The auditorium smelled of polished wood and freshly printed papers. I had spent years preparing for this moment, yet when the final applause faded, it wasn’t my achievement that caught the room’s attention, it was the man quietly sitting in the back row, leaning forward slightly, watching every word I spoke. That man was Henry Walker, my stepfather, the one who had built the foundation beneath my life long before I even knew what a PhD entailed. I had never known a perfect childhood. My mother, Emily, separated from my biological father when I was very young. I barely remembered his face, only the emptiness of unanswered questions and silent rooms. Life in the small town of Riverfield, surrounded by rice paddies and dusty roads, was quiet and unforgiving. Comfort was scarce, and even love was measured in the time it took to return from work or the food left on the table.

When I was four, my mother remarried. Henry arrived not with wealth or influence, but with a worn tool belt, hands hardened by cement, and a back straightened by years of labor. At first, I resented him. His hands smelled of dust and mortar, his boots always covered in grime, and his stories were of projects I could not yet understand. But slowly, I learned the language of his love. He mended my broken bicycle, stitched the torn soles of my sandals, and rode his creaky old bike to pick me up when bullies cornered me at school. On those rides, he never lectured, never scolded. He spoke once, softly, yet it imprinted itself on my heart:

— “You don’t have to call me father, but know that I will always be here when you need someone.”

From that day, “Dad” became a word I used without hesitation.

My childhood with Henry was simple but vivid. I remember the evenings when he returned home with a dust-covered uniform and tired eyes, asking only one thing:

— “How was school today?”

He could not explain calculus or literary theory, yet he insisted I study diligently, always saying:

— “Knowledge is something no one can take from you. It will open doors where money cannot.”

Our family had little, yet his quiet determination gave me courage. When I passed the entrance exam to Metro City University, my mother wept with joy, but Henry merely sat on the porch, puffing a cheap cigarette. The next morning, he sold his only motorbike, combined it with my mother’s savings, and arranged for my journey to the city. His clothes were worn, his hands rough, yet he carried a small box of gifts from home—rice, salted fish, roasted peanuts—and left me with a final word of encouragement:

— “Work hard, son. Make every lesson count.”

Inside the lunchbox, wrapped in banana leaves, I found a folded note:

— “I may not know your books, but I know you. Whatever you choose to learn, I will support you.”

Through undergraduate years and into graduate school, Henry never faltered. He continued laboring, climbing scaffolds, hauling bricks, his back bending further with each passing year. Whenever I returned home, I found him at the edge of a construction site, wiping sweat from his forehead, still watching over the work as if he carried my education on his own shoulders.

I never dared tell him how much he inspired me. The PhD path was grueling, but he had taught me perseverance long before I understood it.

