The alarms in Trauma Bay Two were screaming nonstop, filling the air with urgency. Beyond the curtains, Alamo Heights Medical Center was in controlled chaos after a devastating highway accident involving a military convoy. Inside the bay, however, Dr. Jordan Hale stood as the calm eye of the storm. Her movements were swift and precise—clamping vessels, issuing instructions, making split-second decisions—while Dr. Ethan Ward, the ER chief, worked desperately to keep up. She didn’t raise her voice or demand attention. She simply worked, focused and unshaken, her scrub cap pulled low, giving no hint of who she truly was.

Then the doors slammed open, and everything changed.

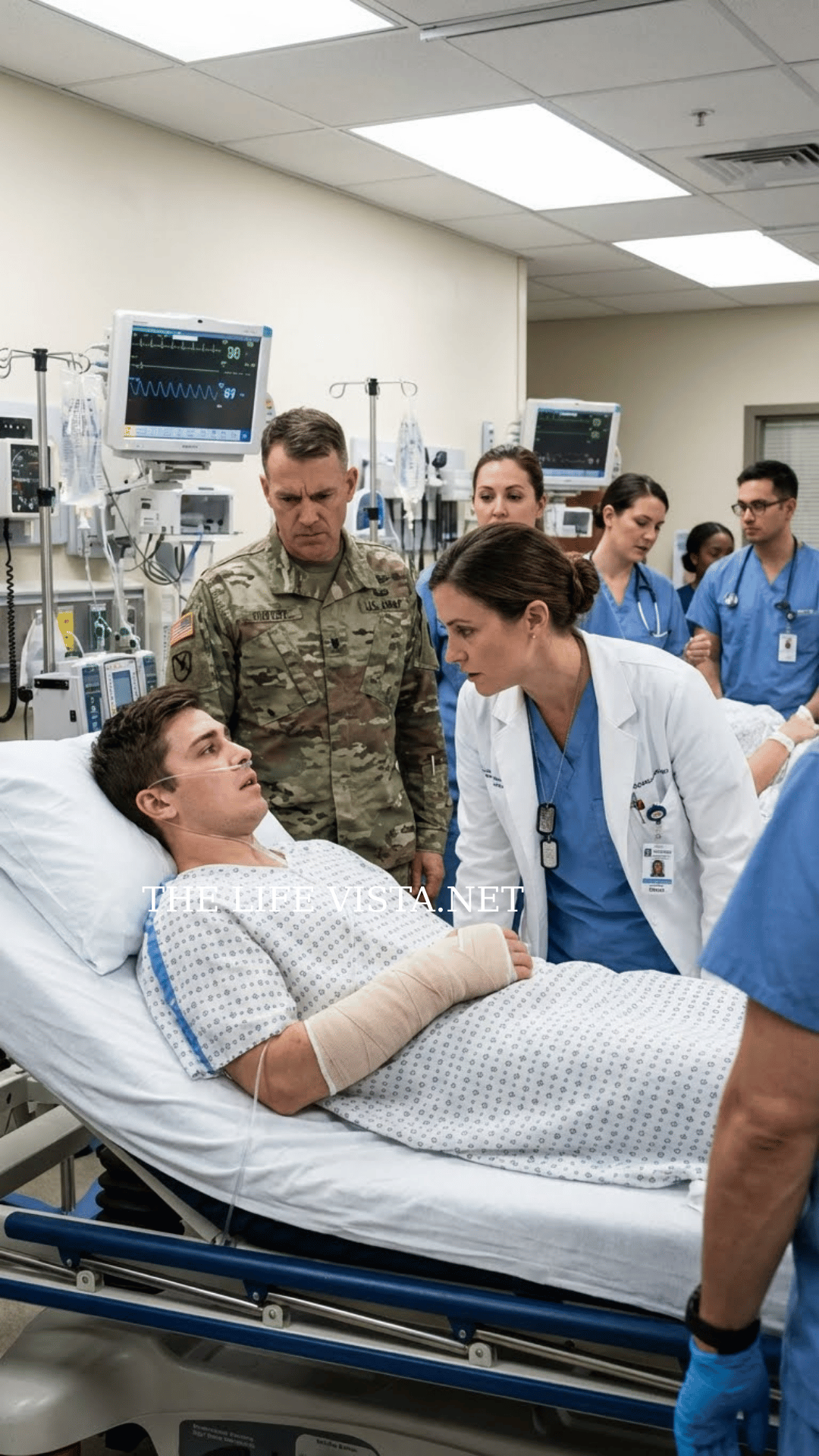

General Barrett didn’t enter the room so much as dominate it. Accompanied by visibly anxious aides, he scanned the scene with an authority that silenced conversations. He took in the blood, the frantic motion, the overwhelmed staff—and then his eyes landed on his son, Lieutenant Ryan Barrett, lying broken on the gurney.

“Status,” the General demanded sharply. “Where is the attending? Where is the specialist?”

A nurse began to answer, but Barrett cut her off instantly.

“I don’t want reassurances,” he snapped, anger rising as he looked at his injured son. “I want the best surgeon in this hospital. I will not leave my son in the hands of second-rate staff.” His gaze settled on Jordan’s back, and he dismissed her without a second thought. “You—move aside. Get me a real surgeon.”

The room fell into stunned silence. Ethan went pale. But Jordan didn’t move. She didn’t even turn around. Her hands were still deep in the procedure, holding back catastrophic bleeding through sheer skill and control.

“I am the attending,” she said evenly. “And you are standing in my light.”

The General stepped closer, fury radiating from him. “I asked for a surgeon, not someone pretending to be one. Step away now, or I’ll have you removed.”

That was the moment everything shifted.

Jordan slowly turned her head. Her eyes held no fear—only the hardened calm of someone who had faced far worse than an angry general. Something in her stance, her presence, made Barrett hesitate. This was not a woman out of her depth.

On the bed, Lieutenant Ryan Barrett fought through the fog of pain and medication. His arm lifted weakly, fingers moving toward his brow in a motion his father didn’t understand—but one that meant everything to the woman saving his life.

At a quarter to six, the emergency department at Alamo Heights Medical Center looked like it had never gone to sleep. Fluorescent lights hummed above scuffed linoleum, washing everything in the same thin white. The air smelled of antiseptic and burned coffee.

Dr. Jordan Hale stood at the nurse station with a cardboard cup between her hands, eyes on the bedboard. The coffee was already cooling, she drank it anyway. Her badge read, Trauma Surgery Attending, in small black letters that no one seemed to notice.

When she shifted her grip, her sleeve slid back. A loop of dull metal showed at her wrist chain links and a small rectangular plate pressed to her skin. The letters stamped into it were softened from wear.

She pulled the fabric down again. Across the counter, Dr. Ethan Ward told a story. So this guy rolls in pressure in the 70s belly hard.

He said one hand sketching the curve of an abdomen. Radiology wants a CT. I tell them if we wait 10 minutes, we lose him.

Straight to the OR. Spleen in pieces. Clamp pack, done.

He’s probably arguing about the food by now. A couple of nurses smiled. A first year shook his head, impressed.

Rick Halpern, chief resident, glanced up from his tablet, just long enough to smirk. That why you look like hell, Rick asked. Ethan tilted his head.

You should see the other guy. Laughter rippled around the station. It washed past Jordan.

She remembered the mottled bruise on that patient’s flank, the way she had murmured retroperitoneal bleed. He needs the OR and the quick nod Ethan had given before repeating it louder. Dr. Hale.

She turned. Halpern had stepped close her tablet, balanced in his hand. Yeah, she said.

Bed 8, he said. Forearm laceration. Needs closing.

We are short-staffed and the intern is tied up upstairs. Can you take it? Sure. Appreciate it.

His eyes were already back on his labs. It landed like a small favor he had just granted her. Carla Morales slid a chart toward Jordan as she rounded the counter.

Carla’s badge had been swiped so often the plastic was cloudy. Walk in from a job site, Carla said. Cut his arm on rebar.

Blood everywhere. I cleaned what I could. Any numbness, Jordan asked.

He says no, Carla replied. He also says he has to be back on site by 7. Jordan nodded and took the chart. The hall beyond the station was a line of curtained bays and blinking monitors.

Air from the vents brushed the back of her neck cooler near the ambulance doors. The curtain at bed 8 bowed inward. She hooked it aside with her elbow and stepped in.

The man on the gurney wore a neon yellow safety vest over a dark t-shirt. His jeans were dusted with gray powder. A hard hat sat on the chair.

His uninjured hand held a phone. His thumb did not stop moving when she entered. Morning, Jordan said.

