Viktor died on a gray, indifferent morning in early March.

Outside, the city was still half-frozen, as if winter itself refused to let go. The streets were quiet, the roofs heavy with melting snow. Inside, the air was still—too still.

I was sitting beside him when his breathing changed.

It came in shallow, uneven waves, like the sea pulling away from shore.

His hand was cold in mine.

“Viktor,” I whispered, my voice trembling, “I’m here.”

He didn’t answer. His eyes were closed, the lines on his face softening as if time itself had let him rest.

I pressed my forehead to his hand. “You can go,” I murmured. “You’ve done enough. I love you.”

And then he stopped breathing.

It was so quiet that for a second, I thought the world had stopped too.

Even the clock on the wall seemed to pause between ticks.

When I finally stood, my legs were trembling.

I opened the window. The cold air rushed in, carrying with it the distant sound of church bells. I wanted to believe that maybe someone, somewhere, had felt the same emptiness open inside them at that very moment.

The sons arrived before noon.

Two men in expensive coats, their faces tight, their eyes red but dry.

They didn’t hug me. They didn’t even say hello. They went straight into his room, closing the door behind them.

I stood in the hallway, clutching the hem of my sweater. I could hear their muffled voices through the door—short, clipped sentences in Czech.

When they came out, they looked exhausted, and older somehow.

“We’ll handle the arrangements,” the older one said. “You should… rest.”

As if I were just a housekeeper who’d done her job.

The funeral was small but beautiful.

A brass cross, white flowers, quiet murmurs.

Friends and colleagues came, patted the sons on the shoulders, whispered condolences. Hardly anyone looked at me. I was the foreigner, the outsider, the woman who had come into his life too late and, in their eyes, for the wrong reasons.

Katya flew in from Prague for a day. She hugged me so tightly I could barely breathe.

“You did everything you could, Inna,” she whispered. “He loved you.”

But even her words couldn’t fill the hollow that had opened in my chest.

