Part I — Idle

The boy pressed his ear to my idling Harley like it was a heartbeat—barefoot on hot Ohio asphalt, eyes closed, counting breaths—and the whole parking lot forgot how to breathe.

Phones hung midair. Late sun threw orange bars across the concrete, pulsing off chrome and glass. A sedan had swung too wide around the pumps at my two-bay garage and rolled away with the bass still thumping. It didn’t come back. The kid stayed.

Skinny. Eleven, maybe. Denim jacket two sizes too big. A red metal lunchbox dangling from one hand; something tin inside rattled like rain. He didn’t cry. He laid his cheek against my Road King’s tank and breathed in the fumes like bakery steam.

“Hey, buddy,” I said, soft as I could. “That metal’s warm.”

Name’s Ray Delgado—folks at the hall call me Steel. Thirty years as an ironworker. Widower. Knuckles like old bolts. These days I run a neighborhood garage that still writes estimates on a clipboard. I’ve watched all kinds of hard days sputter in on a flatbed. I’d never seen quiet like that boy’s quiet.

A pickup cracked the throttle on the road. The kid barely flinched: a ripple through the shoulder, a tremor in the jaw. He pressed harder into the tank. The motor sat in a sweet eight-hundred-RPM idle, even as a metronome. My hand hovered over the grip, ready to ease it down.

A man in a polo lowered his phone. “Sir, is he with you?”

“He is now,” I said.

