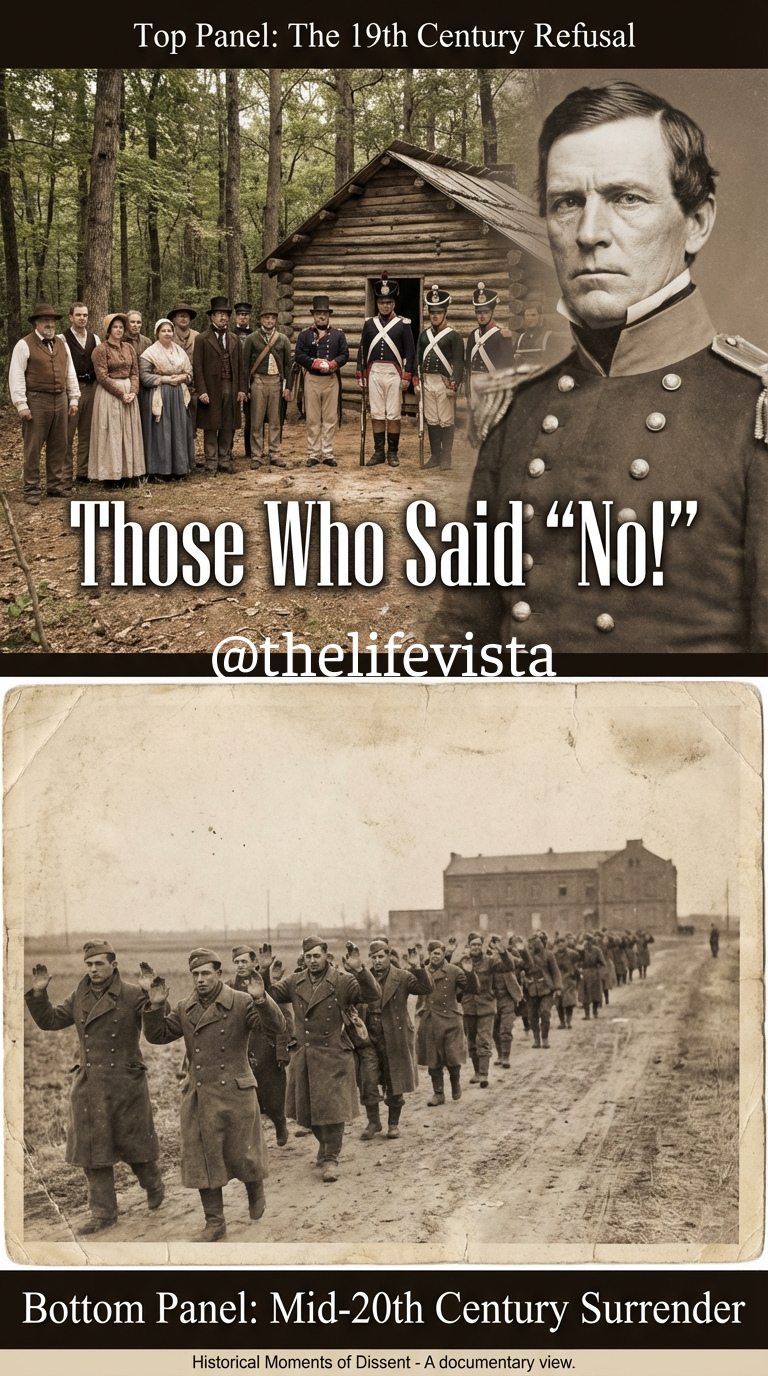

Imagine standing in a firing squad in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe. The order comes: “Shoot the civilians.” But one soldier steps back and says no. What happens next? Most of us assume he’d be shot on the spot… In this video, we uncover the stories of soldiers and officers who refused to kill and what consequences they faced.

Good to have you back on the channel. If you’re new: my name is Stephen; I’m an American history teacher and I make videos about history for you. If you like that, please consider subscribing and don’t forget to hit the notification bell. You can support me via Patreon, PayPal or via a SuperThanks.

Let’s start! During World War II, it was widely believed among soldiers, officers, and police personnel that every order from a superior had to be obeyed no matter what. Disobeying could supposedly lead to death, imprisonment, or even danger for one’s family. Many historians have long shared this view.

