbed up to the seat, took the reins. “I’ll follow the herd at a distance. Set camp where Ethan says.” “He’ll pick good spots. Always does.” Walt hesitated. “Don’t let the boys give you grief. They’re good men, mostly. Just… ornery when they’re tired.” “I can handle ornery,” Maya said. Walt touched his hat brim. “If anyone crosses a line, you tell me. Or better, tell Ethan.” Maya nodded without promising. She’d fought her own battles all her life.

The wagon lurched forward. Behind her, the ranch buildings shrank and disappeared as the road curved into open country. For the first few hours, it was almost peaceful. Then the sun climbed, and peace became heat. Dust rose from cattle and horses, coating everything in grit. Maya tied a bandana over her nose and kept the mules moving, mind already mapping meals.

At midday, Ethan chose a stop near a shallow creek. Maya had a fire going before most men had unsaddled. Beans, bacon, cornbread, coffee strong enough to peel paint. Heads turned toward the chuck wagon as the smell spread. Cole approached first. “Miss Reynolds, can I help?” “Water,” Maya said. “Fill the coffee pot and wash the basin.” He hurried to obey like a boy grateful for a purpose.

When Maya rang the triangle for food, the line formed fast. Men ate with the quiet hunger of people who respected the clock and the plate. Ethan came through last, took his portion, met her eyes. “Holding up?” he asked. “Fine,” Maya said. “It’ll get harder.” “I know,” he replied, and something in his tone made it sound less like a warning and more like a vow that he’d be there when it did.

The second day brought a heatwave that pressed down like a hand. By noon, Maya found her supplies wrong. A wheel of cheese is gone. Ten pounds of dried beef missing. The kind of loss that wasn’t just inconvenient, it was dangerous. She found Ethan watering his horse. “We have a problem.” He read the tension immediately. “What kind?” “Someone raided my stores last night.” Ethan’s jaw tightened. “You’re sure?” “I inventory every night,” Maya said. “The theft happened after.”

Within minutes, Ethan gathered the men. He didn’t speak in circles. “Someone stole from the chuck wagon,” he said. “Food meant to feed all of us. That isn’t just theft. It endangers every man here.” Silence. Shifting boots. Eyes sliding sideways. “I don’t care who did it,” Ethan continued, voice low and hard. “But it won’t happen again. If I find out who’s been helping themselves, they’re off this drive and walking back to Sage Hollow.” Murmurs of agreement followed, but Maya saw the looks too: resentment in some, disbelief in others, and something uglier in a few that said this is what happens when you hire someone who doesn’t belong.

The afternoon nearly killed a drover named Eli. He slumped from his horse like a puppet cut loose. Heat exhaustion, maybe worse. Maya ran with her water bucket, taking command without asking permission. “Shade,” she ordered. “Now. Boots off. Cool his neck and forehead.” A man scoffed at the idea of whiskey for cooling. Maya snapped, “Not to drink. To cool the skin. Move.” They moved. Twenty minutes later Eli’s eyes focused again. He whispered, ashamed, “I thought I could push through.” “That’s how men die,” Maya said, gentler than her words sounded. “Listen to your body out here.”

Ethan crouched beside her. “Will he be all right?” “If he rests. He can’t ride for a day, maybe two.” Maya glanced at the chuck wagon. “He can ride with me.” Complaints started. The wagon wasn’t for passengers. Weight mattered. Maya stared until the complaints died. “He can ride with me,” she repeated, and this time it wasn’t a suggestion. Ethan stood and faced the crew. “Anyone else feeling poorly, speak now. I won’t have stubbornness burying people.” A couple men admitted dizziness. Ethan reassigned them to lighter duty. That night, when Maya served dinner, some men looked at her with new respect. Others looked like she’d embarrassed them by being competent in a way they couldn’t ignore. Travis looked like he’d swallowed a nail.