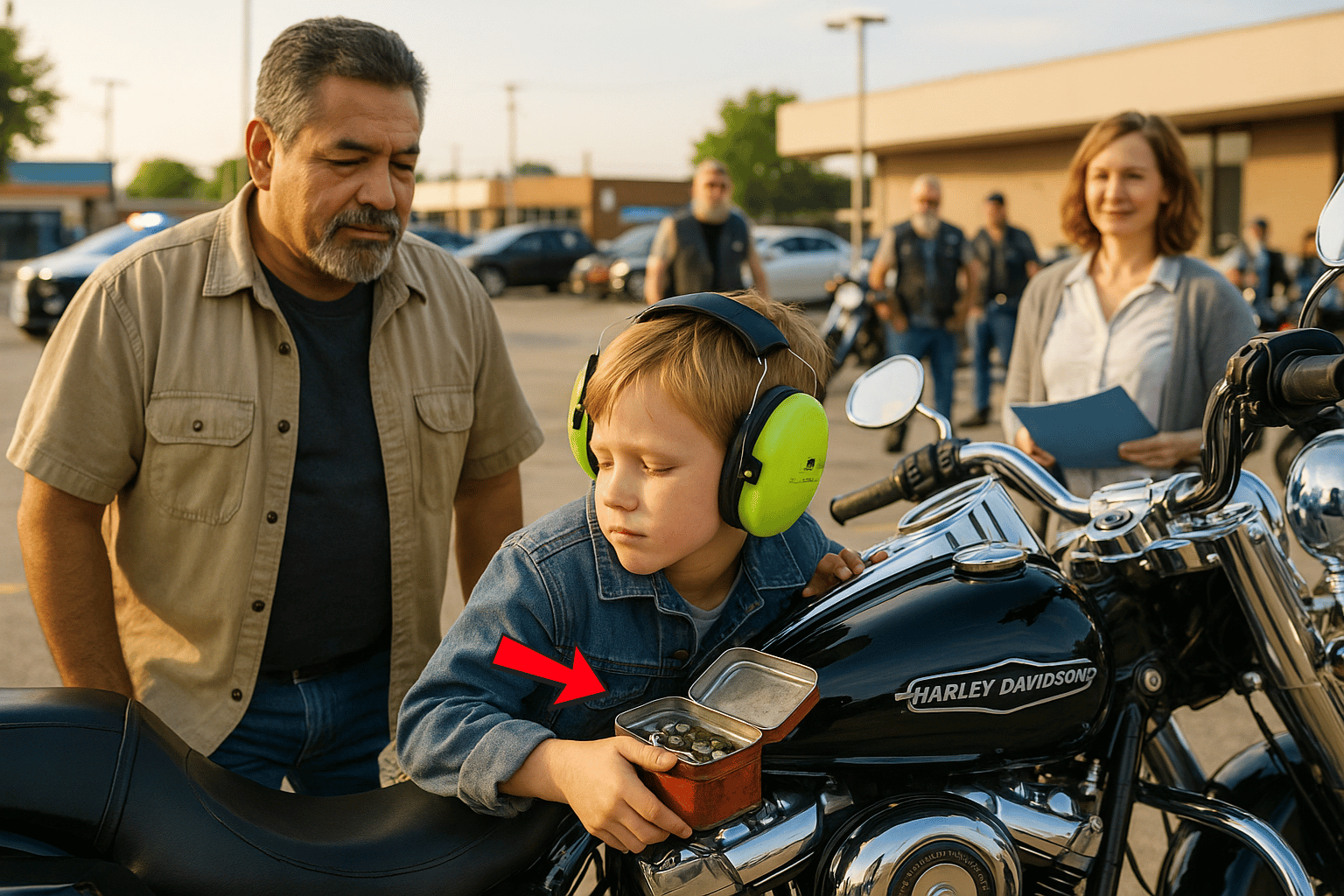

I keep child ear defenders behind the register. The Riders buy them by the case every August with the backpacks we donate to the elementary school. I eased the muffs over the kid’s head the way you offer a bird your palm. He let me. He mapped the engine guard with two fingers, then the tank again, as if tracing a safe route through a loud city.

“Name’s Ray,” I told him. “This bike’s called Heartbeat. Sounds like you figured that out.”

Blue lights slid along the far curb. Two cruisers rolled in calm and slow—the gait of people who live along the edge. One officer radioed Child Protective Services. The other crouched, eyebrows asking permission. I lifted a palm: quiet. He nodded.

“Buddy,” I asked the kid, “this the only sound that doesn’t hurt?”

His answer was more vibration than voice. “Yes.”

Later I learned it was the first word he’d said to anyone in months. In the moment I only knew the ground steadied.

He still had the lunchbox. Dented, red. He tipped it open himself when my hand got close. Inside: a tiny mint tin, now filled with bolts, washers, and nuts of different sizes. Each piece was labeled in tiny, careful handwriting with a date. He pinched one, set it on my floorboard, and tapped once. If you’ve listened to engines long enough, you recognize the message.

Order from noise. One small steady thing.

Part II — Intake

Fifteen minutes later a county sedan parked clean. Ms. Greene stepped out—CPS—folder tucked to her ribs. We knew each other. Last winter I’d loaned her a portable heater so spare blankets stayed warm in her trunk.

“Ray,” she said, then saw the boy. “Hi there. I’m—”

He tightened on the tin. Even with the muffs, her voice wobbled the air. He sidled closer to the Harley like a door he could lock by standing inside it.

Greene didn’t push. “We got a call,” she told me. “Anyone know his name?”

“You can ask,” I said, “real gentle. Like you’re talking to a deer.”

She angled her mouth into a smile. “Hi, honey. I’m Ms. Greene. What’s your name?”

He watched the sky parade in the tank’s reflection.

“It’s okay,” I said. “You can tell her later.” Then, to Greene: “Let me keep him here for a bit.”

“You know the drill.”

“Dee’s on her way,” I said. With the Riders, she’s our logistics brain; with CASA she’s a Court Appointed Special Advocate. Yellow scooter, stickers, and the family court calendar memorized.

“Emergency placement?” Greene asked, hope tucked inside the fatigue.

“If he wants it.” I looked down. “You want to wait with me, buddy? Just for tonight?”

The nod wasn’t a maybe. It rose from his heels and rolled up through his spine.

Greene exhaled. “Okay.”

When he lifted the lunchbox lid later, I saw crooked vinyl letters stuck to the paint on the inside.

NOAH.

Behind the tin was a school photo: same kid, younger; chin up, eyes somewhere else. Passport picture. Proof of personhood.

I made mac and cheese because gentle food is an important tool. Blue bowl—doesn’t clang the spoon. He ate standing at the counter by the open bay because some kids sit and some kids need exit lanes. I didn’t correct him. I don’t correct wind either.

“You can use words,” I said, the way my wife would tell me when grief cauterized my mouth. “Or you can point. Either way, I’ll follow.”

He touched his muffs, then the tin, then the Harley. He tapped twice, stopped, listened inward. “Steady,” he said.

“Steady’s the best flavor we’ve got,” I answered.

I built him a corner: weighted blanket, warm bulb lamp, a shelf for the tin. I rolled my small tool cart inside, cleaned the drawers, labeled them with a Sharpie: 1/4″, 3/8″, 1/2″. He traced the letters with a finger, reading without sound.

He took the marker, flipped the lunchbox, drew a square and circled it. Then he tapped the Harley, the square, and my chest. “Home,” he said—like the word had walked a long way to get here.

We did not interrogate the storm. We made soup and waited.

Dee arrived with forms and a buzz of scooter and useful calm. She showed Noah her CASA badge, then her helmet with goofy stickers. Asked permission to set it by his tin. He nodded.

Greene returned with a bag packed in a hurry. “We’re at capacity,” she said on the porch, voice low. “We have good foster folks—they’re tired.”

“We all are. Let him catch breath here.”

“You’ll need a walk-through and background,” she said, checking boxes in the air. “The judge will want a plan.”

“I’ll give him one,” I said. “Steady.”

She looked at the scuffed boards, at the tidy line of bolts on my rail, at the Harley waiting like a friendly animal. “Steady,” she repeated, and something in her shoulders let go.