Hey, Doc. He glanced up then back at the screen. You doing the stitches? I really need to get going.

Let me see your arm first. He sighed then held it out. The gauze clung to dried blood.

She loosened the tape and unwound it. The cut ran across the top of his forearm wide enough to gape deep enough to show the pale shine of tendon under fat. The edges were ragged.

She bent closer. One of the extensor tendons was clearly damaged. Near it a pale cord lay too close to the surface.

Any tingling, she asked. Pins and needles, numb spots. Nope, he said.

Feels normal. They just freak out when they see blood. Lift your wrist, she said.

He tried. The motion was there but weaker than it should have been. Close your eyes, she said.

Tell me if this is sharp or dull. She touched his hand and forearm with the tip of a cotton swab. His answers lagged.

A couple were wrong in a pattern she recognized. You are not going back to work today, Jordan said. His eyes opened.

Come on. It is just a cut. It is deep, she said.

You may have some nerve involvement. I’m going to call hand surgery. He laughed once.

Hand surgery? For this. The clinic by our yard does stitches all the time. I do not need a specialist.

Today you do, she said. If we do not fix this right, you could lose strength in that hand. How long you been doing this, he asked.

Long enough, she said. She laid fresh gauze over the wound, wrapped a clean dressing, and secured it. He flinched once and then watched her fingers closely.

I will have someone bring you something for the pain, she said. The hand surgeon will see you soon. She stepped out.

The curtain slid back into place. At the station, she picked up the phone and paged the on-call hand surgeon. Forearm laceration, likely tendon, and radial nerve involvement, construction worker, she said.

Would appreciate an evaluation. She hung up. Ethan’s voice drifted from the other side of the counter.

She just called a specialist on a forearm lac, he said. Cautious, Rick replied. She overcalls everything.

Carla walked past with an IV tray. Her gaze met Jordan’s for a heartbeat, then moved on. Jordan sat at the terminal, logged in, and opened the chart.

The cursor blinked on an empty field. She typed in tendon exposure weakness on extension inconsistent sensation consult placed. Her coffee waited beside the keyboard.

She took a sip. It was cold now, the taste flat and bitter. Somewhere above, a helicopter engine rose.

The vibration ran down through the ceiling tiles into the floor under her shoes. She listened for a moment, then dropped her eyes back to the screen and moved to the next name on the list. The next few hours blurred into the usual rhythm of the shift.

Labs came back, orders went in, families asked the same three questions in different voices. The board filled, emptied, filled again. By mid-morning, the whiteboard at the station had a red star next to bed three.

Carla had written motor vehicle collision chest pain, decreased breath sounds in a tight hand. Someone had circled it twice. Jordan walked toward the bay paper gown rustling against her scrubs.

Behind the curtain, a young man lay propped against the head of the bed, skin the color of paper. His t-shirt was half cut away. A bruise spread across the left side of his chest, the pattern of a steering wheel faint under the discoloration.

Dr. Aaron Lynn stood at his right side, stethoscope in his ears, brow furrowed. He was slim, dark-haired, with a face that still looked more like a student than a doctor. A senior resident hovered near the foot of the bed, arms crossed.

Breath sounds, Jordan asked. Aaron looked up startled. Diminished on the left, he said.

Trachea is midline. Some jugular distension. Pressure is 90 over 60.

He is pretty tacky. Jordan stepped closer, listening for the rasp of air watching the rise of the ribs. The left side rose less than the right.

Each inhale made the bruise darken at the edges, as if something underneath was pushing back. We are doing a chest tube, the senior said. Lynn, walk me through your landmarks.

Aaron swallowed. His gloves squeaked as he felt along the ribs counting under his breath. Mid-axillary line, he said.

Fifth intercostal space. Jordan watched his fingers stop a little too high. She could hear the helicopter again faint through the ceiling, the chopper blades a steady chop in the background.

For a moment, her body thought of another tent, another field, but she forced the thought aside. Aaron, she said, keeping her voice low. That is the fourth.

He did not look at her. I checked, he said. I am on five.

The senior resident did not intervene. He took a half step back, leaving space. Jordan frowned, fingers tightening around the bed rail.

The nurse clipped the sterile drape into place. The room contracted to a square of exposed skin and blue paper. The smell of chlorhexidine hung heavy.

Aaron made the incision. The man on the bed flinched. The first cut was fine.

Then the clamp went in, pushing through subcutaneous fat and muscle. Jordan’s gaze tracked the angle of the instrument. She saw it before it happened, the slight shift too close to the inferior edge of the rib, where the intercostal artery hugged bone.

Bright arterial blood burst up around the clamp, a sudden spray that painted Aaron’s gloves red to the wrists. Shit, he whispered. The monitor beeped faster.

The man’s pressure started to slide down, clamped Jordan said. Her hand was in the wound before anyone answered. Warmth closed around her fingers.

Bone under her knuckles, slippery tissue, the fast hammer of an artery. She pressed where the beat was strongest. The bleeding slowed, then pulsed against her fingertips.

Long hemostat, she said. The scrub nurse slapped it into her palm. Jordan followed the pulse by feel guiding the tip, closing it around the vessel.

Tie, she said. The suture brushed her glove. Two throws, three, cinched down tight.

The artery went still. You’re going to reposition your tube, she told Aaron, not looking up. Below the rib.

Higher posterior if you can. Aim for the apex. He nodded Adam’s apple bobbing.

His breathing was loud in the small space of the drape. This time he counted more carefully. The tube slid into the chest and a stream of air rushed out, followed by a slow trickle of dark blood.

The man’s chest rose more evenly. The monitor settled. Jordan stepped back and stripped off her gloves.

Blood clung to the cuff of her sleeve in a dark crescent. Next time, she said quietly to Aaron, find your landmarks twice before you cut. He stared at his hands.

I thought I had it, he said. I know, she replied. You will remember this one.

She left the bay. The noise of the hall rushed in phones ringing shoes on tile. Carla caught her eye as she passed her gaze flicking down to the stain on Jordan’s cuff.

You want me to grab you a fresh top? Carla asked. In a minute, Jordan said. The locker room was empty except for the sound of a shower running behind a closed stall.

Fluorescent light bounced off the metal doors. The air held the faint smell of soap and sweat. Jordan turned the faucet at the sink all the way to hot.

The water stung as it hit her skin pink swirling down the drain. When she looked up, the mirror showed a face she recognized. And for a heartbeat, one she did not.

The same dark eyes, the same pull of her mouth, but framed by canvas walls and hanging IV bags by a cot in the corner and a stretcher half out of frame. She blinked. The reflection shifted back to gray tile and blue scrubs.

She opened her locker. The Polaroid sat in the corner tilted where she had left it. Six figures in dusty uniforms, helmets, off faces.

Streaked eyes, half laughing, half exhausted. The edges of the photo were cracked. She hesitated, then tucked it a little further back as if distance could soften the focus.

A helicopter thudded somewhere above, shaking a few specks of dust from the vents. Her pager went off on her hip. She closed the locker and headed back down.

By late afternoon, the department had that brittle quiet that meant the calm would not last. The board was half full. A couple of patients slept with open mouths monitors counting for them.

Jordan was at a terminal reviewing labs when the radio squawk came from the EMS base. Alamo Heights, this is medic 12. Inbound with one male, early 20s, single, GSW to the left, chest decreased.

Breath sounds hypotensive, GCS 10, ETA 4 minutes. Carla reached for the trauma bay switch without waiting to be told. The red light over trauma one snapped on.

Ethan appeared at Jordan’s shoulder. I will take it, he said. OK, she said.

There was no argument in her voice. She logged out and walked with him to the bay. Trauma one was already half prepared.

A ventilator stood ready in the corner. A tray of gleaming instruments waited by the wall. The smell of plastic and bleach was sharp.

Jordan pulled on a lead gown, then gloves. The room filled with people in blue and green. The doors from the ambulance bay banged open.

The gurney came in fast wheels rattling. The paramedic at the head called out words clipped. 22-year-old male, GSW, left anterior chest.

Just medial of the nipple line. Found on the sidewalk. No exit wound.

Pressure on last check was 80 over 40, heart rate 140. We have given one unit of blood in the field. The patient groaned as they moved him.

His skin was slick with sweat. His eyes were half open, irises a dark brown that barely showed between the lids. Jordan stepped in to take his airway.

Her fingers found his carotid. The pulse was thready and too fast. On my count, she said, one, two, three.

They slid him across onto the hospital bed. The paramedic kept his hands pressed against the dressing over the wound until Jordan replaced them. Ethan took his stethoscope, listened to both sides of the chest.

Breath sounds diminished on the left, he said. He needs a tube. Carla read out numbers.

