Her boss mocks her and asks her to dance… not knowing she’s facing a former professional ballerina Avery Collins had perfected the art of being overlooked.

She moved through the 62nd floor of Sterling Enterprises like someone whose edges had been smoothed by countless small compromises: the charcoal pencil skirt that hugged her hips without invitation, the crisp white blouse that read as professional and anonymous, the low bun that kept hair out of both her face and other people’s line of sight. Her hands were efficient, economical—file folders arranged in exacting rows, calendar alerts set with the quiet precision of a metronome. Coffee at 7:45 a.m. Three sugars, no cream. Contracts flagged with color-coded tabs. Every gesture was measured, nothing wasted, nothing loud.

At twenty-nine she had been Lucas Bennett’s executive assistant for three years. He was the kind of CEO who occupied every conversation he entered: tall, broad-shouldered, with hair just starting to silver at the temples and a presence that bent a room’s attention toward him without his needing to speak. Lucas didn’t demand affection; he took it by default. In the office his interactions with Avery were short and practical, a mode of communication that suited them both. She was competent—exactly what he needed. Invisible, she told herself, was safe.

Underneath that careful safety, muscle memory hummed: a line of the arm, an effortless turnout, the way to breathe through a complicated sequence so that performance became illusion and not strain. Those movements were old habits, leftover from a life she had scrupulously abandoned—the life that had once given her a name people whispered at Lincoln Center: Avery Lawson, principal dancer, a supposed once-in-a-generation talent. The corporate rhythm had been an elegant camouflage.