Supplies continued disappearing in small amounts. A little flour here. A pinch of coffee there. Never enough to point cleanly. Always enough to add up. Maya slept lighter, woke at every sound, but the thief stayed ahead. Then sabotage turned bold. One morning, the horse line broke. A dozen horses scattered. Several steers bolted. Men shouted, ran, cursed. In the middle of the chaos, Maya found the water barrels upended, stoppers pulled, every drop soaking into the ground.

She stood staring at the empty barrels and felt something inside her go cold. Cole ran up, breathless. “Miss Reynolds, what do we do?” Maya forced her voice steady because panic was contagious. “Get every container we have. Canteens, pots, buckets. Anything that holds water. We’re going back to the creek.” “But the herd…” “Men and horses can’t wait,” Maya said, already hitching the mules. “We leave in ten minutes.”

Walt, face grim, handed her his canteen. “This isn’t a coincidence,” he muttered. “Upended water and a broken horse line. You think sabotage?” “I think someone wants me to fail,” Maya said quietly. The trip back to the creek took two hours, prairie exposed and unforgiving. They filled every container, secured barrels tight. Cole asked softly, “Why do you do this? The hard work… the disrespect… proving yourself every day?”

Maya tightened a strap until it bit into leather. “Because I’m good at it,” she said. “And because the moment I stop, the moment I choose easier just because it’s easier, I’m agreeing with men like Travis. I won’t give them that satisfaction.” Cole nodded like the answer landed somewhere deep. “For what it’s worth, I think you’re the bravest person I’ve ever met.” Maya snorted, tired. “Bravery and stubbornness look mighty similar from the outside.”

They returned to camp with water and exhaustion. Ethan watched Maya like he was seeing her for the first time and hating himself for not seeing sooner. That evening, after dinner, Ethan gathered the crew again, voice cutting through night air. “We’ve had incidents that aren’t accidents,” he said. “Missing supplies. Dumped water. Broken horse line. Someone is sabotaging this drive.”

Travis spoke from the back, voice slick. “You sure it’s sabotage, boss? Maybe it’s just someone who can’t handle the job making excuses.” The implication turned the air poisonous. Ethan moved toward Travis slowly, like a storm deciding where to break. “You want to make an accusation,” he said softly, “make it plain. Say it so everyone hears.” Travis’s courage wavered. “I’m just saying maybe we’re looking at it wrong.”

“No,” Ethan said, voice colder than creek water in winter. “You’re saying Miss Reynolds is incompetent or a liar. And you’re saying it because tearing her down is easier than admitting she’s doing better than you expected.” Ethan’s gaze swept the men. “Anyone caught stealing or tampering will be sent back on foot with no pay. I don’t care if you’ve worked for me for ten years or ten days.” Murmurs of assent rose, stronger this time, because fear makes honesty louder.

Later, when Maya banked the fire, Derek stepped out of the dark like he’d been made of it. “It’s Travis,” he said. “I saw him messing with the horse line. Didn’t realize until after. And I’d bet my wages he dumped the water. He’s not alone either.” Ice slid down Maya’s spine. “What do I do?” Derek’s expression softened, barely. “You keep doing what you do. Stay alert. Get us to the trading post in three days. Once we resupply, his argument dies.” Three days, Maya told herself. She could do three days.

On the morning they were meant to reach the trading post, Maya woke to find her Dutch oven missing. The heavy cast iron pot was essential. Without it, she couldn’t bake bread, couldn’t slow cook stews, couldn’t do half the work that turned trail food into something men could stomach. She searched the wagon twice, then the ground around camp. Nothing.

Ethan found her standing rigid by the chuck wagon, hands shaking with rage so pure it scared her. “What happened?” “The Dutch oven.” Maya’s voice went flat. “It’s gone.” Ethan’s face set. “Derek. Where’s Travis?” Travis arrived with two men, Logan and Bryce, all belligerence and nerves. Ethan didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t have to. “Empty your saddle bags,” he said. Logan and Bryce complied. Travis stalled. “That’s an order,” Ethan repeated.

