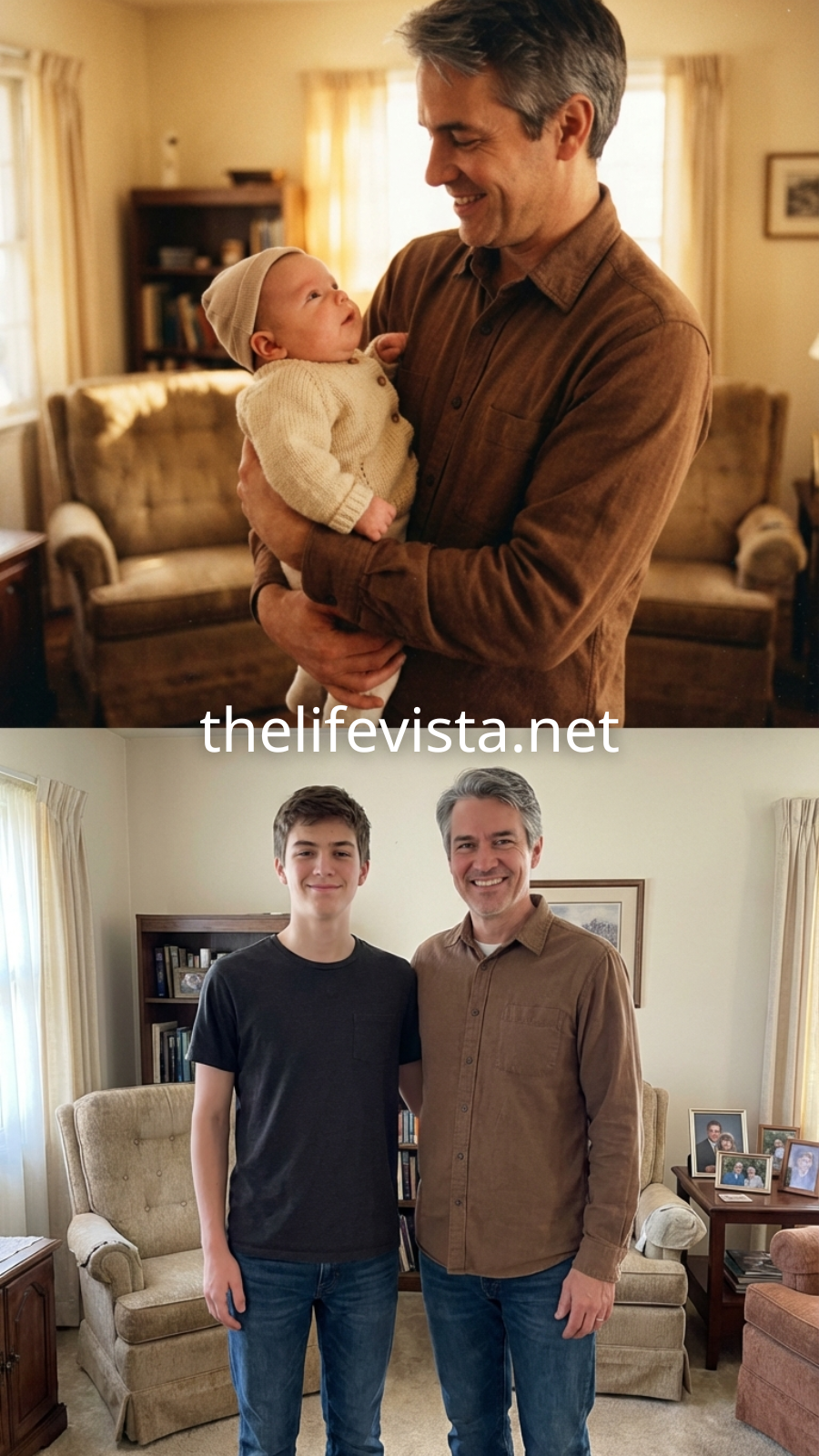

Thirteen years ago, I became a father to a little girl who lost everything in a single, devastating night. I wasn’t married, I wasn’t prepared, and I definitely wasn’t searching for a family. But when those wide, terrified eyes met mine, I knew I was finished. I reshaped my entire life around her and loved her as if she were my own flesh and blood.

Then, six months ago, I believed I’d finally found someone to share that life with. But my girlfriend revealed something that shook me to my core, forcing me to choose between the woman I thought I’d marry and the daughter I had raised from the wreckage of tragedy.

The Night the World Shattered Inside the ER

The night Avery entered my life, I was twenty-six years old, working the overnight shift in the ER of a busy Chicago hospital. I’d finished medical school just six months earlier, still inexperienced, still learning how to stay steady when chaos exploded all around me. I lived on caffeine and adrenaline, convinced I’d already seen the worst of it.

I hadn’t.

Just after midnight, the automatic doors flew open.

A multi-vehicle collision on the interstate. Black ice had turned I-90 into a death trap. Paramedics rushed in, shouting vitals, boots squealing against the linoleum. The air instantly filled with the metallic scent of blood mixed with harsh antiseptic.

Two stretchers passed me. White sheets pulled over faces. The silence beneath those sheets was heavier than the screaming trauma bay.

Then came a third gurney.

A three-year-old girl.

She wasn’t crying. That was what terrified me most. Children cry when they’re hurt; silence usually means shock or something far worse. She sat amid the chaos, covered in soot and shallow scrapes, clutching a stuffed rabbit by one ear so tightly her knuckles had gone white. Her large hazel eyes darted around the room, scanning nurse after doctor, searching for something familiar in a world that had just collapsed.

