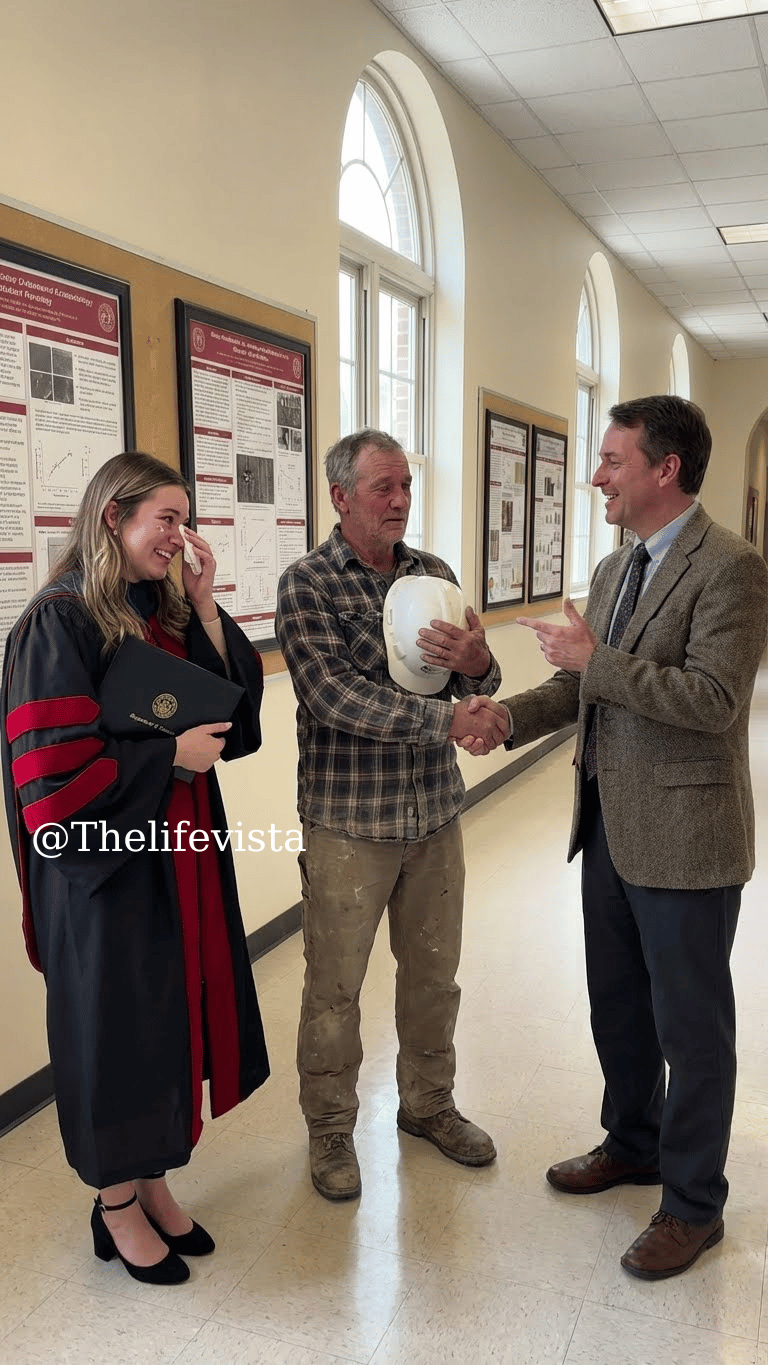

My stepfather was a construction worker for 25 years and raised me to get my PhD. Then the teacher was stunned to see him at the graduation ceremony.

That Night, After the Defense, Professor Coleman Came to Shake My Hand and Greet My Family. When It Was Mike’s Turn, He Suddenly Stopped, Looked Closely at Him, and His Expression Changed.

I was born into an incomplete family. As soon as I learned to walk, my parents separated. My mother, Karen, took me back to Nueva Ecija, a poor rural area filled with rice fields, sun, wind, and gossip. I cannot clearly remember the face of my biological father, but I know that my early years lacked many things—both material and emotional.

