The rank on my shoulders—the gleaming, silver eagle of a U.S. Air Force Colonel—has always felt lighter than the constant, crushing weight of motherhood.

I am Colonel Riley Thompson. To the world, the media, and my subordinates, I am a woman who commands a wing of advanced reconnaissance aircraft. I deal with classified intelligence, high-stakes geopolitical maneuvering, and decisions that can shift the course of national security. I have flown sorties over hostile terrain where the radar lock warning was the only music playing. I have sat in rooms with Joint Chiefs and discussed the acceptable margins of error in drone warfare. But my greatest fear, the one thing that keeps me awake when the base goes quiet and the flight line lights dim, isn’t a foreign adversary or a compromised server.

It is a tiny, invisible metabolic imbalance in a school lunchroom.

My daughter, Ella, is eight years old. She is brilliant, kind, and terrifyingly fragile. She was born with a rare, severe metabolic condition—Medium-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency, or MCADD, complicated by severe reactivity to processed additives. It’s not an allergy. It’s not a “dietary preference” or a lifestyle choice. It is a non-negotiable biological reality.

If her blood sugar drops below a certain threshold, or if she consumes ingredients her body cannot process, she doesn’t just get a stomach ache or a rash. Her body loses the ability to convert fat into energy. She goes into hypoketotic hypoglycemia. She seizes. Her organs start to shut down.

Food, for Ella, is a prescription. It is a life-support system, just as vital as an oxygen tank would be to a diver.

We had followed every single protocol. I was a military officer; I lived and died by protocol. I had provided the school—the highly-rated, prestigious “Northwood Elementary” in the suburbs of Virginia—with binders full of physician’s notes, legal waivers, and emergency action plans. We had meetings. Oh, God, we had so many meetings.

I sat in tiny chairs across from the principal, Mr. Collins, and the school nurse, Mrs. Turner. I explained the science. I showed them the charts. They nodded. They smiled that tight, polite smile civilians give when they think a mother is being “overprotective.” But they signed.

The school had signed the federally mandated Individualized Healthcare Plan (IHP). It was a legal contract. A promise that they would keep my little girl safe while I served my country.

They knew the special, insulated silver lunchbox was not a choice. It contained precise macros: MCT oil, specific proteins, zero processed sugars. It was medicine in the form of food.

Yet, every single month, there was a new petty battle. A substitute teacher questioning her snacks. A lunch monitor making a snide comment about her “fancy” food. I had fought them all down with emails and phone calls.

But today? Today went beyond petty. Today was an act of war.

The morning had started like any other. I was up at 0400. I did my PT, running five miles around the base perimeter while the mist was still clinging to the hangars. By 0600, I was in the kitchen, weighing Ella’s chicken and asparagus on a digital scale that measured to the tenth of a gram. I packed it into the thermal-regulated container. I locked the lid.

“Mommy, do I have to go?” Ella had asked, rubbing sleep from her eyes. She looked so small in her oversized pajamas.

“You do, bug,” I said, kissing her forehead. “You have math today. You love math.”

“Mrs. Bennett doesn’t like my lunch,” she whispered. “She says it smells weird.”

“Mrs. Bennett doesn’t have to eat it,” I said, smoothing her hair. “And if she says anything, you tell her to check the binder. Okay?”

“Okay,” she sighed.

I dropped her off at the circle. I watched her walk in, her pink backpack bouncing against her spine. I had a bad feeling in my gut—an instinct honed by years of combat zones. But I had a mission. I had a briefing with the General. I drove away, forcing myself to trust the system.

I was wrong.

The call came at 11:47 AM.

I was in the middle of a high-level briefing in the Secure Compartmented Information Facility (SCIF). The room was windowless, soundproofed, and cold. It was lit only by the blue glow of tactical maps projected onto the wall, showing satellite positioning over the Pacific.

My personal phone, which is strictly for emergency family use during these hours and usually locked in a signal-proof box, was in my pocket today. Ella had had a low fever the night before, and I had broken protocol to keep it on me. It buzzed against the mahogany table.

Unknown number.

Rejected.

Buzz again.

I answered under the table.

“This is Colonel Thompson.”

It was Chloe, Ella’s best friend. Whispering. Scared.

“Colonel Thompson? It’s Chloe… Mrs. Bennett did something bad. Ella is crying. She’s shaking really bad. She’s holding her tummy. She’s not eating. Mrs. Bennett took it. She threw it in the garbage. She said Ella didn’t need to eat today.”

The line cut.

My world stopped.