Pressure, 70 over 38, pulse 150. Sats 82 on non-rebreather. The room tightened.

Ethan moved to the side, searching for landmarks, tracing ribs with gloved fingers. He paused reposition, checked again. Jordan watched the color of the patient’s lips, a faint bluish line forming at the edges.

Veins on the neck stood out with each struggle of the heart. Her tongue tasted of metal, the same ghost of taste that came with every big bleed. Ethan picked up the scalpel.

His movement was textbook. Incision blunt dissection, the slow widening of the path to the plural space. It was good.

It was also slow. The monitor alarm began a continuous tone. Carla called the numbers again.

60 over palp only. Sats 78. The patient’s eyes rolled back slightly.

He’s dropping, someone said. He will be fine, Ethan answered, but his hands hesitated for half a beat. The half beat was enough.

Move, Jordan said. She did not raise her voice, but the room shifted. Ethan stepped back, almost on reflex.

His eyes startled. The nurse at the instrument tray did not ask who she meant. Jordan took the scalpel.

The skin yielded. She widened the incision with a swift practiced motion, spread the ribs with her fingers. Her body moved ahead of thought.

Thoracostomy tray, she said. The rib spreader clicked as it opened. The small chest cavity appeared in the gap, slick with blood.

It pooled and sloshed with each failing heartbeat. Suction roared. Dark fluid left the chest and sheets the vacuum canister filling almost at once.

She saw it a pulsing jet from a tear in the pulmonary artery, each beat pushing life out in spurts. Clamp, she said. The instrument warmed quickly in her hand.

She slid her fingers around the artery, closing off the leak. The jet slowed, then stopped. The room quieted to the hiss of the ventilator and the soft beeping of the pulse ox as it began to climb again.

90 over 50, Carla called. Sats climbing. 82, 87.

Jordan placed sutures with small economical movements. Tie cut, tie cut. The vessel held.

The field cleared. She checked again, making sure no other source of bleeding hid behind the lung. When she was satisfied, she nodded to anesthesia.

He is all yours for now, she said. She stepped back, feeling the pull of the lead gown on her shoulders. Her gloves were red up to the cuff.

The room smelled of iron and plastic. Ethan watched her jaw tight. Something like shock in his expression.

The nurse at the foot of the bed avoided her eyes fussing with lines and leads. Jordan peeled off her gloves and let them fall into the biohazard bin. Her hands were pale, where the latex had gripped her skin.

In the scrub alcove, she turned on the water again. This time it was lukewarm. She scrubbed at the spaces between her fingers until the pink tinge faded.

Drops of water slid down her forearms and dripped onto her shoes. She stared at her reflection in the small metal panel above the sink. The face that looked back at her was the same, but her eyes had that distant flat look she knew so well from the tent.

The overhead intercom crackled, announcing a visitor at the front desk. Somewhere above the muted thud of rotor blades started again a low vibration that traveled through the walls. Jordan closed her eyes for a second, then opened them and reached for a fresh towel.

She dried her hands, straightened her scrub top, and stepped back into the bright, humming light of the hall. The afternoon light had shifted by the time the adrenaline bled out of her system. It came in low through the narrow windows high on the far wall, turning the dust in the air into a moving haze.

Jordan sat in the break room with a fresh cup of coffee in front of her, and a protein bar still in its wrapper beside it. The clock over the microwave ticked with a plastic click every second. Someone had left the television on with the sound muted.

A news anchor moved their lips around words she could not hear. Her hands were still faintly damp from the scrub sink. When she wrapped them around the cardboard cup, the warmth made the skin sting.

The door opened without a knock. Ethan stepped in, untying his lead apron as he walked. He tossed it onto a chair and leaned his shoulder against the fridge.

That was fast work, he said. Jordan did not look up yet. Steam rose from her coffee in a thin waver.

He did not have time for slow, she said. Ethan rubbed at the back of his neck. The usual easy grin was missing.

He seemed to be searching for it and coming up empty. I had it under control, he said after a moment. Or I thought I did.

You had the right idea, she said. You just did not have the minutes. He let that sit between them.

On the TV, a graphic showed a map with colored lines. The anchor gestured at it, still silent. I’m going to check on him in the ICU, Ethan said.

You coming? In a bit, Jordan replied. He nodded, pushed off the fridge, and left. The door swung shut behind him with a soft thump.

The clock went back to being the loudest thing in the room. She took a sip of coffee. It burned her tongue.

She swallowed anyway. Someone laughed out in the hall, then hushed themselves mid-sound. The break room door opened again halfway as if whoever was on the other side was not sure they should be there.

It was Carla. You hiding, Carla said. Jordan glanced at her.

Just sitting. Carla stepped in far enough to reach the counter, grabbed a clean mug, and poured coffee from the pot that looked like it had been left on since sunrise. You have people talking, Carla said.

About what, Jordan asked. Carla looked at her over the rim of the cup as she took a sip. About trauma one, she answered.

About how you cracked that kid’s chest like it was a routine appy. Jordan stared at the table. It was not routine, she said.

I know, Carla replied. They do not. She put the mug down, wiped a ring of coffee off the counter with the heel of her hand, then straightened.

Radiology is calling about that older guy with the GI bleed, she added. They want to know if you are still planning to scope him in the ED or send him upstairs. I will come by, Jordan said.

Carla nodded and left. The door closed with the same soft click. Jordan unwrapped the protein bar without any real intention of eating it.

The chocolate coating cracked under her fingers, leaving smears on the wrapper. The intercom crackled overhead. Security to main lobby, a voice said.

Security to main lobby. She did not think anything of it at first. Security went to the lobby for lost children, angry relatives, people who refused to keep their voices down.

Five minutes later, the door opened once more. This time, the man who stepped through did not belong to the hospital. He wore an army combat uniform, sleeves rolled to the regulation point, just below the elbow.

His boots were scuffed but polished. The name tape over his chest read, O’Neill. Chevrons and rockers on his sleeve marked him as a sergeant first class.

There was a small white scar along his jaw, a faint line that caught the light when he turned his head. He stopped just inside the doorway and stood still, like he had just spotted something he had been looking for and was not entirely sure it was real. Excuse me, he said carefully.

I am looking for Dr. Hale. This is staff only, Jordan said. Family waiting is down the hall.

I know, he answered. Security brought me back. They said she was in here.

She lifted her eyes fully to his face. He held her gaze. His eyes were green with lines at the corners that had been carved by sun and squinting.

He stared the way patients stared when they were trying to place a face from a different life. Dr. Jordan Hale, he said, trauma surgeon. She felt her back stiffen.

You have got the right name, she said. I am busy though. If you need help finding someone, the desk can… That is not all of it, he interrupted softly.

Major Jordan Hale, forward surgical team. The room went very quiet. Even the clock seemed to pause.

He took a step closer, moving slow, like he was approaching a wild animal. Ma’am, he said. The word came out in the old way from habit flattened a little at the end.

Camp Lawson, June 2015. You held my femoral artery in your hand for 40 minutes while they tried not to bleed me out on the floor. The coffee in Jordan’s stomach went heavy.

For a moment, she could smell the dust, the metallic tang of blood mixing with sand, feel the oppressive weight of heat under canvas. You have the wrong person, she said. He let out a small breath that was almost a laugh.

You told me to stay with you, he said. You said stay here, Sergeant. I am not done with you yet.

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a worn blue folder. From it, he slid a photo, the glossy kind printed from a phone. It showed him on a hospital bed, leg wrapped from hip to knee, his face puffy, but very much alive.

A woman in scrubs and a surgical cap stood at his bedside, arms folded. The image was grainy, but her eyes were unmistakable. He placed the photo on the table between them.

Long time, ma’am, he said. Jordan looked at the picture without touching it. The woman in it looked younger, with fewer lines around her mouth, but the set of her shoulders, the slight tilt of her head were the same.

A shadow darkened the doorway. A unit clerk passing by had glanced in and paused. She lingered just long enough to see the uniform, the photo on the table, and the way the man was standing.

You have the wrong person, Jordan repeated. Her voice sounded thin to her own ears. He shook his head.

Marcus O’Neill, he said, tapping his name tape. 3rd Battalion, 5th Infantry. We hit an IED outside Lawson, took my team’s medic and half my quad.

I remember Dustin screaming, and then you right in the middle of it, up to your elbows in blood, you had a headlamp on and a cigarette tucked behind your ear that you forgot about. You said if I bled on your boots, I owed you a new pair. His mouth curled a little at the memory.

