PART 1: THE CITATION

The elderly woman cited for selling produce stood at the corner of Maple Ridge and Seventh Avenue just after dawn, her wooden cart angled carefully where the sidewalk dipped and a strip of shadow kept the early heat from settling in. The cart was narrow and patched together, its metal brackets bent inward as if they had been straightened and bent again more times than anyone could count. Bundles of greens lay on top, along with a handful of tomatoes and two sacks of onions, each rinsed and wrapped in yesterday’s newsprint. Nothing about the scene suggested defiance or stubbornness. It looked like endurance, quiet and practiced.

Her name was Ruth Calder, seventy-nine years old, born in Kansas and raised across three Midwestern towns she never truly left behind. Each morning she walked seven blocks from her apartment with the cart tugging at her hip, stopping once near the pharmacy to rest and again beside the bus shelter to steady her breathing. She arrived before the city fully shook itself awake, before horns and rules overlapped and hardened. People who passed recognized her face without knowing her life. A few smiled. A few bought a tomato. Most drifted by as if she were part of the curb.

The patrol car slowed before she noticed it, tires brushing the gutter with a hushed scrape. Officer Lucas Bennett, thirty-one and newly into his second year wearing the badge, stepped out with a tablet in hand and a schedule already behind him. A complaint about an unlicensed vendor had pinged twice on his screen, and his sergeant had emphasized that compliance numbers mattered this month. He approached with a neutral expression practiced into place.

“Ma’am,” he said, his voice even as his eyes traced the cart’s contents. “You can’t sell here.”

Ruth lifted her gaze slowly, gray-blue eyes clear though rimmed with age. “I’m not causing trouble,” she replied. “I’ll be gone soon.”

Lucas exhaled, the sound small and restrained. “I hear you, but you need a permit. I have to issue a citation.”

She nodded as though she had been waiting for the word to arrive, fingers tightening along the cart’s edge. “How much is it,” she asked, her tone steady despite the tremor that began in her wrist.

“Seventy-five dollars,” he answered. The figure settled between them like a weight neither could move.

Ruth blinked once, then reached into her coat pocket and withdrew a cloth pouch tied with twine worn soft by use. She loosened the knot with deliberate care, tipping its contents into her palm. Coins spilled out, quarters and nickels and pennies, the sound of them light and uncertain against her skin. Her hand began to shake, not from the morning chill but from something deeper, and the coins slid through her fingers to the concrete below.

She murmured a word then, a name carried like a reflex. “Michael.” The pouch slipped from her grasp, scattering change that rolled toward the curb. She bent too quickly, her knee buckling as she caught herself against the cart, breath hitching sharp and fast. Lucas froze, aware of eyes gathering and a phone lifting nearby, aware that no training module had prepared him for this moment.

“I don’t have that much,” she said softly. “I thought maybe today would be enough.” He could still cancel the citation if he chose, or he could finish the process he had started. Clearing his throat, he extended the tablet and recited the procedure. “You’ll receive a notice by mail,” he said. “You can contest it in court.” Ruth nodded again, nodding as if it cost less than pleading. She knelt to gather the coins with shaking fingers while Lucas stepped back, then turned and walked away without looking at the cart, the vegetables, or the woman who remained on the ground long after the cruiser disappeared.

PART 2: WHAT THE CITY MISSED

The elderly woman cited for selling produce did not return home that morning. Ruth stayed beside the cart, sitting on a low retaining wall with her hands folded in her lap and her eyes fixed on a point no one else could see. The vegetables sat untouched, their bright colors dimming as the sun climbed. She no longer called out, no longer lifted her head when footsteps passed.

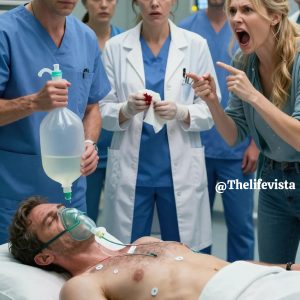

Two hours later, she collapsed. An ambulance arrived, paperwork followed, and a brief assessment labeled the cause as dehydration, exhaustion, and low bl00d sugar. She was released before dusk with instructions she nodded through and no questions asked about the name she had whispered on the sidewalk. No referral was made. No one lingered.

Someone else, however, had been paying attention. Isabel Moreno, a neighborhood reporter walking toward her office that morning, had noticed the gathering crowd and the sound of coins tapping concrete. She had not filmed, having grown tired of turning pain into clips, but the image stayed with her. When the scanner crackled with a call from the same block later that day, a knot formed in her chest that would not loosen.

Isabel found Ruth’s address the next afternoon in a building slated for refurbishment. Ruth opened the door slowly, wary but courteous. “Am I in trouble,” she asked, her voice thin with uncertainty.

“No,” Isabel replied. “I just want to hear your story.”

Inside, the apartment was orderly and spare, the air smelling faintly of soap. A single photograph rested on a shelf, showing a young man in a hard hat with his arm around Ruth’s shoulders, both of them smiling. “My son,” Ruth said when she noticed Isabel’s gaze. “Michael.” He had d!ed six years earlier in a construction accident, leaving behind medical bills that consumed her savings before he was gone. Selling vegetables was what remained, and the name she spoke when frightened was not a prayer but a habit of speaking to him.

“I never meant to break any rules,” Ruth said, folding her hands together. “I just needed the day to turn out right.” Isabel’s article went live that evening, naming no officers and leveling no accusations, simply telling the story of an elderly woman cited for selling produce and the moment her hands shook enough for the city to finally look. By morning the comments multiplied, by afternoon the department issued a statement about procedure, and by nightfall the mayor’s office requested Ruth’s address.

PART 3: WHEN THE CHANGE STOPPED DROPPING

The elderly woman cited for selling produce woke to a knock that carried a different weight. Lucas Bennett stood in the hallway with his cap in his hands, uniform neat and eyes shadowed by sleeplessness. He had read the article repeatedly, each time seeing the coins again.

“I’m sorry,” he said quietly. “I should have done better.” Ruth studied him for a long moment before answering. “You did what you were told,” she said. “I was just worn out.” Lucas nodded, swallowing as he explained that the citation had been voided and more had followed. The city waived the fine, a nearby grocer offered her a seated position indoors for three mornings a week, and donations arrived in amounts Ruth accepted only as needed.

What stayed with her was not the money but the listening. Weeks later the corner of Maple Ridge and Seventh stood empty, yet people slowed when they passed, remembering the sound of change and the story that had traveled farther than the sidewalk. The city amended a policy with a quiet line about discretion, Lucas transferred divisions, and Ruth visited her son’s grave with tomatoes in her hands, speaking his name without the tremor that once betrayed her fear. Somewhere in a municipal database the entry remained, but the meaning had already moved beyond it, carried by those who had finally seen her.