I stood up so fast my chair slammed backward.

General Whitaker stared at me, confused.

I hit the secure line.

“Sgt. Major Briggs. Two-man detail. Full dress. NOW. Rendezvous point: Northwood Elementary. Code Red-Seven.”

He didn’t ask questions.

I grabbed my cover.

General Whitaker asked, “Is everything alright?”

“No, Sir,” I said. “But it’s about to be corrected.”

I sprinted out of the SCIF.

The drive to Northwood Elementary was a blur of asphalt and fury.

Corporal Davis drove with the calculated aggression of a man used to navigating convoys through hostile urban centers. We were doing eighty in a forty-five zone. The SUV’s grill lights flashed—red and blue strobes reflecting off the manicured lawns and white picket fences of the suburbs.

I sat in the back, staring at the digital watch on my wrist. 11:58 AM.

Ella had last eaten at 06:30 AM. Her snack break was supposed to be at 10:00 AM. If Mrs. Bennett had confiscated that too, Ella’s glycogen stores were already depleted. We were entering the danger zone.

“ETA two minutes, Colonel,” Davis announced.

“Step on it,” I murmured.

Beside me, Sgt. Major Briggs remained silent. He was checking his gear. He wasn’t armed with a service weapon—we couldn’t bring firearms into a school zone without a federal warrant or an active shooter situation—but he didn’t need a gun. He was six-foot-five of solid muscle, trained in hand-to-hand combat and intimidation tactics.

We screeched into the school parking lot, bypassing the line of SUVs waiting for kindergarten pickup. Davis jumped the curb, parking the government vehicle diagonally across two “Faculty of the Month” spots.

Parents dropped their keys. A janitor froze mid-sweep.

We hit the double glass doors of the main entrance.

The security buzzer system—a flimsy plastic box with a camera—was the first obstacle. I didn’t wait to be buzzed in. I flashed my military ID against the glass and pounded on the door with the flat of my hand.

The secretary, Mrs. Higgins, stood up so fast her chair rolled back. She saw the uniforms. She saw the fury. She hit the buzzer instantly.

The lock clicked. We were in.

“Colonel Thompson?” she stammered. “You… you need to sign the visitor log. You need a badge.”

“I am not a visitor, Mrs. Higgins,” I said without slowing. “I am a first responder to a medical emergency caused by your staff. If you attempt to impede a federal investigation, Sgt. Major Briggs will detain you for obstruction.”

She sat down.

We pushed through the inner doors.

The hallway was peaceful, colorful, childlike. A lie.

“Davis, hold the rear. Nobody follows us,” I ordered.

“Yes, Ma’am.”

Briggs and Lewis stayed at my sides. We marched down the hallway, boots pounding a steady, ominous rhythm.

Room 302.

Closed door. Voices inside.

“…and that is why we follow rules, class. Because when we don’t, we create distractions. Ella, sit up. Stop being dramatic.”

My pulse spiked.

I didn’t knock.