I woke up at Landstuhl with my legs still attached, he went on. Everybody kept talking about the miracle surgeon out in the dirt, Major Hale, bronze star with valor, word got around. Her hand had gone to her wrist without her noticing.

She felt the cool edge of the chain under the cuff of her sleeve. Outside in the hall, the clerk moved away quickly, shoes squeaking on linoleum. Marcus saw the motion of her hand and his eyes dropped to the fabric.

You still wearing it, he asked. She froze. Wearing what she asked.

He did not wait for permission. He reached across, gently took hold of her sleeve and lifted it just enough to see the dull flash of metal. The dog tag lay against her skin, the chain doubled, the stamped letters faded at the edges from rubbing.

That was Walker’s, he said quietly. Our medic. He used to fiddle with it when he was bored on convoy.

He had this nervous habit. Jordan pulled her arm back, tugging the sleeve down hard. He gave it to you the night before that patrol, Marcus continued.

Said if anything happened, you would make better use of it than he would. Her throat felt tight. Walker did not make it, she said.

No, Marcus agreed. He did not. But I did.

Because you were there. They stood in silence for a moment. On the TV, the anchor moved to a new story.

The caption at the bottom of the screen flipped to a different set of words. The break room door was not all the way closed. Out in the hall, low voices rose and fell, the pattern of gossip just getting started.

I came to say thank you, Marcus said. I have two kids now. I coach a terrible soccer team.

I still hate running, but I can do it if they make me. None of that exists without you. You do not owe me anything, Jordan said.

He smiled small and incredulous. That is where you are wrong, ma’am. Do not call me that, she said.

Not here. He considered that, then nodded once. Dr. Hale, he said.

Fine. But they should know who they are working with. Her eyes flashed to the doorway.

They do not need to know, she said. It is not relevant. Is that what you tell yourself? He asked.

She pushed her chair back. The legs scraped against the tile, breaking the fragile quiet. I have the patience, she said.

Marcus straightened. For a moment, he looked like he might argue. Then he stepped back instead, boots making a dull thud on the floor.

He lifted his hand, fingers pressed together, palm facing forward. It was not the casual half salute of a joke. It was precise.

Major Hale, he said. It is good to see you alive. She did not return the gesture.

Her hand stayed at her sides. Do not do that, she said. He held the salute a heartbeat longer, then let it drop.

The clerk who had passed earlier reappeared at the end of the hall with a friend in tow. They both slowed as they moved past the open break room door, eyes flicking to the uniform to Jordan, to the photo left on the table. Marcus gathered the picture and slid it back into the folder.

I will be around a few days, he said. They are making me sit through some reintegration thing at the base, if you change your mind about coffee. She did not answer.

He dipped his head once, almost like a bow, and left. The door swung shut behind him. Jordan stood alone in the sudden stillness.

The smell of old coffee seemed stronger now, her heartbeat in her throat instead of her chest. Outside in the hall, a nurse whispered. Did you hear him call her, Major? And someone else replied.

I thought she was just some quiet attending. Jordan picked up her cup with a hand that shook only slightly. The dog tag lay warm against her skin under the cotton.

The distant thrum of rotor blades reached down through the ceiling again, patient and steady. She set the untouched protein bar back in her locker a few minutes later, next to the Polaroid. This time she did not push the photo all the way into the corner.

She left a thin edge of it showing. Then she closed the metal door and went back out into the fluorescent light. By the next morning, the whispers had settled into the walls.

They were not loud. They were not meant for her. They rode the edges of conversations, tucked themselves into pauses, slipped out of half-open doors when she walked by.

Major, someone murmured near the medication room. Forward something team. Another answered near the charting computers.

She was supposed to be dead, a clerk said into a phone voice low, not as quiet as she thought. Jordan moved through it with her eyes on the monitors and her hands on charts. It felt like walking through steam.

Every now and then, a word condensed enough to sting. At the nurse station, a first-year pulled up an old military news article on his phone. The photo was grainy, blown up from something smaller, but it showed a row of dusty figures under a canvas awning.

A caption used words like valor and engagement. He turned the screen toward his friend, face bright with the thrill of discovery. Carla reached over and pushed the phone flat on the counter.

Work, she said. You both have patients. They flushed and scattered.

Jordan pretended she had not seen any of it. She clicked into labs, signed off orders, checked imaging. Her badge felt heavier than usual on its clip.

The chain around her wrist was a constant solid circle. In the locker room, she opened the metal door to grab a fresh scrub top. The Polaroid stared back at her, half visible, its white frame dingy at the edges.

For a moment, she considered pulling it off the inner wall again, hiding it. Instead, she changed quickly, shut the door, and let the thoughts sink under everything else. The day moved with an odd tension.

No single case was extraordinary. Chest pain, broken bones, a child with a fever that scared her mother more than it threatened the child. It was the way people watched her that was different.

Ethan deferred to her once or twice in small, quiet ways he had not before. He asked, You mind taking a look at this CT with me without layering a joke over it? Rick Halpern actually said please when he asked her to reassess someone who might need admission. By mid-afternoon, thunderheads were gathering over the city.

The light outside the high windows was a flat, hazy white. Inside the department, hummed. Jordan stood at the central desk, going over a stack of lab printouts when the overhead speakers crackled.

Attention all trauma personnel, the operator said. This is a mass casualty alert. Repeat mass casualty alert.

Highway collision involving a military convoy on I-35 near exit 12. Estimated eight critical patients, additional non-critical possible. ETA approximately six minutes.

The words took half a second to sink in. Then the room erupted. Chairs scraped.

People stood up all at once. Someone knocked a pen cup off the counter and did not bother to pick it up. The rapid shuffle of feet on tile layered with the sound of phones ringing and lines being picked up.

Get all trauma bays cleared, Ethan said, already moving toward trauma one. We will need three, maybe four, ready to go. Call or tell them we are sending at least two.

Rick had his phone pressed to his earbrow, furrowed. I am trying, he said. They are saying they are already full for the next two hours.

I told them that does not matter, but they keep putting me on hold. A resident nearly collided with the supply cart, mumbled an apology, and kept going. A tech began dragging portable vents out of storage, banging into door frames in his haste.

Nobody was looking at the big picture. They were all moving, all doing something, but the movement had no center. Jordan watched it all for a moment, the swirl of bodies and voices, the scattered commands that overlapped and left gaps.

She stepped away from the desk, into the open space between the nurse’s station and the trauma bays. Listen, she said. The word did not sound loud, but it carried.

Heads turned in her direction, almost on instinct. She did not wait. Ethan, you have trauma one, she said.

Focus, chest, airway, anything that cannot wait five minutes. Lynn, you are in trauma two, abdominal and pelvic, but you do not cut until I am in the room. Rick, you are triage.

You are the only one talking to EMS as they come in. Color coding on the board, no arguments with OR on this channel. Carla, you and two others are on blood.

Get O negative, hanging, and one and two have more in the fridge and a runner between here and the bank. Respiratory, get every vent you can to the trauma side and set them up before the first gurney hits the door. There was a heartbeat where no one moved the kind of stillness that comes after a dropped glass and before it shatters.

Then Ethan nodded. Got it, he said. Trauma one.

On it, Carla said, already moving toward the blood fridge. Rick lowered his phone and tapped the triage template on his tablet jaw setting. Okay, he muttered more to himself than anyone.

I can do that. The energy in the room shifted. It was still sharp, still urgent, but now it had edges instead of frayed ends.

Jordan walked into trauma two, then three, pulling curtains open, checking supplies with quick glances. Suction ready, intubation tray laid out, chest tube kits in reach. The familiarity of the checklist smoothed something rough in her chest.

The helicopter started up above a deeper thud that vibrated down the columns. The air vents rattled. For a split second, canvas walls flickered in the corner of her mind, but the fluorescent panels overhead stayed steady.

She pulled on a lead gown and gloves, then another pair of gloves over the first. The snap of latex and the rustle of fabric were a familiar rhythm. The doors from the ambulance base lit open with a mechanical sigh.

Heat rushed in along with the smell of exhaust and asphalt. The first gurney came through, pushed by two paramedics in sweat-soaked uniforms. A young man lay on it neck, immobilized face streaked with dust, a bloody dressing over his right chest.

Vehicle versus barrier, the medic called. Male, early 30s, possible tension, pneumo on the right, breath sounds decreased. Pressure 90 over 60, sats 85 on 15 liters.

Trauma 1, Jordan said, stepping aside. Needle him now, tube after. Ethan was already there.

He took the hand off without question. The second gurney rolled in almost on its wheels. A woman with her abdomen distended and a loop of bowel bulging through a tear in the skin.

Her skin was pale under the grime. Open abdomen unstable, the paramedic said. She has had two units.