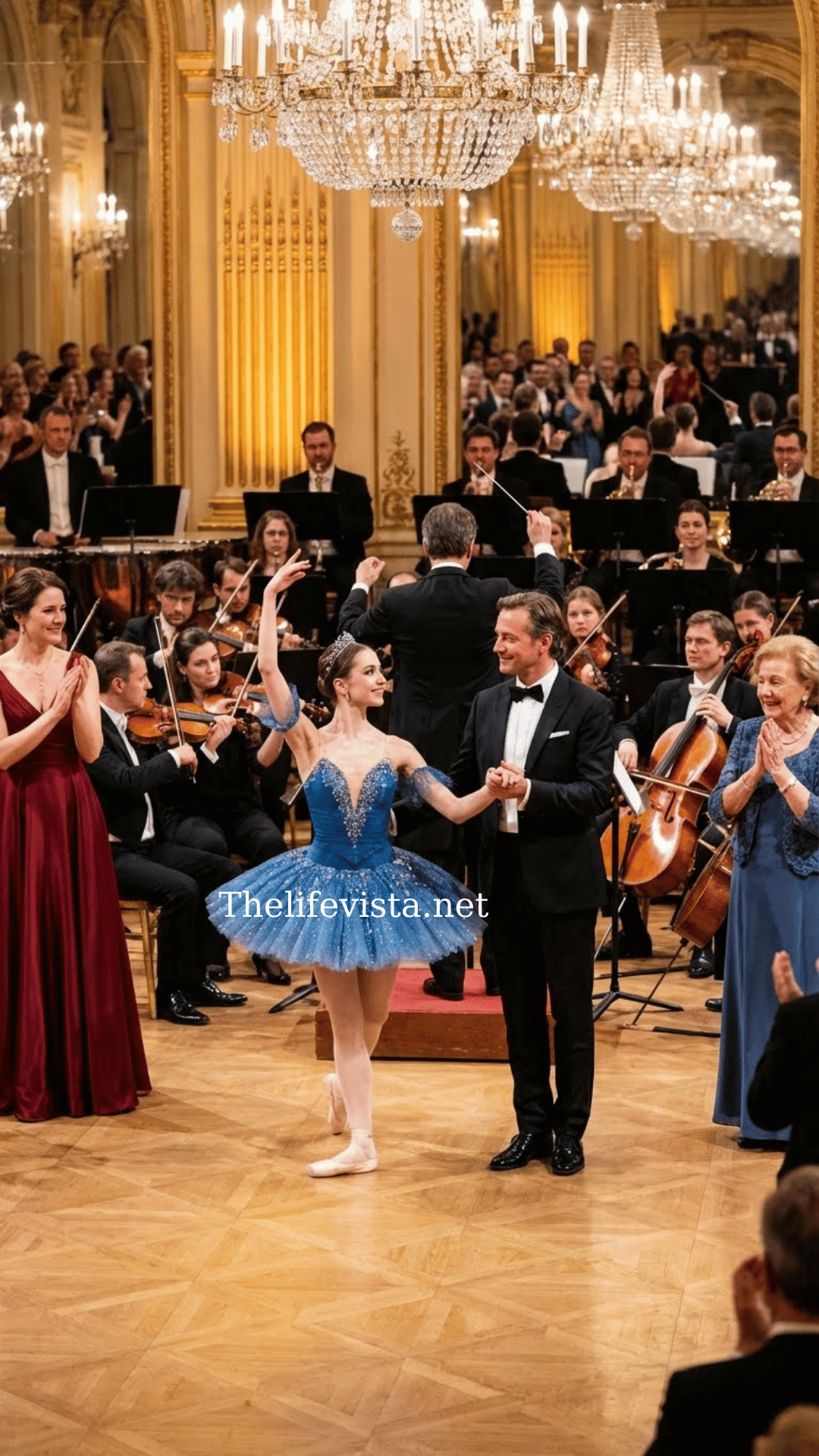

The Bennett Foundation Gala arrived like a sudden tide. It was the social event of the season—crystal chandeliers, glittering gowns, donors with pedigrees and checkbooks. Lucas’s mother, Margaret Bennett, chaired the event and expected precision. Avery managed logistics with a kind of quiet heroism. She booked travel for a last-minute patron, negotiated a timing conflict with the orchestra, and smoothed the small catastrophes that masquerade as inevitable on nights like this. Each success was a quiet reward: a nod, a barely audible “well done,” the relief of another problem solved.

She had said from the beginning she would attend as Lucas’s plus-one, and her acceptance was nominally a professional duty. In private, she felt the old electric dread that came with visibility. Photographs. People asking who she was. Cameras that turned anonymity into headlines.

On the night itself she wore the midnight-blue gown Lucas’s personal shopper had chosen—classic, restrained, a fabric that caught light like still water. Lucas moved through the room with his mother, and she stayed a step behind, whispering names, offering facts. People glanced sometimes, curiosity pricked by the sight of a woman they had never met beside one of Manhattan’s most visible men. She melted back into the background the way a dancer folds into a corps. She liked it that way.

Dinner unfurled in three smooth courses, but it is the unexpected that writes itself into memory. Midway through Margaret’s speech, a flurry went through the room: the principal of the ballet company hired to perform had injured her ankle during warm-up. Panic rippled through the committee. “We promised our donors something special,” Margaret said, and her voice carried the kind of authority that makes people move.

Daniella Pierce, Sterling’s marketing director, seized the moment with the predatory eagerness of someone who smelled leverage. Her smile was sharp as a headline. “What a shame,” she said from the neighboring table. “Perhaps some guests could participate. Make it interactive.”

The comment was a barb aimed at Avery—an invitation to humiliation disguised as entertainment. Daniella had always been territorial with Lucas. Her presence had the gloss of ambition and the underside of envy. She was counting cards: a public moment, a chance to unbalance an employee who had somehow become more than that.

Lucas’s eyes lifted. “Miss Collins is far more than an assistant,” he said, and the small shift in tone made Avery’s breath catch. “But I confess—” he turned to her with a playful look that warmed something in her chest, “—I don’t actually know if dance is among her talents.”

All eyes drifted to her table. Margaret held her gaze with that maternal curiosity that can be as probing as interrogation. “You carry yourself with wonderful posture,” the older woman said. “Have you had any dance training?”

Avery felt the cold press of the room’s attention. She had rehearsed retreat a thousand times in small ways; this was larger. Daniella’s smile was a wolfish thing. “Perhaps you could give us a small demonstration,” she said sweetly. “Just a few positions—ballet is charming, after all.”