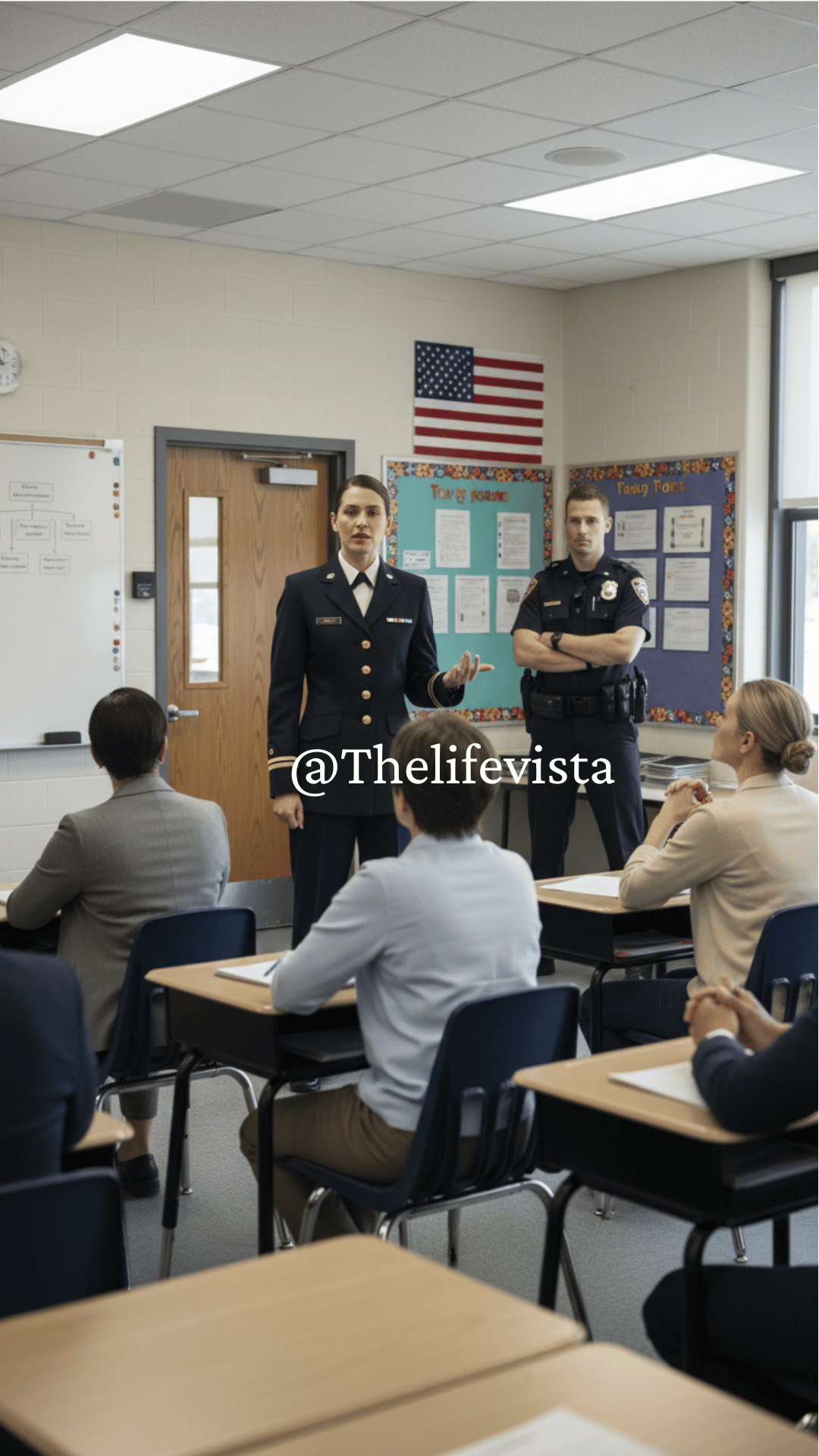

I slammed the door open.

The room froze.

Twenty-two fourth graders turned. Mrs. Bennett stood mid-lecture, marker in hand, face draining of color.

“Colonel Thompson?” she hissed. “You cannot just enter my—”

I ignored her.

I scanned the room for my daughter.

There. Back row. Alone.

Ella sat hunched over, forehead on the desk, trembling. Her skin was pale. Lips blue-tinged. Eyes glassy and unfocused.

She was crashing.

I crossed the room in three strides.

“Ella,” I whispered, my voice cracking. “Baby, look at Mom.”

She lifted her head slowly. “Mommy… I feel… floaty.”

Hypoglycemia.

I tore open a glucose gel pack with my teeth.

“Open up.”

She obeyed weakly. Swallowed.

I checked her pulse. Too fast. Too thin.

“Miller!”

(But in this version: “Briggs!”)

“Ma’am!”

“Medical kit. Now.”

Briggs was beside me instantly, setting a trauma kit on the desk.

That was when Mrs. Bennett found her voice again.

“This is unacceptable! You are frightening the children! Ella is fine. She’s pretending because I took her lunch away. She needs to learn she isn’t special just because her mother wears a costume.”

The room went dead silent.

Briggs froze in place.

I stood.

I am five-seven. She was taller. But in that moment, I looked down on her.

“A costume?”

My voice was lethal calm.

“Where is it?”

“W–where is what?” she stuttered.

“The lunchbox. The silver medical container. Where. Is. It.”

Her eyes flicked to the trash can.

I followed her gaze.

I walked to the can. Looked inside.

There it was.

On top of used tissues. Pencil shavings. A rotting banana peel.

Chicken smeared with garbage. Asparagus coated in dust. Lid dented.

She hadn’t just confiscated it.

She had destroyed it.

“You didn’t just take it,” I said, trembling. “You threw away my daughter’s medical treatment.”

“I… I was making a point,” Mrs. Bennett whispered. “I told her, ‘You’re not special.’”

“Sergeant Major,” I said without looking away from the trash.

“Colonel.”

“Photograph this. Then bag it as evidence.”

Click. Flash. Click.

“You can’t do that!” Mrs. Bennett shrieked.