Part III — The Lane

The Second Chance Riders showed up at sunup because that’s who we are: you call, we arrive with coffee and tool belts. If you only look with one eye you see leather and patches. Look with both and you see night-shift hands that learned gentleness the hard way.

We fixed the loose porch step. Added a handrail because kids like a thing to hold while deciding. Felt pads on chair legs. Swapped the hall light for one that warms up instead of slapping on. Bear—gentle as advertised—opened a demo carburetor and let Noah lean so close his eyelashes brushed metal. Snake, boots off, sat cross-legged on a mat and counted breathing with the idle.

“In for four, out for four,” he said in a bass that keeps rooms honest. “If the world revs, keep your lungs on idle. You decide.”

Noah selected a nickeled bolt from his tin, placed it between them like sacrament. Snake nodded like a man receiving communion.

By noon we’d hung a KNOCK SOFT sign and killed the doorbell. I kept both bay doors open because Noah needed ground-to-sky lines. He paused sometimes at the threshold just to breathe, shoulder blades lifting like small hills.

That afternoon a man stopped at the bottom stair, hat in hand—Marcus Carter, from two streets over. We’d traded hellos for years. He held the hat like wet paper.

“I heard my boy was here,” he said. He didn’t push past me.

“Greene called you?”

He nodded. Stood still.

“I’m working on myself,” he said. “Not there yet. Working.”

I believed him—not for the words, but for the stillness. People who are lying can’t keep their hands plain.

“You can sit,” I said, motioning to the chair we’d just sanded. “You can see him from there. If he wants closer, he’ll choose it.”

Marcus sat. No grand speeches. No tears. No bargains with next time. He watched his son stand in a triangle of sun and listen to a machine like it could bless him.

Noah noticed. He took two steps forward, one back, opened the tin, rolled three bolts across his palm and set them on the step, neat as a paperclip row. He tapped each—one, two, three—then tapped his chest, then the Harley, then the bolts. Not a sentence. A map.

“Hey, little man,” Marcus said, voice steady. “I see you.”

Greene came as daylight softened. She sat with us and named possibilities without promising what can’t be promised: milestones, supervised visits, support groups, a CASA coach. We wrote a plan on my porch built like a good shelf—square, simple, more studs than you think you need.

That night Noah set the smallest bolt by my coffee mug, pointed at the bike, tapped his chest, lifted his palms like a scale. “Idle,” he said.

“Idle,” I agreed. “We don’t have to rev to get home.”

He fell asleep under the weighted blanket on the couch; I took the recliner within earshot. Around two a.m., thunder rolled far off and he startled. I didn’t say it’s okay. I said, “We can count.” We did. Four in, four out, until the storm moved through both of us.

Part IV — Inspection

The walk-through smelled like cut grass. Greene clicked her pen. Noah smiled at the click. We tested smoke alarms. She checked the extinguisher. The Riders “found” chores: raked leaves that didn’t need raking, set a deadbolt that wasn’t essential. Dignity is jobs for hands.

Greene asked Noah if he felt safe. He didn’t answer with words. He poured the tin—five bolts—and arranged a porch and a circle out front. Tapped the circle. “Steady.”

“That’ll preach,” Greene said, and made a checkmark.

The court date landed like sudden rain. We wore our Sunday best—clean denim. Dee sat with Noah on a bench and let him spin her ring like a worry stone.

Inside, the judge was kind the way old oak is kind. He asked about school pickups and smoke detector chirps. He asked Noah if he wanted to speak. Noah shook no. That was fine.

Marcus stood. No performance. “I’m showing up to meetings, to work, and to quiet,” he said. “I’m not here to pull him away today. I’m here to stand where he can see me.” The judge wrote for a long breath.

Halfway through, Noah tugged Dee’s sleeve and pointed at counsel table. The bailiff conferred; the judge nodded permission. Noah poured bolts, sorted by size and shine, made a square, then a stepping-stone line to the square. Tapped each stone in time with his breath. Looked up. “Please,” he said. “Don’t… rev my life.”

No one coughed. The judge removed his glasses and polished them with the robe hem—a move that buys a man his face. He asked if I understood the responsibility. Yes. Asked Marcus if he’d work the plan we’d built on the porch. Yes.

Guardianship to me with reviews. Supported contact for Marcus. The judge didn’t call it a victory. He called it a beginning. He told Noah his granddad once rebuilt a mower and kept the extra spring as a lucky piece. “Sometimes the extra part reminds you things can still run even when not every piece goes back where it used to live.”

Outside, the Riders didn’t hold a ceremony. We lined the curb with bikes, turned keys to ON, and let sixty seconds of idle roll like surf. Noah counted under his breath, pocketed the smallest bolt, and clicked the tin shut. “Home.”