When Travis finally upended his bag, a piece of flour sack cloth fell out. Maya recognized it instantly. She’d marked every sack with a pencil. “That’s from the chuck wagon,” Maya said, pointing at her own inventory mark. Silence hit like a hammer. Ethan’s voice turned lethal. “Last chance, Travis. Tell me where the Dutch oven is.” “I don’t have your damn pot,” Travis snapped, then tried to pivot. “A little extra food here and there isn’t theft. It’s making sure we get our fair share. She was holding back the good stuff.”

“She was rationing so we don’t starve,” Ethan said, disgust heavy in every word. “Get your things. You’re done.” Travis jabbed a finger toward Maya. “This is because of her. You’re choosing her over men who’ve worked for you for years.” “I’m choosing competence over sabotage,” Ethan said, stepping closer. “Character over cruelty.”

Travis spat the truth he’d been carrying like a weapon. “She doesn’t belong here. A woman like that doing men’s work. It ain’t natural.” Ethan’s eyes went flint. “What’s not natural is a man so threatened by a woman’s competence he has to undermine her to feel like a man.” Travis’s face twisted, but he saw something in Ethan’s expression that made him back down. He stalked off to pack.

Derek searched Travis’s gear. No Dutch oven. “Then he hid it,” Derek muttered, “or someone else took it.” Ethan exhaled hard. “Doesn’t matter now. We push to the trading post.” Maya turned away to start breakfast without her oven, making do with fried cornmeal cakes and weak coffee. She didn’t cry. She didn’t break. Not where anyone could see, because on the frontier, people watched for breaking the way wolves watched for limping.

Two hours into the day, the creek they needed to cross had flooded from storms upstream. The ford was a churning brown torrent. Too dangerous for cattle. Too dangerous for horses. Walt rode back, face grim. “We’ve got to find another crossing. Could add a full day.” Maya’s stomach sank. Her supplies were down to nearly nothing. “How much food do we have left?” she asked Ethan, though she already knew.

“Enough for one more meal,” Maya said when he didn’t answer fast enough. “Maybe two if I stretch it to cruelty.” Ethan stared at the water like he could intimidate it into lowering. Then he turned back to camp. “I’m taking men upstream to scout.” They returned hours later with bad news: no safe crossing for ten miles, creek still rising.

And then Ethan looked west. A wall of dark clouds built on the horizon. Lightning flickered inside them like trapped fire. “We’ve got three hours,” Ethan said. “Before that hits.” Cole’s voice cracked. “What do we do?” Ethan looked at Maya, eyes steady, asking the same question he’d asked before when things got impossible. “What do you need?”

Maya’s first thought was a miracle. Her second thought was that miracles didn’t cook meals. She forced her mind into motion. “I need whatever game we can get. Rabbits, birds, anything. And I need every man who knows edible plants to gather what they can before the storm hits.” Ethan straightened and raised his voice. “Anyone who can shoot, you’re hunting. Anyone who can forage, you’re with Miss Reynolds. We’ve got three hours to gather enough food to get through the next two days. Move!” Camp exploded into purposeful chaos.

Maya led men along the creek bank, pointing out cattail roots, lamb’s quarters, wild onions, and small tart plums. “Dig these up. Fill sacks. Don’t guess. Ask if you’re unsure,” she ordered, voice sharp with urgency. Cole stayed close, learning with wide-eyed focus. “How do you know all this?” “An old cook in Montana taught me,” Maya said, yanking up a handful of onions. “She got snowed in one winter with no supplies. She taught me food is everywhere if you know where to look. Towns make people forget that.”

Hunters returned with rabbits, sage grouse, and a young turkey. It wasn’t much for thirty men, but it was something. Maya worked like her hands weren’t attached to her body, plucking birds, butchering rabbits, boiling cattail roots, building a stew out of prairie scraps and stubborn will.