“This,” I said, holding the evidence bag up to the light, “is no longer a classroom. It is a crime scene. And you are the suspect.”

At that moment, the door burst open.

Principal Collins, panting, sweating. “Colonel Thompson! What is happening here?”

I turned. Held up the bag.

“Your teacher,” I said, “just tried to kill my daughter.”

“Kill? That is… that is preposterous,” Principal Collins stammered, wiping sweat from his receding hairline. He looked from the evidence bag in my hand to the terrified teacher, and then to the hulking form of Sgt. Major Briggs. “Colonel, I understand you are upset, but let’s not resort to hyperbole.”

“Hyperbole?” I stepped closer to him. The sound of my boots on the linoleum was the only sound in the room.

“Mr. Collins, do you know what hypoglycemia does to a child with MCADD?” I asked, my voice terrifyingly calm. “It’s not just hunger. It’s metabolic failure. Her brain stops getting fuel. She has seizures. She slips into a coma. And if not treated immediately, she dies.”

I pointed to Ella, still slumped at her desk as the medic worked on her.

“If I hadn’t walked in here at 12:00 PM, she would have been unconscious by 12:15 PM. Mrs. Bennett threw away her medicine. That is not hyperbole. That is cause and effect.”

Collins puffed up his chest, trying to regain ground. “Mrs. Bennett made a judgment call regarding classroom policy. Perhaps it was misguided. But bringing military police into a public school? This is an overreach of jurisdiction.”

He turned to Briggs. “Sir, I must ask you and your men to wait outside. You are frightening the students.”

Briggs didn’t blink. Didn’t move.

“He doesn’t move until I order him to,” I said. “And right now, he is securing a scene where a federal crime has occurred.”

“Federal crime?” Collins scoffed. “This is a lunchroom dispute!”

“It is a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act,” I snapped. “And because Northwood Elementary accepts federal funding, you are bound by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.”

I unzipped Ella’s backpack, pulled out a bright red binder, and slammed it onto Mrs. Bennett’s desk.

“Page one: ‘Medical Necessity of Dietary Accommodations.’ Page three: ‘Prohibition of food confiscation under any circumstances.’ Page five: YOUR signature, Mrs. Bennett. Right next to mine.”

She stared at it.

“You signed a document stating you understood that taking her food could kill her.”

I leaned close.

“And you did it anyway because the container wasn’t transparent enough for your rules?”

She shook.

Then the hallway erupted.

Parents.

Teachers.

Reporters.

Rumor had spread like wildfire: Colonel Thompson is at the school with MPs.

They pushed against the door window, trying to see.

Collins panicked. “Colonel, please, let’s go to my office—”

“You can go wherever you want,” I said. “I’m calling JAG.”

I dialed.

“I am calling the Superintendent!” he countered, grabbing the classroom phone.

“You do that.”

My medic spoke up. “Colonel—the child’s sugar is climbing. She needs food ASAP.”

“Copy.”

Just then—sirens.

Two Sheriff’s deputies entered, led by Deputy Rodriguez, who drilled at my base as a reservist.

“What’s going on?” Rodriguez asked.

“Child endangerment,” I said. “Evidence bagged. Witnesses present.”

He turned to Mrs. Bennett.

“Ma’am, did you throw this child’s lunch away?”

“I was enforcing rules!” she cried. “I didn’t know she’d get sick!”

“Did you know about her condition?”

“I—well—I signed something, but I have thirty students! I can’t remember every little diet!”

“It’s not a diet,” I said. “It’s a disability.”

Rodriguez sighed and closed his notebook. “Mr. Collins, she needs to leave campus pending investigation.”

“You can’t be serious!” Collins gasped.

“I can,” Rodriguez replied. “And I am.”

Mrs. Bennett burst into tears as they escorted her out.

Principal Collins followed, pale, shaking, realizing his career was collapsing right there in Room 302.

And then came the walk through the hallway.

Sgt. Major Briggs leading.

Deputies behind him with Mrs. Bennett.

Then Collins, sweating.

Then me, carrying Ella, her arms weak around my neck.

Parents stared. Some gasped. Some filmed.

When we stepped outside into the bright sun, Ella whispered:

“Is it over, Mommy?”

“The bad part is over,” I told her. “We’re getting burgers.”

I buckled her into the SUV.

“Orders, Colonel?” Briggs asked.

“Diner on Main,” I said. “And Briggs?”

“Ma’am?”

“You did good today.”

He nodded once.

But farther down the street… a teenager pulled out her phone. Uploaded a video secretly filmed under her desk.