When I was four years old, my mother remarried. The man was a construction worker. He came into my mother’s life with nothing: no house, no money—only a thin back, sunburnt skin, and hands hardened by cement.

At first, I didn’t like him: he left early, came home late, and his body always smelled of sweat and construction dust. But he was the first to fix my old bicycle, to quietly mend my broken sandals. When I made a mess, he didn’t scold me—he simply cleaned it up. When I was bullied at school, he didn’t yell at me like my mother did; instead, he quietly rode his old bicycle to pick me up. On the way home, he only said one sentence:

— “I won’t force you to call me father, but know that Tatay will always be behind you if you need him.”

I was silent. But from that day on, I called him Tatay.

Throughout my childhood, my memories of Mike were a rusty bicycle, a dusty construction uniform, and nights when he came home late with dark circles under his eyes and hands still covered in lime and mortar. No matter how tired he was, he never forgot to ask:

— “How was school today?”

He wasn’t highly educated, couldn’t explain difficult equations or complex passages, but he always emphasized:

— “You may not be the best in class, but you must study well. Wherever you go, people will look at your knowledge and respect you for it.”

My mother was a farmer, my father a construction worker. The family survived on little income. I was a good student, but I understood our situation and didn’t dare dream too big. When I passed the entrance exam to a university in Manila, my mother cried; Mike just sat on the veranda, puffing on a cheap cigarette. The next day, he sold his only motorbike and, along with my grandmother’s savings, managed to send me to school.

The day he brought me to the city, Mike wore an old baseball cap, a wrinkled shirt, his back soaked in sweat, yet still carried a box of “hometown gifts”: a few kilos of rice, a jar of dried fish, and several sacks of roasted peanuts. Before leaving the dormitory, he looked at me and said:

— “Do your best, child. Study well.”

I didn’t cry. But when I opened the packed lunch my mother had wrapped in banana leaves, beneath it I found a small piece of paper folded in four, with these words written on it:

— “Tatay doesn’t understand what you’re studying, but whatever you study, Tatay will work for it. Don’t worry.”

I studied four years in college and then went on to graduate school. Mike kept working. His hands grew rougher, his back more bent. When I returned home, I saw him sitting at the base of a scaffold, panting after hauling loads all day, and my heart broke. I told him to rest, but he waved his hand:

— “Tatay can still manage. When I feel tired, I think: I’m raising a PhD—and I feel proud.”

I smiled, not daring to tell him that pursuing a PhD meant even more work, even greater effort. But he was the reason I never gave up.

On the day of my PhD thesis defense at UP Diliman, I begged Mike for a long time before he agreed to attend. He borrowed a suit from his cousin, wore shoes one size too small, and bought a new hat from the district market. He sat in the back row of the auditorium, trying to sit upright, his eyes never leaving me.

After the defense, Professor Coleman came to shake my hand and greet my family. When he reached Mike, he suddenly stopped, looked at him closely, and smiled:

— “You’re Mike, aren’t you? When I was a child, my house was near the construction site where you worked in Quezon City. I remember one time you carried an injured man down from the scaffold, even though you yourself were hurt.”

Before Mike could say a word, the teacher was already…. moved:

— “I didn’t expect to see you here today, as the father of a new PhD. It’s truly an honor.”

I turned around: Mike smiled—a gentle smile but his eyes were red. At that moment, I understood: in his entire life, he had never asked me to repay him. Today, he was recognized—not because of me, but because of what he had silently planted for 25 years.

Now, I am a university lecturer in Manila, with a small family. Mike no longer builds: he grows vegetables, raises chickens, reads the newspaper in the morning, and rides his bicycle around the barangay in the afternoon. Occasionally, he calls to show off the vegetable beds behind the house, telling me to go get chickens and eggs for my grandson to eat. I ask:

— “Does Tatay feel regretful about working hard all his life for his son?”

He laughs:

— “No regrets. Tatay has worked all his life—but the thing he is most proud of is building a son like you.”

I don’t answer. I just watch his hands on the screen—the hands that carry my future.

I am a PhD. Mike is a construction worker. He didn’t build a house for me—he “built” a person.