Trauma 2, Jordan said. She is ours. Call or and tell them this is one of the ones.

The tech at the wall phone relayed the message voice, tight but clear. The third gurney carried a teenager with a leg missing below the knee. The stump was wrapped in stained bandages.

A tourniquet high on the thigh had a time written in marker on the skin. How long has that been on, Jordan asked. Three hours, the medic answered.

Yellow for now, she said. Get him into trauma 3, keep him warm, hang fluids wide open, but he can wait a little if we need the table. The hallway outside the bays began to fill with equipment and bodies, voices layered over one another, calling for more gauze, for drugs, for someone to hold a limb in place.

Rick stood near the doors, with his tablet eyes moving quickly from patient to patient as they came through, assigning colors and destinations. Two reds to OR already booked, he said into the phone. We need a third.

You can bump electives or you can explain to the general why his men died in the hallway. Jordan heard the edge in his voice and knew some part of him remembered her earlier directive not to argue on that channel. He was learning when to ignore it.

The fourth gurney came in slower. The man on it was older, maybe 50s, his face a ruin of swelling and blood. The sounds coming from his throat were raw and ragged.

Airway now, Jordan said. Quick tray kit. A nurse pressed the kit into her hand.

She palpated his neck in two swift motions, found the space she needed, made the cut, felt the tube slip into place. The gasping changed to a rougher, more regular sound. The monitor numbers steadied.

Secure it, she said, then moved on. The fifth ambulance crew nearly collided with a volunteer who had wandered too close. Out of the way, Carla snapped, pulling the volunteer back with a hand on her elbow.

You stay at the desk unless someone drags you. The fifth patient was lying very still, eyes half open, lips dry, a smear of blood at the corner of his mouth. His uniform was torn at the waist, the shirt cut away around a soaked abdominal dressing.

Male 20s, the paramedic said. Blast and rollover, penetrating trauma to the abdomen. We think there is internal bleeding.

His pressure has been soft the entire ride. Heart rate 130, sats low 90s on oxygen. He went quiet about 10 minutes ago.

Jordan put her hand on his belly. It was tight, swollen, the skin stretched shiny. Name, she asked.

Barrett, the medic said, Lieutenant Ryan Barrett, Army. Jordan felt the faint tremor of his muscles under her palm as another wave of pain rolled through him. His eyes tried to focus on the ceiling and failed.

We are not doing anything to him in the hall, she said, trauma. Two if we can squeeze him or straight to the elevator if there is an open room upstairs. Or says one suite just cleared the tech at the phone called.

They can take another in five minutes. Jordan met his eyes. Tell them this one is going up, she said.

And five minutes is too long. Trauma two, Jordan said. Move now.

The gurney wheels squealed as they pivoted. A nurse grabbed the IV pole, another took the head. They rolled fast, dodging carts and people in the hall.

Ryan’s eyes fluttered. His lips moved around a sound that never really formed. Lieutenant Barrett.

Jordan leaned over him as they pushed. You are at Alamo Heights. You got banged up on the highway.

We are going to take care of you. His gaze slid toward her unfocused, then away. In trauma two, the lights were already on full.

The bed waited bare. The air felt colder in there, the vents stronger. On my count, Jordan said, one, two, three.

They slid him across. The line on his monitor wobbled, then smoothed. His blood pressure numbers stayed low.

Cut the rest of his clothes, she said. I want everything off the abdomen. Scissors flashed.

Brown fabric fell away. Bruises bloomed along his ribs and across his hip, dark against pale skin. The dressing at his midline was soaked, deep red.

Hang another unit, Carla said. She squeezed the blood bag with both hands, forcing it down the line faster. Or wants to know if he is intubated yet, the tech at the doorway called.

He will be, Jordan said. Tell them we are on our way. She looked at anesthesia.

We are putting him down here. They nodded, already reaching for drugs. The smell of alcohol wipes hit the air.

Jordan put her palm back on his abdomen, feeling the tension, the heat. His hand twitched at his side. Lieutenant, she said.

You are going to go to sleep for a bit. You will not remember this part. His eyes blinked slowly.

His lips parted. Dad, he whispered. The word was barely there.

Jordan glanced at Carla. Has anyone called family yet? She asked. Military liaison is on it, Carla said.

If his dad is in the area, he is probably already on his way. Jordan stepped back to make space for the tube. The anesthesiologist slid plastic between Ryan’s teeth, guided the blade, watched the cords.

He is tube secure, they said a moment later. Good breath. Sounds both sides.

Wrap the dressing tighter, Jordan said. We do not want his guts on the elevator. They finished just as a commotion rose from the hallway.

Voices. A command tone cutting through the hum. The rhythm of boots on tile.

Jordan stepped to the edge of the curtain and pulled it back an inch. A man in dress uniform moved down the hall, flanked by two aides in blues. His jacket was dark, the silver stars at his shoulders catching every scrap of light.

His jaw was clenched. The lines at the corners of his mouth looked deep enough to hurt. Where is he? He said.

It was not a question so much as a demand pushed into the air. The charge nurse tried to keep pace with him, one hand up as if to slow him. General Barrett, sir.

We are still getting patients in. If you can wait in the family area, someone will update you. Where is my son? He said.

There was no room in the words for argument. Trauma too, Carla said behind Jordan. The general’s eyes snapped to the open curtain.

For a moment they went past Jordan without seeing her, and locked on the figure on the bed, pale under the monitors and tubing. He strode forward. The aides stopped at the threshold, knowing better than to push into the bay.

Ryan, he said. He stopped just short of the bed. His hand hovered over his son’s shoulder, fingers curling, not quite touching.

Ryan did not respond. The ventilator breathed for him, chest rising in quiet mechanical lifts. Jordan stepped between them without thanking her back to the general as she checked the dressings one last time.

Sir, I need space, she said. We are moving him. The room seemed to tighten further.

She felt the attention in the air, everyone waiting to see what would happen next. Who are you? The general asked. Dr. Hales, she said.

Trauma surgery. Who is in charge of this department? He asked. Jordan kept her gaze on the monitors.

Chief of emergency is Dr. Ward, she said. Chief of surgery is Dr. Monroe. I do not want chiefs, he said.

I want the surgeon who is taking my son to the operating room. Are you the most senior trauma surgeon here or not? His voice had sharpened. Years of barking orders had honed it to something that cut.

Jordan looked at him fully now. His eyes were the same shape as Ryan’s, just colder set deeper under the brow. He wore the tension of someone used to holding a thousand things together with willpower alone.

I am the attending, she said. He is my patient. His gaze swept over her.

Scrubs flattened hair, the faint ring of redness at her wrists from scrubbing. You ever seen anything like this outside of a textbook, he said. High-speed collision blast injuries, multiple casualties.

Yes, she said. Where, he asked. Kandahar, she said.

Fallujah, Mosul. The names landed one after the other. For a heartbeat, the hallway noise receded.

The general’s eyes narrowed. What unit, he asked. Forward surgical team attached to 5th Brigade, she answered.

Major Jordan Hale, Army Medical Corps. The silence in the bay deepened. A nurse stopped in the middle of taping an IV and just watched.

The general stared at her as if trying to peel back the years with his eyes. You are dead, he said quietly. No, she said.

I am busy. For a second, something like disbelief cracked his expression. Then it was gone.

Behind her, Ryan made a soft sound through the tube just air catching. His fingers twitched again. The general stepped closer to the bed.

His eyes softened around the edges as he looked at his son. Lieutenant, he said, voice lower now. Ryan, you hear me? Ryan’s eyelids fluttered.

Somewhere beneath the drugs and the pain, something registered. His right hand moved a fraction. It lifted off the sheet, hovering unsteadily.

Jordan saw it. The angle of the wrist, the way the fingers tried to close. Even intubated, half sedated, he was trying to salute.

It was clumsy, more a tremor than a gesture, but the intent was there. The general swallowed. The muscles in his jaw worked.

Save him, he said. Please. The last word sounded rusty, like it had not been used much.

I will do everything I can, Jordan said. That is not what I asked, he said. She held his gaze.

It is the only honest answer, she said. A beat passed. Then he straightened shoulders, squaring the general armor, sliding back into place over the father.

He took a half step back. Get him upstairs, he said. If anyone slows you down, you send them to me, Carla Jordan said.

Call transport. Tell them we are not waiting. We already have an elevator on hold, Carla replied.

They are clearing the path. They move fast. Monitors unhooked, then reattached to portable units.

IV lines checked again. The ventilator switched to a travel setting. The bed’s side rails clicked up.