We took the long way back—steady through neighborhoods of sprinklers and porch swings. People looked up and didn’t see a wall of noise. They saw a lane.

Part V — Habits of Home

Life after court isn’t a parade. It’s a list on the fridge, sneakers by the door, a lunchbox on the counter. Tuesday spaghetti because Tuesday likes a plan. Supervised visits in a park pavilion. Greene arriving with picture books and a yawn. Marcus showing with a thermos for me and a notebook for Noah because he read that some kids draw better than they talk. Dee clapping once in the doorway when Noah holds up a bracket he bent straight in the vise.

Words came, not like a river, but like good screws—right size, set carefully. He told me thunder sounds different when it’s far. That the cafeteria smells like pennies. That the Harley’s shadow on Fifth turns us into giants with regular-sized heads. He whispered to the engine sometimes when he thought I wasn’t listening. I was always listening.

We built a ritual for rough days. I’d roll Heartbeat half out of the bay. Noah stacked three bolts on the floorboard like a cairn. We counted to four. Sometimes we didn’t even start the bike. Sometimes idle is a picture you stand in front of with your hands in your pockets.

At school, someone smart realized ear defenders weren’t a crutch; they were a key. The vice principal—weekend Softail rider—came by our backpack drive. On Friday nights a Rider looped past the soccer field so Noah could hear the hum under the cheer and know the hum would be waiting at the house.

One fall evening Marcus stood in my yard with his hat again. We watched geese stitch the sky into a V. “I’m learning there are days the kindest thing is letting someone else pull the air for a while,” he said. “Thank you for not treating me like a wrong note.”

“You’re not,” I told him. “You’re part of the song.” He laughed, lighter, and asked to learn his own oil change. We knelt and stained our hands on purpose.

Part VI — Wintering

We hung quilts over doorways the way my grandmother taught me. On the coldest night, furnace humming like a big content animal, Noah poured the tin on the coffee table and arranged the bolts into H O M E. He tucked one long screw into his pocket. “Lucky piece,” he grinned. “For loud school.”

He grew like kids grow when the ground quits shaking. Learned where every washer lives. Learned to set a torque wrench and to stop when it clicks. Waved to the bus with his whole arm. Said “you first” at doors. Learned that some storms pass and some stay, and both can be handled with a plan, a blanket, and a sound that remembers.

Part VII — The Loop

Spring shook frost off the grass. The Riders did our charity loop to the river and back—a course that feels like turning a page. We put Noah mid-pack—Snake ahead, Bear behind—so he could feel a lane made of friends. He wore a cut-down vest the ladies stitched with a patch that said HOME in thread pulled from my retired jacket. Crooked. Perfect.

At the halfway stop a gray-haired man asked for a photo for the rec center board. I looked at Noah. He studied the ground, then nodded and held up his tin like a medal. The picture flared with sun and somebody’s elbow photobombed and Snake’s knuckles showed a scrape. Better than perfect. True.

On the way back a blue wall built in the west. Big summer drops found us on the hill. We ducked under the old bridge where the graffiti is cheerful. “You okay?” I asked.

Noah slid his muffs on, set three bolts on the seat, tapped them four times. “Steady,” he said, smiling around the word.

We waited out the worst with jackets over our heads like kids on a porch. When the rain eased to what the road could hold, we rolled slow toward home.

Part VIII — Idle, Again

The porch light threw a circle on the step where the first three bolts he ever left still sit in a tidy row. I haven’t moved them. Some things stay where they did their work.

Marcus pulled up right on time for his visit. New blue notebook, three freshly sharpened pencils. He waited for the nod before stepping in. Gratitude has a sound when it idles; he knows it now.

Inside, Noah dumped the tin and built a tiny bridge between two stacks with a washer in the middle like a safe spot. “This is how you meet in the middle,” he said. “You don’t have to jump. You can walk.”

I don’t know the years ahead. No one does. But I know this: some homes grow from houses, some from habits, some from the exact pitch of a steady sound. The world is kinder when we let our engines idle next to each other for a while and listen.

On certain nights the shop is dark and the road is a ribbon with no knots. I sit on the step and hear the city breathe. Inside, ear defenders hang on a hook like a promise. Tins stack like treasure. The Harley tick-ticks as it cools, a heart easing toward rest. If a car slows out front and somebody’s having a hard day, I hope they hear it—the way a life can hold quiet without breaking, the way a steady hum carries you until your lungs remember the count.

When Noah sleeps under the weighted blanket, his fist curled around the lucky screw, he sometimes smiles and whispers out of the old habit—not to the engine anymore but to the room itself.

“Home,” he says.

Then he takes the next breath. And the next. And the next.

End.

“This story is a fictional work created for inspirational and entertainment purposes. Although it reflects real-life themes, all names, characters, and events are products of imagination. Any similarities to actual people, places, or events are purely coincidental.”