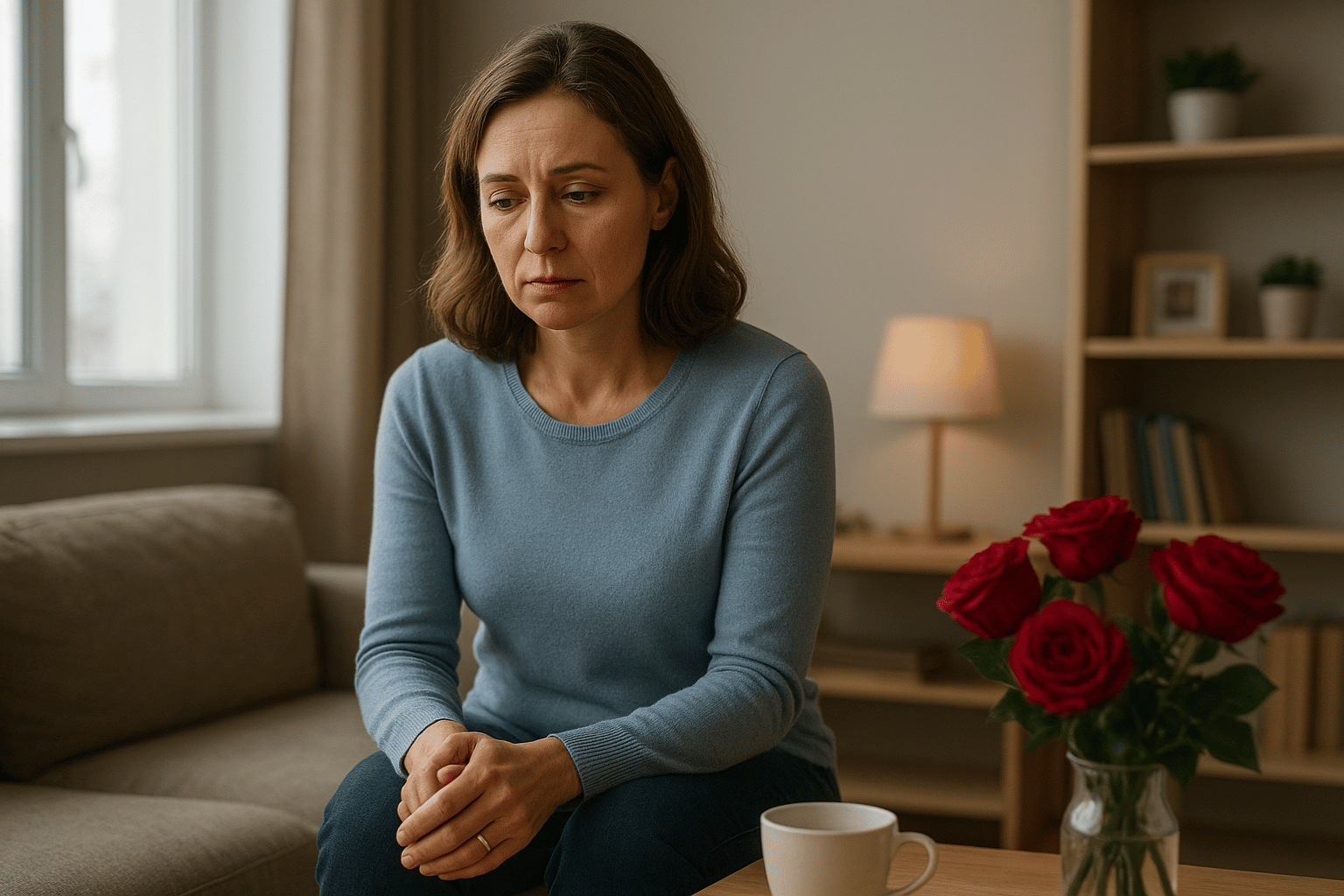

That night, when everyone left, I came back to our house alone.

The silence felt heavy. His slippers were still by the bed. His cologne lingered on the pillow.

I sat in the kitchen, drinking tea gone cold, staring at the chair where he used to sit.

For the first time in years, I felt truly, terrifyingly alone.

Two days later, the doorbell rang.

When I opened the door, both sons were standing there. No flowers, no condolences. Only seriousness.

“There’s something we need to discuss,” said the elder.

I stepped aside, letting them in. The air between us was thick.

He took out a folder—papers, stamps, signatures.

“Our father… changed his will,” he said, watching me closely. “He left you the house.”

The words hit like a slap.

“That can’t be,” I whispered. “He said everything would go to you.”

The younger one’s jaw tightened. “It’s your doing. You got to him when he was weak.”

My throat went dry.

“Do you really think I cared about the house?” I asked quietly. “I cared about him. About keeping him alive as long as I could.”

They exchanged a look—a silent agreement that I was lying.

The elder one exhaled slowly. “We’ll be contesting it. You’ll hear from our lawyer soon.”

And then they left. Just like that.

The following weeks blurred into a fog of letters, hearings, and sleepless nights.

Every envelope that arrived made my hands shake. Every phone call began with a cold, official voice.

At one point, their lawyer—a man with kind eyes but a sharp tongue—asked, “Mrs. Kovářová, are you sure you didn’t pressure him into signing?”

I stared at him for a moment, then said, “Have you ever watched someone you love die? There’s no pressure left in you after that. Only grief.”

He didn’t ask anything else.

When the court finally made its decision, I wasn’t even in the room. My lawyer called.

“It’s over,” he said. “The will stands. The house is yours.”

I hung up, staring at the phone in silence.

Victory felt meaningless.

The house wasn’t a prize—it was a mausoleum. Every step echoed with memories: his laughter, his cough, his voice calling my name.

Still, I stayed. I couldn’t leave. I planted roses in the garden—deep red, like the ones he’d brought me at the airport the day he proposed.

Katya called every week.

“You should move back,” she’d say. “Start over, find someone new. You’re only forty-five, Inna.”

“Maybe,” I’d answer. “Just not yet.”

Because every morning, when I opened the curtains and the sunlight fell across the table, I could almost see him there—reading his newspaper, his glasses sliding down his nose, that little smile playing at the corner of his lips.

Sometimes I talked to him out loud.

“You were right, you know,” I’d say. “I never wanted your property.”

And in the quiet of the room, I’d almost hear his voice again—gentle, amused:

“I know, my Inna. I always knew.”

Epilogue

Years later, when the roses in the garden bloomed thick and full, a neighbor passing by said, “Your husband must have loved these flowers.”

“Yes,” I replied softly. “He still does.”

And as the wind moved through the petals, I felt, for the first time in a long while, that I wasn’t alone at all.