Then the storm hit. Rain turned to sheets. Wind whipped tents like angry hands. Loose gear tumbled. Lightning split the sky in jagged white scars. Ethan appeared beside Maya, shouting over the storm. “Get under cover! You’re going to get struck!” “Food’s not ready!” Maya shouted back, shielding the fire with her own body. “These men need to eat!”

Ethan stared at her for one heartbeat, then made a decision that mattered more than any speech he’d given. He stayed beside her. He took canvas, helped rig shelter, helped build a windbreak, helped keep the fire alive. Other men saw and joined. Walt hauled crates. Derek hammered stakes. Cole held the canvas steady with shaking hands.

When the triangle finally rang, the men came through rain without complaint, lined up to eat stew that tasted like prairie and desperation and survival. No one mocked the cattail roots. No one complained about wild turkey. They ate with the gratitude of people who understood how close hunger had been.

By dawn, the creek had dropped enough to attempt a crossing. It was tense, the cattle balking at the swift current, but the crew moved together now like a single organism, driven by shared adversity instead of division. Midmorning, they crested a rise and saw the trading post ahead: rough buildings that looked like salvation. Maya’s legs nearly gave out when she climbed down from the wagon.

The proprietor squinted at her mud-caked, exhausted state. “Heard you folks had trouble.” “You could say that.” Maya handed over her list. “I need everything on it. And a new Dutch oven if you’ve got one.” The man jerked a thumb toward the back. “Got one. Heavy as sin.” “I’ll take it.”

While supplies were gathered, Maya sat on the porch with a cup of real coffee, hands wrapped around warmth like it was a promise. Ethan sat beside her, quiet for a long time. Then he said the words that landed deeper than praise. “You saved this drive.” “We saved it,” Maya corrected, because she’d learned not to carry victories alone. They got too heavy.

Ethan nodded. “When we get back to Sage Hollow, I’m offering you a permanent position. Ranch cooks year-round. Fair pay. A place of your own on the property.” Maya’s breath caught. For a moment, the girl who’d been turned away a hundred times stood inside her, staring in disbelief. Then Maya Reynolds, the woman who’d boiled cattails in a storm to feed thirty men, answered simply. “I accept.” Ethan’s expression softened, relief and something else moving behind his eyes. “Thank you,” he said quietly. “For giving me a second chance to do the right thing.” Maya looked out at the trading post yard, at men laughing for the first time in days, at the chuck wagon being restocked, at the Dutch oven returned to its rightful place in her world. “We both got second chances,” she said. “Seems only fair we make the most of them.”

The first snow came early that year, dusting the Mercer Ranch in clean white and turning the valley quiet enough to hear the creek sing under ice. Maya Reynolds stood in the cookhouse doorway with her new recipe book open on the table behind her, watching men move through the yard with steady purpose instead of swagger, because the season on the trail had burned something honest into all of them. Ethan Mercer walked up the path carrying a split armful of firewood, set it down without a word, and for a moment they simply looked at each other like people who’d survived the same storm and recognized the shape of it in another face. “I can’t give you back the years you were turned away,” he said at last, voice low, “but I can give you what’s mine to give—pay that’s fair, work that’s real, and a home that doesn’t ask you to shrink.” Maya closed the distance between them, not as a favor and not as a surrender, but as a choice she’d earned with heat and hunger and grit under her nails. “Then we do it right,” she replied, eyes steady. “No pretending, no apologies that don’t turn into action, and no measuring people by what makes others comfortable.” Ethan nodded like he understood the rule was a promise, and the ranch behind him—once just fences and duty and ghosts—felt, for the first time since his loss, like something living. Inside, the dinner bell rang, calling everyone in, and Maya turned back to the stove with a calm that didn’t need permission; outside, Ethan followed, and the town could talk itself hoarse if it wanted, because the truth was already written in the only ledger that mattered: a table kept full, a door left open, and two people choosing, day after day, to build a life no one could buy, steal, or shame away.

The end.