But was it truly impossible for a soldier to refuse to take part in the murder of civilians and still survive? Could one say “no” without being executed or sent to a concentration camp? While it’s difficult to know every case due to limited documentation, historian David Miller uncovered over a hundred verified instances where individuals refused to shoot unarmed civilians or prisoners.

What happened to these soldiers? Miller’s findings come from detailed postwar investigations and trial records held in state archives and the Central Office for Investigation. Drawing on these records, Miller documented at least eighty-five confirmed cases of refusal, expanding on earlier research.

Miller’s study not only examined what happened to those who refused but also how they resisted, why they made that choice, and what legal and personal factors influenced their decisions. His work sheds light on a rarely discussed aspect: that some individuals, even within the machinery of terror, found the courage to say no.

Dr. Albert Baxter, a lawyer and reserve major in the Army, used his military authority to try to stop the security forces in Przemyśl from carrying out a so-called “resettlement”—an operation that was, in reality, a mass execution. Born in 1891, Baxter joined the party on May 1, 1933, at age 42, and also belonged to the National Socialist Lawyers’ League.

A Catholic, he had previously lent money to a Jewish colleague in 1936–1937, an act that led to a denunciation within the Party. As punishment, he was formally reprimanded and his membership was suspended for a year. Investigations later revealed that Baxter had shown willingness to help victims even before the war.

On July 24, 1942, Baxter persuaded his superior officer, Major Logan, to issue an order placing workers employed by the military under protection: “In view of the previous actions, the local commander gives orders to bring all workers into barracks and place them under military protection. They are to be fed and housed, etc., so that they remain able to work.”

Baxter then took direct action: blocking bridges across the river to prevent security units from entering the area, and evacuating 80–100 people from the ghetto to the army headquarters. Although this defiance only delayed the deportations, Baxter’s intervention temporarily saved their lives.

His actions drew complaints to the high command, who personally ordered an investigation. Baxter was eventually reprimanded and transferred to a front-line unit, and leadership even planned to have him arrested after the war. Baxter survived the conflict and was later recognized for his courageous stand.

His deeds went beyond simply refusing orders; they represented direct resistance to operations, all while facing remarkably mild punishment for such defiance. Bernard Gray managed to avoid taking part in the execution of civilians by strictly following military protocol and immediately protesting to his superiors.

Born in 1887, he had retired in 1936 as a major in the Order Police. When war broke out, he was recalled to service and became acting commander in his region. In early 1941, he trained a recruit battalion which later operated under his command.

Gray’s unit was subordinate to the regional headquarters. At one point, an officer personally asked Gray to provide men for an execution of civilians. Gray refused. He ordered his senior captain to stay at headquarters and forbade anyone in his battalion from participating without his direct authorization.

He then traveled to the regional capital to secure a written confirmation from his superiors that he was only to follow orders issued directly through official channels. He obtained such a document. This move effectively blocked the request, forcing the other units to carry out the execution themselves while Gray was away. Although an investigation was opened into his refusal, it was dropped after Gray gave testimony at the main office.

Remarkably, soon after this episode, Gray was awarded a high military honor, despite having openly resisted involvement in mass executions. There are other similar cases of officers who protested against the fact that their men were about to be used for mass executions. In one instance, an order came directed at all units that they were not to be involved in executions.

A remarkable case of formal refusal by two officers took place in Poland in late June and early July 1941. Frederick Dean, commander of an escort battalion, received orders to send one of his companies to a meeting point for further instructions.

The detachment, led by Second Lieutenant Scott, rejoined the main battalion later that evening. Scott reported to Dean that part of his company had been forced to take part in the execution of civilians earlier that day. He told his commander he refused to carry out any more such executions, adding that he would not compel his soldiers, trained as combat troops, not killers, to participate again.

That same evening, Dean wrote to the leadership office, clearly and explicitly stating that he would not allow his battalion to be used for executions in the future. His report included Scott’s written account of what had occurred. Within days, the office ordered the immediate dissolution of the entire battalion.