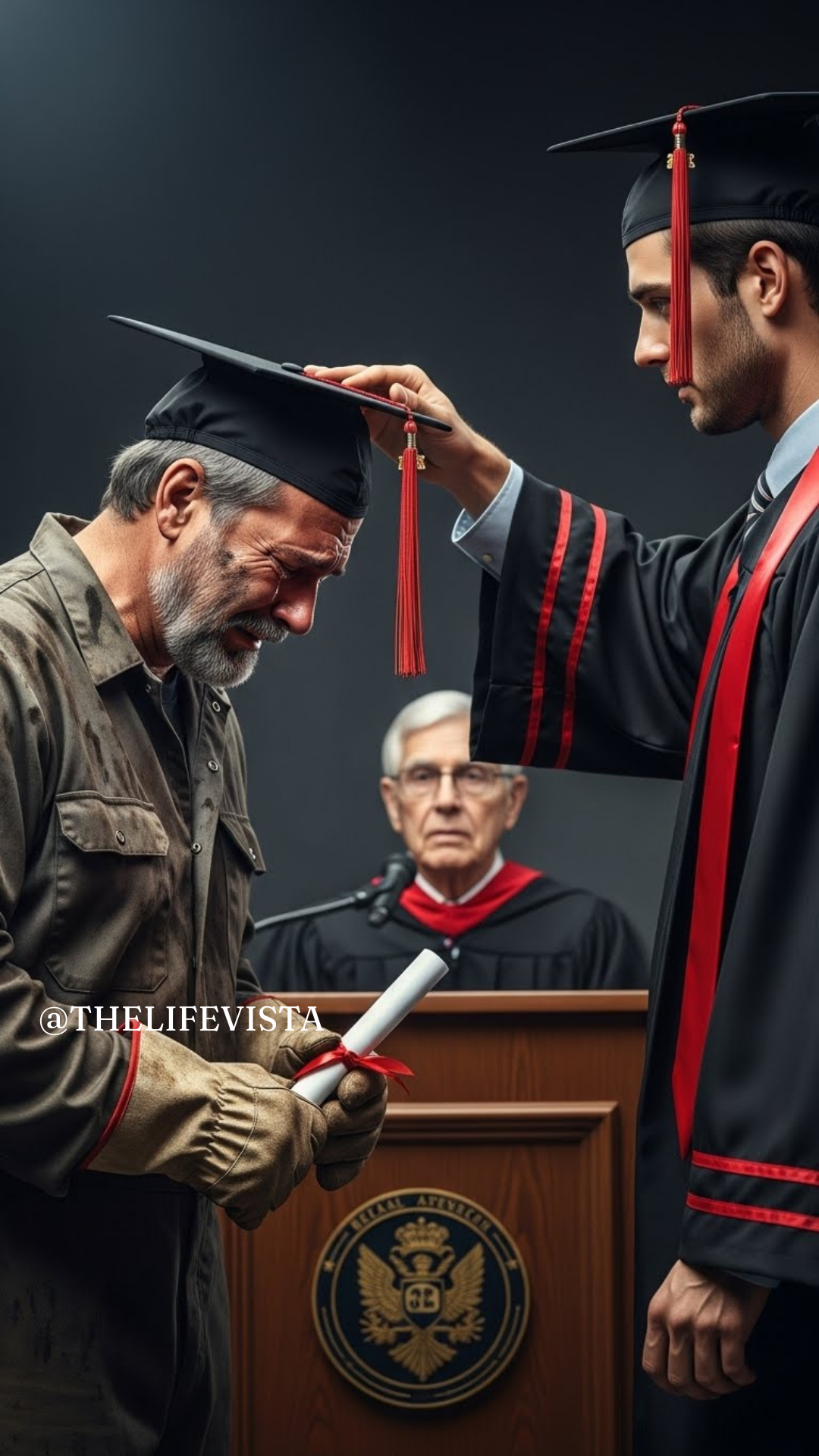

On the morning of my defense at New Vista University, I pleaded with him to attend. Reluctantly, he borrowed a suit, polished shoes a size too small, and wore a new cap from the local market. He took a seat at the back of the hall, straightening as much as his aching back allowed, eyes fixed on me.

After the presentation, Professor Adrian Miles approached, shaking hands with each of us. When he reached Henry, he paused, squinting as if recognition had struck. Then a slow, warm smile spread across his face:

— “You are Henry Walker, aren’t you? I grew up near a construction site in Maplewood District. I remember a worker who carried a colleague down scaffolding, even while injured himself. That was you, wasn’t it?”

Henry barely moved, silent in his humility. Professor Miles continued, voice thick with emotion:

— “I never imagined I would see you again, and now you are here as the father of a new PhD graduate. Truly, it is an honor.”

I turned back to see Henry smiling, eyes glistening. For the first time in my life, I understood: he had never sought recognition, never demanded repayment. The seeds he had planted through years of quiet devotion and tireless work had finally borne fruit, not for him, but through him.

Today, I am a university lecturer in Metro City, married, with a small family. Henry has retired from construction, tending to his vegetable garden, raising chickens, reading the morning paper, and riding his bicycle around the neighborhood. Occasionally, he calls to show me his latest tomato bed or to offer eggs for my children, joking with his familiar humor.

— “Do you regret all the years of work for your son?” I once asked.

He laughed, deep and content:

— “No regrets. I built my life, yes, but the thing I am proudest of is building you.”

I watch his hands as he moves them across the screen in a video call—the same hands that carried bricks, cement, and burdens for decades. Those hands built not a house, but a person.

I am a PhD. Henry Walker is a construction worker. He did not merely construct walls or scaffolds, he built a life, one lesson, one act of quiet love at a time.