By the time I took the first bite of my cheeseburger…

…it had 3.5 million views.

And the entire country now knew the name Mrs. Bennett.

We sat in a booth at Louie’s Diner, a retro spot with red vinyl seats and a jukebox that played Elvis. It was a world away from the sterile, terrifying silence of Room 302.

Ella was halfway through a cheeseburger. Every bite she took made my chest loosen. Color was returning to her cheeks. Her eyes were bright again.

Sgt. Major Briggs and Corporal Jensen sat at the counter, black coffees in hand, still in quiet sentinel mode. Watching every door. Calculating threat vectors. They didn’t know how to turn it off—neither did I.

My phone buzzed.

Then again.

Then continuously, vibrating like an angry hornet against the table.

I ignored it. Ella mattered more than any notification in the world.

“Mommy, your phone is dancing,” she giggled.

“It can dance,” I said softly. “Eat your fries.”

But Briggs stood, looking at his own phone.

“Colonel,” he said slowly, “you… may want to see this.”

I frowned.

“What did you do, Briggs?”

“Nothing, Ma’am. But one of the students did.”

He turned the screen toward me.

A TikTok video.

Caption:

“Teacher tries to starve girl, gets OWNED by Air Force Mom. #JusticeForElla”

I clicked.

The screen showed the shaky angle of a camera hidden under a desk.

“You don’t need to eat,” Mrs. Bennett’s voice sneered.

“You can wait until your mother brings you something more normal.”

Then the door SLAMMED open.

There I was, storming in like a missile.

“Mrs. Bennett, you have violated a federal IHP… This is no longer a school. This is a CRIME SCENE.”

The comment section was a firestorm:

“As a diabetic… this made me bawl. That teacher should NEVER work again.”

“The MP just STANDING THERE like a final boss.”

“Colonel Thompson for PRESIDENT.”

“Damn right, protect that baby!”

3.5 million views.

Posted two hours ago.

“Oh, God,” I whispered.

“Colonel,” Briggs said, checking updates, “it’s everywhere. News stations. Twitter. Parents are throwing metal lunchboxes on Mrs. Bennett’s lawn.”

My phone rang.

General Whitaker.

I answered. “Sir—”

“Ava,” he said, voice grave but amused, “I just got off a call with the Pentagon’s press office.”

“Sir, I didn’t authorize—”

“Relax. You defended your family. The Air Force stands with you. JAG is taking over the legal fallout. You take care of Ella.”

“Yes, Sir.”

“And Ava?”

“Yes?”

“Next time you deploy a security detail to an elementary school—give me a heads up so I can pop popcorn.”

I hung up.

Briggs smirked.

“Civilians hate bullies, Ma’am. And today? You nuked one.”

THE FALLOUT

It was immediate.

Principal Collins resigned within 48 hours.

Mrs. Bennett lawyered up—but the evidence was airtight. The school board meeting had to be moved to a high school gymnasium because hundreds of parents, veterans, and reporters stormed the original venue.

People held signs:

“FOOD IS MEDICINE.”

“DON’T MESS WITH COLONEL THOMPSON.”

“PROTECT OUR KIDS.”

I spoke once.

“My daughter fights a metabolic war every day. She shouldn’t have to fight her teacher too.”

Silence. Then an explosion of applause.

The board voted unanimously to terminate Mrs. Bennett.

Her license was revoked by the state.

She pled out to child endangerment. A misdemeanor. Community service. Her career: gone. Her reputation: obliterated.

But the victory came later—

The district adopted the “Ella Thompson Protocol.”

Mandatory medical-plan briefings for every staff member. Food for medically fragile kids classified as medical devices. Zero tolerance for confiscation.

EPILOGUE

Three weeks later, I drove Ella to school for the first day back.

She gripped a new lunchbox—purple, her favorite.

“Mommy? Will Mrs. Bennett be there?”

“No, baby. She’s gone. Forever.”

“Who’s my new teacher?”

“Mr. Davis,” I said. “Retired Army medic. He knows all about your food. Says your MCT oil is ‘pretty awesome.’”

She giggled.

I watched her walk to the doors—small, but standing tall.

I sat with the engine running and breathed.

I had jets to command. Pilots to train. Satellite intel to review. A whole wing depending on me.

But none of that—not medals, not rank, not operations—will ever matter like she does.

I am Colonel Riley Thompson.

I command the skies.

But down here, boots on the ground, fighting for one little girl with a fragile metabolism—

I am just Mom.

And that is the highest rank I will ever hold.