On your left, a nurse called. As they pushed into the hall, warning everyone in their path. The general walked at the head of the group for three steps, then fell in beside them.

He kept his hand on the rail near Ryan’s shoulder, as if willing the bed forward. In the elevator, the walls were stainless steel. The fluorescent light overhead buzzed.

The space felt too small for the number of bodies inside. Jordan watched the numbers tick up. Her own reflection looked back at her from the polished metal.

For a moment, the mirrored image wore a helmet and a headlamp instead of a scrub cap. The doors opened to the surgical floor. The OR nurse waited outside mask hanging at her neck cap already on.

Room two is ready, she said. They rolled in. The air in the operating room was colder, sharper.

The overhead lights were huge white discs waiting. The anesthesiologist transferred Ryan to the narrow table. Monitors attached again cables like a nest of thin snakes.

Blood pressure 80 over 50, anesthesia said. Heart rate 130. Their gaze flicked to Jordan.

We do not have a lot of wiggle room. We will make it enough, Jordan said. She scrubbed in at the sink outside the room, water running over her fingers, the brush scraping gently across knuckles, nails, the backs of her hands.

The ritual steadied her. It always had. The OR door swung as people went in and out a series of brief glimpses.

Blue gowns, gloved hands, metal instruments laid out in perfect lines. Inside, she took her place at the table. Ethan stood opposite as first assist his eyes more serious than she had seen them in a long time.

You lead, he said. Good, she said. I was going to anyway.

The scrub nurse draped the field. A rectangle of exposed skin appeared marked already by bruises and dried blood, Knife Jordan said. The blade slid into her palm.

The handle felt familiar, the weight exactly what she expected. She opened the abdomen with one clean midline incision. The skin parted then, the fat, then the fascia.

The smell rose up a mix of blood and something deeper. Blood pooled in the cavity, dark and thick. It shimmered under the lights like oil.

Suction, she said. The tip of the suction wand hissed. Fluid disappeared, revealing loops of bowel, the curve of spleen, the underside of the liver.

There, she said. The spleen looked torn, a jagged rent in its surface. Blood welled from it steadily.

Near the hilum, an arterial branch spurted in thin, fast arcs. Clamp that she told Ethan. Gentle, do not crush it.

He obeyed hand steady. The liver had a slice along its edge, not quite through, but leaking. Smaller vessels oozed.

Pulseless with the clamp, anesthesia said. Pressure is up to 90 over 60, heart rate dropping into the 120s. Better, Jordan said.

We will keep going. She worked quickly. Her fingers found the splenic artery.

She tied it off, then packed the area with laparotomy pads. The bleeding slowed to a seep. She turned her attention to the liver, closing the laceration with a series of deep sutures, each one placed with care.

The tissue felt friable under the needle, but it held. At one point, the suction hose clogged with a clot. The scrub nurse cleared it without Jordan having to ask.

It felt like everyone was thinking half a step ahead together for once. She checked the intestines, ran her hands along them, feeling for other injuries. Nothing obvious.

No hidden tears or perforations. The peritoneal cavity was messy, but manageable. Check his pressures, she said.

105 over 70, anesthesia replied. Heart rate 110. He is holding.

Jordan exhaled slowly. She had not realized she had been holding her breath. All right, she said.

Let us close. Layer by layer, she brought the abdomen back together. Fascia, then subcutaneous tissue, then finally skin.

The last knot sat neatly at midline, a simple mark over the chaos beneath. She stripped off her top pair of gloves. The skin of her wrists was marked by faint indentations.

You did good work, anesthesia said quietly. Jordan nodded once, already half turned toward the door. In the hall outside, the general waited.

He stood alone this time, hat in one hand, the other in a fist at his side. The lines in his face looked deeper. Jordan pulled off her second pair of gloves, tossed them into a bin, and stepped toward him.

He is stable, she said. His spleen was ruptured. His liver was lacerated.

We controlled the bleeding. He will go to the ICU for monitoring. Barring complications, he should recover.

The general’s shoulders eased in a visible way. He let out a slow breath. Thank you, he said.

It was simple. No extra words loaded on. Jordan nodded.

He studied her for a moment. I read a report once, he said, about a convoy hit outside Mosul. The FST that covered them lost contact for 72 hours.

Intelligence reported the team destroyed. Later they amended it, killed in action. Major Jordan Hale listed among them.

I was not dead, she said. So I see, he said. His mouth tightened in something that was almost a smile and almost a grimace.

Seems the Army’s loss is this hospital’s gain. He adjusted his grip on his hat. I thought you were gone, he said.

A lot of us did. I left, she said. That is different.

He nodded slowly. My son called you ma’am, he said. Even drugged.

That means something in my line of work. There was a memory there for him that she did not reach for. He is a good officer, she said.

He is a good kid, the general replied. The word slipped out before he could catch it. He did not correct himself.

They stood in silence a few seconds longer. Nurses and orderlies moved around them wheeling carts, hurrying to and from other rooms. The hospital kept moving.

I will be in the ICU, he said finally. If there is any change, we will let you know, she said. He gave her a short nod, not quite the formal thing from the hallway downstairs, but not casual either.

Then he turned and walked toward the elevator’s uniform, straight back rigid. Jordan watched him go until the doors closed. She turned back toward the sink, washed her hands again, even though there was little left to rinse away.

The water ran clear over her skin. Above her, the faint beat of helicopter blades carried through the building. She listened for a second, then dried her hands and headed down the corridor toward the stairwell that would take her back to the emergency department.

The ICU was quieter than the emergency department, but the quiet did not feel like rest. It felt like something holding its breath. Jordan stood at the foot of Ryan Barrett’s bed, watching the monitor trace its green line.

The numbers beside it were not perfect, but they were steady enough. The ventilator sighed in and out, lifting his chest in small, regular movements. He looked younger, without all the dried blood and torn fabric.

Just another kid in a hospital bed, hair mashed against the pillow face, slack with sedation. She checked his incision, dressing the drains, the lines. Everything was where it was supposed to be.

Anything you want changed, the ICU nurse asked from the doorway. Keep his pressures where they are, Jordan said. Watch his urine output, call me if it drops.

If he spikes a fever, draw blood cultures right away. Got it, the nurse said. Family is in the lounge.

I know, Jordan said. She stepped out of the room. The door closed with a soft click behind her ceiling and the steady beeping.

The family lounge was down the hall, a rectangle of beige chairs and old magazines, a vending machine humming in one corner. The coffee in here was worse than downstairs. General Barrett stood near the window, not sitting, not pacing just there.

His hat rested on the plastic side table beside him. Outside the sky over San Antonio had turned a heavy gray the first drops of rain streaking the glass. He heard her footsteps and turned.

How is he, he asked. Stable, she said. He tolerated the surgery as well as we could ask.

The first 24 hours are the most important for watching his blood pressure, his kidneys, any signs of re-bleeding or infection. If he gets through those clean, his odds go way up. He nodded slowly, absorbing each piece.

He will not be waking up tonight, she added. Anesthesia will keep him sedated for a while to give his body a chance to catch up. Fine, he said.

He has done enough for one day. There was an attempt at humor there, faint and strained. It did not quite make it to his eyes.

They stood facing each other with the soft rattle of the vending machine between them. You have children, he asked. No, she said.

Good, he replied after a beat. You do not need this particular kind of panic. He said it dryly, but his hand flexed once at his side.

Jordan shifted her weight. You said something earlier, he went on, about Mosul. I have been trying to decide if I imagined that part.

You did not, she said. He picked up his hat, turned it in his hands, then set it down again. In 2017, he said a convoy out of the old city lost contact.

We had sporadic reports, bad comms, dust storms. Command could not get a straight answer. For three days, the status on the forward surgical team was unknown.

He spoke like someone reciting a report he had read too many times. When we finally got a clear line, he continued, the position was gone. The tent was shredded.

The vehicles were burned. Bodies everywhere. The first estimates said the entire team had been wiped out.

Medical security, everyone. Later, when we managed to count, they still did not find you. He looked directly at her.

They listed you as killed in action anyway, he said. Administrative closure. Move on to the next line item.

I did not die, Jordan said. They were wrong. What happened, he asked.

She drew a breath. The ICU air smelled like disinfectant and recycled oxygen, but under it, she could suddenly taste dust again. The city was a mess, she said.

Streets choked with rubble wires hanging buildings half down. We were set up in a courtyard that used to be a school. The convoys brought the wounded straight in.

Some on stretchers, some carried. We did what we could. Her voice flattened without her intending it.

That day, we took 12 casualties in about 30 minutes, she said. All critical. We had two surgeons, one anesthesiologist, four nurses, a couple of medics who had not slept in two days.