Her parents were already gone before the ambulance arrived. The paramedics told me quietly—blunt force trauma, instantaneous. They were gone, and she was all that remained of their world.

I wasn’t supposed to stay with her. My role was to assess, treat, and move on. I checked her vitals—elevated heart rate but stable. Pupils reactive. Ultrasound clear. Physically, she was astonishingly unharmed. Emotionally, she was shattered.

When the nurses tried to move her to a quieter room while social services was contacted, she panicked. It wasn’t a tantrum. It was raw terror. She latched onto my arm with both hands and refused to let go. Her grip was so tight I could feel her pulse racing through her fingers like a trapped bird.

“I’m Avery. I’m scared. Please don’t leave me. Please…” she whispered again and again, like a prayer, like if she stopped, she might disappear too.

I looked at Sarah, the charge nurse. She met my eyes and nodded gently. “Go. I’ll cover your bay for twenty minutes.”

I stayed.

I ignored my pager—an eternity in an ER. I found her apple juice in a pediatric sippy cup. I wiped soot from her cheek with a warm cloth. I read her a battered picture book about a bear who lost his way home, and she made me read it three more times because the ending was happy, and maybe she needed to hear that happy endings still existed.

When she touched my hospital badge, traced my photo with trembling fingers, and said, “You’re the good one here,” I had to step into the supply closet just to breathe. I slid down the wall among boxes of saline and gauze and cried for three solid minutes. Then I washed my face, put my mask back on, and went back out.

The Accidental Father Takes His First Step

Social services arrived the following morning. Mrs. Gable was the caseworker—kind eyes, tired soul, clipboard heavy with decisions that shaped children’s lives. She knelt and asked Avery if she knew any family… grandparents, aunts, uncles, anyone.

Avery shook her head. She didn’t know phone numbers or addresses. She knew her rabbit was named Mr. Hopps. She knew her curtains were pink with butterflies. She knew her daddy sang silly monkey songs in the car.

She also knew she wanted me.

Every time I stepped toward the door to chart a patient, panic flashed across her face—pure abandonment. Like her brain had learned in one terrible instant that people leave, and sometimes they never return.

Mrs. Gable pulled me into the hallway beneath flickering fluorescent lights. “She’ll be placed in temporary foster care. There’s no immediate family available. We’ll begin searching, but right now, she’s alone.”

I looked through the glass. Avery was watching the door, waiting for me.

And I heard myself say, “Can I take her? Just for tonight. Until you sort things out.”

The words escaped before logic caught up.

“Are you married?” Mrs. Gable asked.

“No.”

“You’re single, work nights, barely out of school, live alone, and have zero experience,” she said flatly.

“I know.”

“This isn’t babysitting,” she warned. “Foster care is trauma. It’s night terrors. Courtrooms.”

“I know that too,” I said, inhaling deeply. “But she screams every time I let go of her hand. I can’t watch a child who lost everything be carried off by strangers tonight. I have vacation days. I’ll take leave. Just… don’t put her in the system today.”

I couldn’t break the promise I hadn’t known I made when she grabbed my arm.

Mrs. Gable studied me for a long moment, weighing my character against policy. Finally, she sighed. “I can authorize an emergency placement for seventy-two hours due to attachment and your medical background. But if you want this to continue, you’ll need certification fast.”

I signed paperwork right there in the hallway. Called out sick for three days. Buckled her into a borrowed car seat and drove her home.

Learning to Swim Where There Is No Shallow End

One night turned into a week. A week became months.

The first month was exhausting in a way residency never was. Avery had night terrors. She woke screaming for her mother, thrashing in the toddler bed I’d hastily assembled. I’d sit on the floor, rubbing her back, whispering that she was safe—even when I knew she didn’t feel it.

I learned to cook real food. I learned “no” was a complete sentence. I learned grief in children comes in waves—sometimes quiet withdrawal, sometimes explosive meltdowns over the wrong sippy cup.

I fought for her in court. When distant relatives appeared—a cousin who wanted insurance money but not the child—I hired a lawyer I couldn’t afford. I went into debt. Worked extra shifts. Stood before a judge and argued that love could outweigh blood.

The first time Avery called me “Daddy,” we were in the cereal aisle.

“Daddy, can we get the dinosaur one?”

She froze instantly, box hovering in her hands, eyes wide—waiting for correction.

I knelt to her level, throat tight. “You can call me that if you want, sweetheart. Only if you want. I’m here. I’m not leaving.”

Her face crumpled. She nodded. “Okay. Daddy.”

I adopted her six months later. Courthouse. White dress she chose. Ice cream for dinner.

I built my life around her. Learned to braid hair badly. Memorized Disney princesses and held firm opinions about Mulan. Sat through ballet recitals where she waved at me the entire time.

I switched to a daytime schedule. Started a college fund. We weren’t wealthy—but she never wondered if she was loved.

I showed up. Always.

The Teenager and the Woman Who Didn’t Belong

She grew into a sharp, funny, stubborn teenager with a resilience that amazed me. She carried her trauma as empathy.

By sixteen, she had my sarcasm and her mother’s eyes. Photos of her parents stayed on her dresser. We honored their birthdays. I never replaced them—I just protected their memory.

“Dad, don’t freak out, but I got a B+,” she’d say.

“That’s good.”

“No, it’s tragic.”

She was my whole heart.

I didn’t date much. Loss makes you careful. A few women came and went. None could handle our bond.

Then I met Marisa.

She worked hospital admin. Polished. Smart. Dry humor. At first, she was great with Avery.

Then the comments started.

Then things went missing.

Then the accusation came.

And when Avery told me her gray hoodie—the one in the video—had been missing for two days, everything inside me went cold.