It should have been easy to say no. Hide, shrink, be safe. Instead something else stirred—a muscle memory of courage and stubbornness trained into her in studios and one-night aisles of applause. Avery had built a life around running from the epicenter of her pain, but perhaps running had simply been avoidance, not healing.

“Some,” she said. The word left her small, brittle. “A long time ago.”

Daniella clapped softly—victory. “Oh, come now. Just a few steps.”

Avery stood. The cool marble floor beneath her bare feet steadied her in a way that no polished shoe ever could. She had taken off her heels. That nakedness felt less vulnerable and more honest. A small clearing had opened in front of the stage; the orchestra waited, brow knitted. She named a piece—Tchaikovsky—and the conductor’s eyes widened in recognition. When the first notes filled the room, something inside Avery rose like a memory.

She didn’t offer merely a demonstration. She wasn’t a party trick. For three minutes she resurrected an entire life. The body remembered what the mind had tried to bury: endless hours of pliés, arabesques sent out like invitations to the air, petit allegro turned into a flurry of crisp footwork, a controlled adagio that stopped the room like a held breath. Her movements were technically exact, but what made people stand was a thing harsher to teach: the sincerity of emotion. Where she had once moved to earn applause, she now moved to tell a story—of fracture and repair—through muscle and line. When she ended in reverence, the ballroom’s silence lasted only long enough for an entire generation of indifference to be swept away. Then applause cascaded like rain.

Lucas watched with a look she didn’t understand—equal parts recognition, wonder, and something nearer to awe. He stepped forward, hand extended, and when Margaret took both her hands and called, “My God, child—who are you, really?” the dam that had kept Avery’s history separate from her present broke.

She let the truth out like a small surrender. “I used to be someone else,” she said. “Avery Lawson.”

The name landed like a stone. For the first time in years the person who’d been Avery Lawson rested unmasked in a room full of people who had known her by reputation, and people who hadn’t known her at all. Daniella’s schadenfreude curdled into white-faced shock. Videos of her performance lit up phones and feeds—“Mystery woman stuns at charity gala”—and in one night, her careful invisibility dissolved.

The next morning at Sterling she arrived early. The building was quiet, the city still waking. Her phone had not stopped buzzing. Messages from dance colleagues, old mentors, even some fans. She pressed her temple with one hand and tried to breathe.

Lucas was already in his office when she slipped in. He stood at the window, hands in pockets, the city laid out behind him like a map. He turned when she closed the door, and for a long moment they simply looked at each other.

“Mr. Bennett,” she began, then corrected herself—“Lucas”—and the formal syllables fell away. “I apologize if my—last night—caused any embarrassment to you or the foundation. If you feel my continued employment is inappropriate, I understand.”

He put on his chair and waved her toward the seat across from his desk. “Sit,” he said. The command was gentle, not CEO steel. “I spent the weekend reading about you.”

She waited for the inevitable—some corporate rebuke for unpredictability. Instead he said, “Avery Lawson: principal dancer, American Ballet Theater, youngest to be promoted to principal in company history. Critics called you extraordinary. You were about to debut as Odette, and then you disappeared.”

The long-suppressed memory rose: the lift gone wrong, the moment in rehearsal when a partner’s timing failed and the world pivoted under her feet. The crack as her ankle collapsed like wet glass. The operating room lights, the surgeon’s measured optimism, the diagnosis rendered with the kind of bluntness that becomes a sentence: you will walk, but not dance professionally.

“I walked away,” she said. The statement was flat, the kind of thing used to close a door. “I changed my name, moved, and learned how to be someone ordinary.”

Lucas moved from behind his desk and sat in the chair beside her as if proximity could change the narrative. “You were never ordinary,” he said. “You were hiding.”

There was a difference, she conceded. Hiding had not always been protective; often it had been an indictment. He told her, softly, that the gala had raised two hundred thousand dollars more because of her performance. Calls were pouring in; arts organizations wanted her. Margaret had already spoken to several potential partners. And then—unexpectedly—he offered her something she had not dared ask for.