Barrett listened without interrupting. The only sound came from the television in the corner, turned down so low that the voices were just a murmur. I was working on a lance.

Corporal Jordan went on. Shrapnel to the abdomen. We had his bowel out.

We’re patching holes, trying to close. He was young, maybe 22. Freckles.

Kept joking about how he had finally gotten out of gate duty. Her hand found her wrist again, thumb grazing the line of the chain under her sleeve. A squad leader came in behind him, she said.

Traumatic amputation at the hip. Bright red blood arterial everywhere. He was awake and talking and losing his entire volume right in front of us.

Her eyes were not on the lounge anymore. She saw canvas walls and dirt, the flicker of lanterns, the way shadows had danced on the tent ceiling. The anesthesiologist looked at me, she said.

The other surgeon was already tied up with someone who had a chest full of metal. There was no one else. It was either let the squad leader bleed out while I finished the abdominal closure or leave the Lance Corporal with a nurse and move.

Her jaw clenched. I told the nurse to keep pressure on the belly, she said. I said I would be right back.

I went to the squad leader. We clamped his vessels. We packed the wound.

We got him to a stable point. Her voice had dropped. The rain outside started to tap harder against the glass.

When I went back, she said the Lance Corporal was gray. There was more blood on the floor than should have been there. The nurse was doing compressions and calling my name.

His eyes were open, but they did not see anything. She stopped. Her throat worked once.

She forced the rest of the words out. Ten feet away, she said. I was ten feet away, and he died while I was holding someone else’s artery shut.

Barrett’s grip on his hat tightened. The knuckles whitened. Before I opened his abdomen, she said he asked me if his mother would be proud of him.

I told him yes. I told him she would be very proud. Her eyes burned.

He died thinking that she said. He died while I was somewhere else. And we kept going because there were still more stretchers coming through the flap, and the mortars were still landing close enough to make the instruments jump.

Silence settled between them. The only sound from the hallway was the distant squeak of a cartwheel. How many did you save that day? Barrett asked quietly.

She frowned. That is not the point, she said. How many, he repeated.

She looked away. Eleven, she said. We lost one in the tent and a couple more before they could be evacuated.

So call it nine. Maybe ten. It depends how you count.

You saved eleven, he said. You lost one. You made the choice you had to make.

I chose who lived and who died, she said. I am the one who pointed and said you, not you. I heard the nurse call my name, and I did not come fast enough.

Nobody could have saved them all, he said. I was supposed to try, she replied. Her voice cracked on the last word.

She hated how much that bothered her. You did, he said. From what I hear, you tried harder and longer than anyone had a right to expect.

She shook her head. You went back after Mosul, he said, to another assignment. For a while, she answered.

Then I stopped sleeping. I could hear mortar blasts in the air conditioning. Every time I scrubbed in, I saw his face.

I saw the others. I could not walk into the tent without wondering who I was about to fail next. And so you left, he said.

So I left, she said. He nodded once, the motion small. The record says you vanished, he said.

No forwarding information. No clear transfer. Just gone.

Some of us thought you could not take it. Some of us thought you had earned the right not to. She let the words hang.

You did not disappear because you were weak, Dr. Hale, he said. You disappeared because you had been carrying bodies for too long on your own. I came here to be just a doctor, she said.

Not someone’s war story. Not someone’s legend. Just the person who shows up for their shift and does their job.

You are that, he said. And you are the other thing, too, whether you like it or not. She looked at him.

The rain slid down the window behind him in thin, crooked lines. I do not want them treating me differently because of something I did in another life, she said. They already are, he said.

The difference is now they know why they instinctively look at you when things start to fall apart. His voice softened a fraction. Do not hide from that, he said.

She did not answer. He picked up his hat again and settled it under his arm. I need to get back to my son, he said.

He is going to wake up confused and irritated and he will feel better if there is a familiar face somewhere in the blur. Jordan inclined her head. As his surgeon, I am obligated to tell you not to get in the way of the nurses, she said.

I would not dare, he replied. He walked past her toward the ICU doors. As he reached them, he paused.

One more thing he said without turning. You saved 15 of mine in Kandahar, and now you have saved my son. That is not a debt I can pay back, but I will say it plainly.

I am glad you are not dead. He pushed the door open and went inside. Jordan stayed in the lounge until the tightness in her chest eased enough that she could breathe without thinking about it.

On the way back down to the emergency department, she stopped in the stairwell. The concrete walls were cool. The hum of the building felt different here, muffled and distant.

She took the stairs slowly, one hand on the rail. At the landing between floors, she heard the faint chop of rotor blades as a helicopter lifted off the pad above. The vibration ran through the metal under her palm.

For once, it did not pull her backward. It just sat there, a physical reminder of where she was. The emergency department looked different when she stepped back in, though nothing had changed.

The same battered chairs. The same whiteboard full of names and room numbers. The same smell of coffee and bleach.

People glanced up when she passed. A couple of residents straightened unconsciously. Rick’s eyes flicked to her, then away quickly.

Dr. Hale, the unit clerk, called. Dr. Monroe asked if you could go up to his office when you have a moment. Jordan’s shoulders tensed.

Now, the clerk added, he said, preferably now. All right, Jordan said. She took the elevator to the fourth floor.

The surgical administration suite had carpet instead of tile, and the walls were painted a softer color that tried to suggest calm. It did not entirely succeed. Dr. Elias Monroe’s office was at the end of the hall.

The door was open. He sat behind a wide desk, reading glasses low on his nose, a stack of charts to his left. His hair had gone almost entirely white, but his eyes were sharp.

Behind him, a large window showed the hospital courtyard and the city beyond the storm clouds, layered like bruises over the skyline. Come in, Dr. Hale, he said. She stepped inside.

Close the door, please, he added. She did. Sit, he said, gesturing to the chair across from him.

She sat. He removed his glasses and set them on the desk, folding one arm over the other. I have been going through numbers, he said.

It is something I do when I cannot sleep, which lately is most nights. Jordan waited. You have been at Alamo Heights for 18 months, he said.

In that time, you have taken on more high-acuity cases than any other trauma attending. Your complication rate is the lowest in the group. Your response times from page to bedside are consistently under three minutes.

He tapped the folder in front of him. Patients mention you by name in satisfaction surveys, he went on. They mention calm, clear explanations, feeling safe.

A few cannot spell your name to save their lives, but I know who they mean. OK, she said cautiously, and yet he continued. You have let residents send you to do sutures, as if you were their intern.

You have taken consults nobody wanted. You have stayed late to help others close without putting your name anywhere near the case. You have been in a word invisible.

I prefer to focus on the work, she said. So do I, he replied, which is why we are having this conversation. He opened another folder.

Inside was a printout with a grainy photograph she recognized. The caption mentioned a forward surgical team and a convoy attack. I did not know about this, he said.

About your prior service record? That is on me. I should have read more closely when you were hired. The CV said trauma experience in theater.

It did not mention that the theater was Mosul under mortar fire. It was not relevant, she said. He raised an eyebrow.

You do not think it is relevant that one of my attendings has more real-time mass casualty experience than the rest of my department combined, he asked. You do not think it is relevant that you have made life or death triage decisions in circumstances the rest of us only see in symposium slides. She shifted in her chair.

I came here to be a doctor, she said, not a symbol. You are both, he said. Sitting in that bay today, you organized a chaotic trauma response with fewer words than most people use to order lunch.

People listened. Not because of rumors or newspaper clippings, but because you knew what needed to be done and said it in a way that cut through the noise. He leaned forward.

I want to offer you a position, he said. Director of a new trauma leadership program. You would design the curriculum for trauma fellows, oversee their training, set the standard for how we teach decision-making under pressure.

You would have the authority to restructure how we respond to events like the one today. The words hung in the air between them. Jordan stared at him.

Why me, she asked. Because you know what matters when everything goes sideways, he said. You know the difference between what we like to think we will do and what actually happens when there are more patience than hands.

We can teach technique. We are less good at teaching mentality. You have both.

She looked past him at the window. Beyond the glass rain fell in a study sheet now. The city lights were beginning to come on in scattered points.

I do not want to be in front of anything, she said. I do not want a title that changes the way people talk to me. They are already talking differently, he said.

You can either let them build their own story around half-facts and rumors, or you can step into a role where your experience actually shapes something useful. He sat back. I’m not asking for an answer tonight, he said.

Think about it. Talk to whoever you need to talk to, but do not take too long. These chances do not sit still forever.

She opened her mouth, then closed it. Dr. Hale, he said more softly. You left one war zone.

You are in another, even if the uniforms look different. The difference is here you get some say in how the next generation goes into it. Do not throw that away because you are tired of people saluting you.