Its companies were reassigned to various other regiments. Dean was summoned to report personally to General Parker, who reprimanded him for disobeying orders but did not punish him further. Instead, Dean was reassigned as a major; he was later promoted to commander of a different battalion and held high posts until the end of the war.

Despite his open defiance of directives, Dean faced no serious consequences and continued serving in high command positions throughout the war. One particularly striking case involves an officer who refused to take part in executions and consequently spent about three years in a concentration camp.

The officer was Dr. Nicholas Horn, a lawyer and first lieutenant in the military, who had previously served in the police. In October 1941, Horn was sent east as a platoon leader. On November 1, 1941, his battalion commander ordered him to execute 780 prisoners. The plan was to kill them in a small forest.

Horn refused to carry out the order, explaining to his commander that as a lawyer, a Catholic, and an army officer, he could not participate in such an act. He assembled his men and informed them of his refusal, telling them that shooting defenseless people was a crime.

None of his men took part in the killings, though they were ordered to guard the perimeter. Soon after, Horn was recalled and arrested in May 1942 on the orders of Judge Justin Waldeck. He was charged not primarily for disobedience but for “undermining military morale” by setting an example that might encourage refusal among others.

His first trial resulted in a sentence of three to four years in prison; a second trial in 1945 increased the sentence to six or seven years. During this time, Horn was imprisoned in a concentration camp. Because Horn based his refusal on military law, leadership reportedly considered the sentences too lenient and refused to sign them.

As a result, Horn was treated unusually well for a prisoner: he kept his officer’s rank and pay, and his detention was classified as “investigative arrest” rather than punishment. Horn remained in the camp until the end of the war. His imprisonment was not for refusing to shoot, but for teaching his soldiers that military law gave them the right to reject illegal orders.

Miller investigated 85 cases from individuals ranging from every level of the armed forces: from generals and police to officers and enlisted men. Almost half of the time the reason for refusal was not given. A quarter of the cases were based on conscience. Fifteen times it was seen as illegal. Others believed it caused emotional disturbance. Some claimed it was not within their role and two claimed the murders were politically disadvantageous.

Out of 85 documented cases, over half involved direct refusal, with some men formally protesting to superiors to protect themselves from future involvement. Others relied on moral, religious, or psychological reasons. A few invoked international law or military codes, while others faked illness or incompetence to evade participation.

Knowledge of legal procedures helped officers more than enlisted men; officers made up roughly two-thirds of successful refusals. Some demanded legal proof before agreeing. Others sought transfers to combat units or used creative evasions like hiding during shootings or missing on purpose. A few soldiers even threatened force when coerced.

In the book Ordinary Men by Christopher Brown, a battalion under Major William Trapp was ordered to round up 1,800 civilians. This time, only men capable of work would be sent to labor camps; the women, children, and elderly were to be executed on the spot.

One officer, Lieutenant Henry Buchman, a 38-year-old businessman and reservist, was horrified. He told Trapp’s adjutant that he refused to take part in the shooting of defenseless civilians and requested another duty. He was reassigned to escort the men selected for labor instead. Before the massacre began, Trapp assembled his men and remarkably offered any who couldn’t bear the task the chance to step aside. Only a dozen men accepted his offer.

So what were the general consequences for those who refused? Of the investigated cases, not a single person lost his life because of his refusal. In more than half of the cases, there was no negative consequence at all! Reprimands or threats happened in a dozen cases, as well as transfers.

In one instance, a person was sent to a camp, but as discussed before: this was for teaching his soldiers about their rights, not just the refusal itself. In a handful of cases, they were sent to combat units or received house arrest. Demotion or forced resignation did occur as well.

This doesn’t mean that severe punishment was never meted out. There is the case of Joseph Schultz, a soldier who allegedly refused to take part in an execution and was shot with the hostages. However, historians dispute the story, and some consider it to be a legend rather than fact.

There is also the case of Otto Simon, a soldier who served on a firing squad. He was reportedly executed for refusing to participate, and has become a symbol of opposition. However, the accuracy of this account has been questioned due to lack of credible evidence.

An interesting case occurred in the occupied Netherlands where a soldier was ordered to shoot resistance fighters. He refused and did NOT live to tell about it. Wonder what happened? Click here for my video about that tragic event. Thanks for watching and the History Hustler is signing off.