“I want you to lead the dance component of the foundation’s new initiative,” he said. “Not as my assistant, but as program director. You’ll design curriculum. Recruit instructors. Work with students directly. Teach. Dance, if you want. On your own terms.”

It was a thing fragile as glass and as luminous. For six out of the ten years of her life she had been cocooned in the theatres, not in corporate children’s rooms. The idea of returning to dance made the hollow pool of longing inside her contract and expand and quiver.

“I don’t know if I can,” she whispered. “What if I’m not enough anymore?”

“Then you’ll teach them how to get back up,” he said. His voice contained an echo of his own life: a man who had built hotels and rescued failing properties by reallocating courage into architecture. “If you falter, you’ll have the people here to catch you.”

She took the job.

The months that followed were a montage: Avery visiting inner-city schools, drafting curriculums for compromised budgets and untested teachers, speaking with former colleagues who had become mentors again—Karen Miles, a grizzled former rehearsal director who still smelled like rosin and willpower; Adrian Cole, a patient physiotherapist who worked with injured dancers and taught her that recovery could be a long and precise architecture. She rebuilt muscles and routines. The foundation pilot launched in five schools and reached two hundred students in neighborhoods that had never had consistent arts instruction. Avery recruited teachers who were part idealist, part pragmatist: former professionals who knew the sting of a career curtailed and the fierce joy that comes from passing a torch.

Not everyone supported her. Daniella watched with an envenomed interest. Her comments started as offhand doubts at meetings and grew into more strategic undermining. At a board meeting she asked loudly, “How do we know Miss Lawson won’t simply disappear again when things get difficult? These kids need consistency, not someone who runs at the first sign of hardship.”

The room shifted. Conversations tightened like threaded wire. Shame surfaced—the old, private shame that had stalked Avery for six years. But Lucas did not only defend her; he cut Daniella’s suggestion down with a single declarative sentence. “Miss Pierce’s concerns are noted and dismissed. Miss Lawson has proven her resilience by building a new career from the rubble of the old. She understands loss in a way that uniquely qualifies her to help these children.”

Margaret’s nod sealed it. Daniella left the meeting furious and calculated. She would not be upstaged without a fight.

The next part of the story was less dramatic and more human: classes every Tuesday and Thursday in a Brooklyn studio that smelled like chalk and sweat, student dancers with knobby knees and fierce eyes. Avery taught discipline—plies, tendus, the small, meticulous work that scaffolds daring. But she also taught something more important: that art is both protest and prayer; that a misstep is not the end. She watched kids who couldn’t afford lessons find pleasure in moving. She watched one boy who had been expelled twice for fighting stand in first position and stay there, breath controlled, face glowing. That was the kind of small victory that held more weight than any gala applause.

Her relationship with Lucas grew in private until being private became less necessary. They shared dinners in small restaurants where neither had to be anything else: no titles, no board members. He told her, once, about the brittle hush that followed his divorce—the way the house suddenly had too many rooms, the way his ex-wife’s absence was a vacuum that swallowed weekends. “You taught me to look out of the rooms and see the rest of the city,” he said. “You made me want to build something that wasn’t just an asset.”

She told him about the raw panic the first time she left the Emergency Room after the surgery, about the nights when she had crawled into bed and wept for the shape of what she’d lost. “I thought if I vanished, I could disappear without making anyone sad,” she admitted. “It was cowardly.”

“You are not cowardly,” he insisted. “You are brave. You learned to survive.”

The winter and then spring stitched days to months. The program expanded. The kids performed at community recitals, then at a small theater, and then at a fundraiser where donors who had initially been skeptical watched with teary surprise as young bodies told stories about city life, labor, and love. Lucas was proud—publicly and quietly. Daniella’s influence waned. In her anger she accepted a position in Los Angeles, framed as a fresh start, and the office breathed easier.