She let out a breath she had not meant to give away. I will think about it, she said. Good, he said.

He picked up his glasses again. That is all I ask. She stood knotted once and left the office.

In the stairwell, the concrete felt cool against her shoulder when she leaned there for a moment. The echo of her own footsteps followed her down as she descended. Back in the locker room, she opened her locker and took out the Polaroid.

She held it in her hand longer this time, tracing each face with her thumb. Dusty uniforms, tired eyes, crooked smiles. Walker standing off to one side, dog tag glinting at his throat.

She taped the photo back to the inside of the door, higher where it sat at eye level. It was not fully exposed, but it was no longer hiding in the shadowed corner. The chain at her wrist pressed warm against her skin when she closed the locker and stepped back under the humming fluorescent lights.

The conference room on the third floor smelled like dry erase markers and coffee that had cooled an hour ago. Fluorescent lights buzzed overhead, softer than in the emergency department, but still too bright. Twenty residents sat in tiered rows, some with laptops open, some with notebooks and pens poised.

A couple of them glanced at their phones and then thought better of it. Jordan stood at the front with a remote in her hand. The screen behind her glowed blue waiting.

She cleared her throat once. Morning, she said. Asin.

A scattering of morning Dr. Hale came back at her uneven. I was asked to give this week’s trauma conference, she said. You usually get case reviews, protocol updates, things like that.

She clicked the remote. The blue shifted to an image. A canvas tent under a bleached sky, its sides flapping slightly in a wind you could almost feel.

Sandbags around the base. Two stretchers in front occupied. A figure in scrubs bent over one of them.

This was my operating room for two years, she said. The room went quiet. Someone shifted in their chair the sound loud in the stillness.

No CT scanner, she said. No angiosuite. No backup on call if something went wrong.

We had what we brought in on the planes and what we could improvise from whatever was lying around. She clicked again. The next slide showed a close shot of a gloved hand inside a chest cavity, fingers curled around a bleeding vessel.

The skin around the incision was stained a deep brown-red. I learned a lot there, she said. Not because the injuries were worse than what you see here.

Some were, some were not. I learned because there was no space for ego, no time for hesitation. If your hands froze, people died.

She let that sit a moment, then moved to the next slide. A simple diagram of a torso. Landmarks for needle decompression, for chest tubes, for emergent thoracotomy.

We are going to talk about decisions under pressure, she said. Not in the abstract. In the time it takes to walk from the ambulance bay to trauma one.

She worked through a case. A young man with multiple fragment wounds, hypotensive, altered. She asked them to call out priorities.

Airway breathing circulation, which they would sacrifice, which they would accept as imperfect, for a moment. Hands began to rise more readily as the cases went on. Residents argued politely over whether to intubate before placing a chest tube, whether to run to the CT scanner or call the operating room from the bedside.

At one point, a first year in the second row frowned and raised her hand. Dr. Hale, she said. How do you stay calm when you walk into a room and everybody else is already panicking? Jordan looked at her.

You do not start calm, she said. You choose what to pay attention to. A few pens paused over paper.

You walk in and you find the things that matter, she continued. Is the chest rising? Is the neck vein full? Is there a puddle under the bed? You talk in full sentences. You keep your voice level.

People match you whether they mean to or not. What about the other stuff? The resident asked. The noise, the family screaming, the monitor alarms.

You let somebody else handle what they can, Jordan said. And you accept that you cannot control all of it. A third year near the back lifted his hand.

How do you deal with the ones you lose? He asked. Afterward, the room shifted. Chairs creaked.

No one looked at anyone else. Jordan’s fingers tightened on the remote for a second. You remember them, she said.

You remember what went wrong if anything did. You write it down. You talk about it with somebody who understands the medicine, not just the feeling.

You carry it so you do not make the same mistake twice. Her throat felt dry. She took a sip of water from the paper cup on the podium.

Losing someone does not mean you failed, she said. But it does mean you have to show up fully for the next one anyway. She moved the slide forward again, back into anatomy, and numbered steps.

The rest of the hour passed in a mix of questions and diagrams and clipped descriptions. When she finally clicked to the last slide, the one that simply said, Questions in plain black font. Nobody spoke for a few seconds.

Then hands went up again. Practical things this time. Dosages.

Timing. Whether it was better to open a chest in the bay or wait for the operating room. She answered each one as precisely as she could.

When it ended, the residents did not rush out. Some stayed filing down the rows to the front. Thank you, the first year, said the one who had asked about staying calm.

This was different. Differently terrifying, her friend added with a crooked smile. Jordan nodded.

You will see versions of all of it, she said. Sometimes in the same hour. They drifted away at last, leaving half-finished coffee cups and the faint smell of warmed plastic from the projector.

She was packing up her notes when she realized someone was still in the doorway. Ethan leaned against the frame arms folded, watching her. How much of that did you hear, she asked.

Last 15 minutes, he said. I was late. They had me on a call with administration about bed flow.

He stepped into the room, letting the door swing shut behind him. That was a good talk, he said. I have been sitting in these conferences for years.

I do not remember the last time anyone said out loud that people die even when we do everything right. It is not a secret, she said. We act like it is, he replied.

He moved closer hands now in his pockets. I owe you an apology, he said. She stared at him.

For what she asked. For acting like I was the only one in the room who knew what they were doing, he said. For taking credit when you were the one who saw the bruise that mattered or called the bleed before the scan.

For treating you like backup instead of like the person I should probably be listening to. His tone was even. It did not feel like a performance.

You did your job, she said. I did part of it, he said. You did the other part and then some.

He rubbed his jaw. When Marcus came in, he said. And called you major in the break room.

I thought it was some weird mix up. Then I heard your name in the trauma bay with that general. Then I saw you open that kid’s chest like it was muscle memory.

It took me an embarrassing amount of time to add it all up. It does not change the work, she said. It changes what I think when you tell me I’m taking too long, he replied.

His mouth quirked, but his eyes stayed serious. I am not good at this part, by the way, in case that was not clear. But I am trying.

She let out a breath. Some of the tightness behind her ribs loosened. Apology accepted, she said.

He nodded once. If you ever want someone to bounce ideas off for this leadership program, Monroe is dreaming up, he said. I would like to be in the room.

For the record, he offered, she said. I know, Ethan said. He came by the department looking for you before he paged.

He also swore me to secrecy, which I am breaking in a very small way right now. She said nothing. I will get out of your way, he said after a moment.

You probably have three people waiting to page you about things they should solve themselves. He left with a small lift of his hand and something like a farewell. Later that afternoon, back in the emergency department, the crowd at the nurse station parted a little as Jordan walked up to check labs.

The whispers had changed texture. Less speculation, more watching. Dr. Hale, the clerk said, holding out a folded note.

A man dropped this off for you, said his name is O’Neill. The paper smelled faintly of takeout. Inside, in a strong, slightly cramped hand, was a single line.

Coffee, if you ever decide you deserve something that does not taste like battery acid, I will be by the front entrance at 1700. Marcus had underlined the time. She put the note in her pocket and went back to work.

The day wore on. Chest pain ruled out. A kid with a broken wrist.

A woman with a headache that turned out to be a slow bleed. Each case took a piece of her attention. None took all of it.

At five minutes past five, she stepped outside through the main entrance. The air had cooled after the rain. It smelled of wet pavement and cut grass from a strip of lawn between the sidewalk and the parking lot.

Cars moved in slow lines at the drop-off lane. Marcus sat on a low wall near the door, a paper tray with two coffees beside him. He stood when he saw her.

I was about to give your cup to the security guard, he said. Sorry, she said. Trauma consult.

Would have been a waste, he said. He drinks that vending machine sludge like it is holy. She picked up one of the cups.

It was heavier than the ones from the staff room. The cardboard sleeve was printed with the name of a local place, not the hospital logo. You did not owe me this either, she said.

Let us pretend I did, he said. It makes it easier for me to carry. They sat in silence for a few sips.

The coffee was strong and sharp, but it tasted clean. It warmed her from the inside without making her stomach flip. How is the leg, she asked.

He grinned. Sometimes it forgets we are not in the desert anymore, he said. Likes to ache when it rains.

But it works. Ran a 5K with my daughter last month. She beat me.

Has not stopped talking about it. You let her win, Jordan said. Do not tell her that, he replied.

He studied her profile for a moment. You going to take it, he asked. Take what she said.

The program, he said. The thing with teaching. Saw something on the bulletin board downstairs about a trauma fellowship getting restructured.

Monroe’s name, your name in small print under it. They do not usually add names for fun. I have not decided, she said.