There were private battles too. Avery had nights where her ankle ached as if the injury were a living thing, clinging. She had flashbacks in rehearsal rooms—white lights too bright, a partner’s breath too close—and sometimes a panic would rise that made her legs carbon-weak. She learned to manage those nights rather than be defined by them. Adrian, the physiotherapist, would leave her a dry towel and a look that said less, but the best truth: “The body’s history doesn’t have to be its fate.”

When the foundation’s spring gala arrived, it felt like an exam. She had promised a full piece—something she choreographed to Debussy. The risk was physical and emotional: to dance not for charity spectacle, but to show children new possibilities. The auditorium thrummed with people who loved Lucas and others who loved the arts and some who loved the novelty. In the front row sat Margaret, beaming, and a scattering of Avery’s old colleagues, each with the delicate, proprietary pride of those who had once nurtured a flower into bloom.

Backstage she paced. The costume was white and unfussy; the music began and bridged her past to her present. She stepped into the light and, in the privacy of those knowing bodies and supportive hands, she found surrender. For the first time since the injury the choreography was not a performance she measured against a phantom of perfection; it was an offering. The piece held a moment where she balanced on that ankle, longer than comfort allowed. The silence after the last note was the kind that will test you: one heartbeat; two. Then the room erupted in a standing ovation.

Lucas was on the stage before she could step away, sweeping her into an embrace that made the applause recede until the world contained only warmth and breath. “You were magnificent,” he murmured.

She clung to him. He had been there for every rehearsal, not as a critic but as an ally. He had sent roses after a bad day and coffee the morning she doubted. He had stood before a board and risked his reputation to defend her. That night he would risk something else.

He turned to the microphone. “Thank you, everyone, for supporting the Bennett Foundation,” he said, his voice steady. “Tonight you saw the power of art. You heard the testimony of children who will carry this program forward. But I have a personal announcement as well.”

The lights narrowed; dozens of lenses swung like curious insects. He dropped to one knee.

“Avery,” he said. “You walked back into my life when I didn’t even know I was waiting. You taught me what it means to be brave. Will you marry me?”

For a second the arch of the moment seemed too grand for any private feeling. The room inhaled with her. She looked at him—this man who had seen the worst of her doubts and accepted them, who had held her after a fall and believed, with a quiet ferocity, that she could dance again and that she deserved to love. She thought about being asked this question on a stage full of eight hundred people and about how she had spent years hiding a name and a body and now being asked to answer, in front of everyone, whether she would stop hiding forever.

“Yes,” she said. The single word fell out and settled like a stone in a deep pool. It wasn’t the dramatic “yes” of a press release. It was the real one: Yes, keep building with me. Yes, I will step into the difficult things with you at my side. Yes, let’s make a life that contains both fracture and repair.

They married in September, in a small ceremony by a river that caught the sky. Margaret cried in a way that left splotches on her cheek and laughed afterward when Lucas tried to feed cake to Avery and missed. Karen flew in, bringing a bouquet that smelled like the inside of a rehearsal room, and Adrian gave a toast about the stubbornness of bodies. Daniella sent a card—an attempt at civility—and Avery folded it into the memory of learning how to let people go.

The foundation’s dance initiative became more than an episodic lesson plan. Avery established scholarships for kids who needed uniforms and pairings with physical therapists who could tend to their bodies when the city tugged too hard. When the small company idea took shape—“Second Chance”—it was both practical and radical: a troupe that would give dancers a platform when injury would have otherwise sent them away. The company’s first season was a modest success, but the more important detail was the rippling effect: students in neighborhoods once deemed artless now had classes, had mentors, had a stage to rehearse on that didn’t require a velvet rope.

On a rainy Tuesday two years after the gala, a coach at a neighborhood school hugged Avery and whispered, “You saved him. He’d been quiet, and now he speaks in movement.” The line itself was a kind of proof, a gentle census of impact. She could count the nights she had wanted to hide and compare them to the nights she danced and found the balance shifted in favor of light.

Her marriage with Lucas wasn’t a perfect domestic picture; there were challenges—navigating the power dynamics of company and foundation, the glare of public interest, the small jealousies that creep in when two lives become a single project. But they worked at it with the same rigour she taught in class: honesty as training, patience as conditioning. Lucas learned to take the role of supporter without trying to fix things he had no tools for, and Avery learned—to an extent she had once thought impossible—to accept help without viewing it as charity.

There were moments when the injury still whispered: a twist on a cold morning, a misstep in rehearsal that would make the room go white. Those moments passed faster each year. The story she told herself changed; grief did not leave, but it softened into a seam of identity rather than the whole garment.

Years later, at the opening of the Second Chance’s third season, a child from the earliest cohort performed a solo that had Avery’s breath caught. He moved with the kind of fearless abandon that comes from knowing someone once believed in you enough to teach you how to get up. Afterward, a woman who had been a donor approached Avery and said, “You gave me back a childhood I didn’t know I had.”

Avery thought about the arc of her life, the way the stage had been both a place of possibility and of ruin. But she knew now that identity is not a single line. It is a braided cord of choices and fractures and stitches. She had hidden, yes; she had fled. But more importantly she had returned—to classrooms, to studios, to her body, to love—and in returning had found a life that allowed both small, private excellence and loud public consequence.

One night, many years into her work with the foundation, she stood in a studio after adults had left, lights down to a glow, and watched one of her students stay behind to practice. The boy’s ankle bled a little from a scrape, but he kept turning because he believed—or had been taught to believe—that turning was its own kind of answer. Avery walked over and put a hand at the small of his back to steady him, guiding his alignment. It was a teacher’s touch, clean and exact.

“You’re steady now,” she told him. “Keep your breath.”

He looked up, eyes bright. “Miss Avery?”

“Keep going,” she said.

She found, in that light, that she could stand with tenderness and with steel. She had learned to be seen without surrendering her softness. The woman who had once been invisible had become a person who could deliberate her visibility into action. When she walked home that night, the city hummed its litany of lights. Lucas called and asked her what she wanted for dinner; she said nothing specific and then named a street, because the answer was small and it was enough.

The path from the broken ankle to marriage to the Second Chance company was not a neat narrative. It had detours and dead ends. It had nights she wanted to crawl into a hole and not be asked where she was. But it also had the fullness of teaching, of seeing kids bloom, of being seen by someone who loved and defended her. That, she learned, was the form of courage she could live with: the willingness to be known and to keep working when being known made things harder.

At the end of the day, in the quiet of their apartment—a place that was more house with mismatched cups than a trophy of success—she would sometimes stand at the window with Lucas and watch the city roll by. “Do you ever regret stepping back into the light?” he asked once, because some questions had to be asked aloud to be answered.

She looked at him, the man who had been both a catalyst and a patient friend. “No,” she said. “I regret hiding for so long, but not the way I hid. It taught me how much I wanted to come back.”

He drew her close, hands at her waist. “Then we’ll keep building,” he said.

They did. They kept building schools and a small company and a life that made space for both the art and the human cost of it. Avery continued to teach, to choreograph, to build programs. She never forgot the feel of marble under bare feet at the gala that changed everything. She never stopped believing in the small miracle of movement.

Once, when she accepted an award for arts education, she thought of Daniella—of envy turned into a different kind of lesson—and decided not to feel bitterness. Instead she dedicated her speech to “everyone who thought they couldn’t” and to the people who helped them believe the opposite.

When she finished, the room rose and cheered, but she watched one of her students in the crowd and saw something like recognition pass between them. That was enough. The applause was beautiful, but it was not the point. The point was the work between the gestures: the hours in noisy studios, the scraped knees, the calls home, the tiny moments of confidence sewn into a choreography of a life.

In the end, it was simple. She had been mocked at a gala with a barb meant to shame. She had answered not with anger but with something sharper—a reclamation. The mocking did not shatter her; it peeled back one more layer of the person she had been hiding from the world, and from herself. And standing in the light after that, in the company of young dancers and a partner who believed in second chances, she knew that she was exactly where she wanted to be: walking forward, hands not empty but full, dancing not for an audience but for the lives she could touch.