When James Sullivan arrived from England—Margaret Collins’s nephew, restless with an inheritance and a curiosity for plants—he did not see Cotton as an ornament. He saw her in the garden, fingers index-fine through indigo leaves, inhaling the scent of wet earth. He asked, simply, “Do you know indigo?”

Cotton blinked at him because questions from white men carried currents. A mistake could cost more than a beating; it could cost sale and separation. “I saw it in Barbados,” she said. “We had fields once. The people there, they worked different soil. You must lime, and drain, and plant with air between the rows.” She said it as if listing steps in a recipe—careful, flat, without a flare that might invite attention.

Where planters saw a curiosity, James saw opportunity. Indigo had been England’s color and colonists’ dream. It had faltered in Georgia; cotton and rice had taken its place. But if the right soil and care could be coaxed into producing the deep blue the market demanded, the profits would stack like casks in a warehouse. Cotton’s knowledge felt to him like a map out of years of poor harvests.

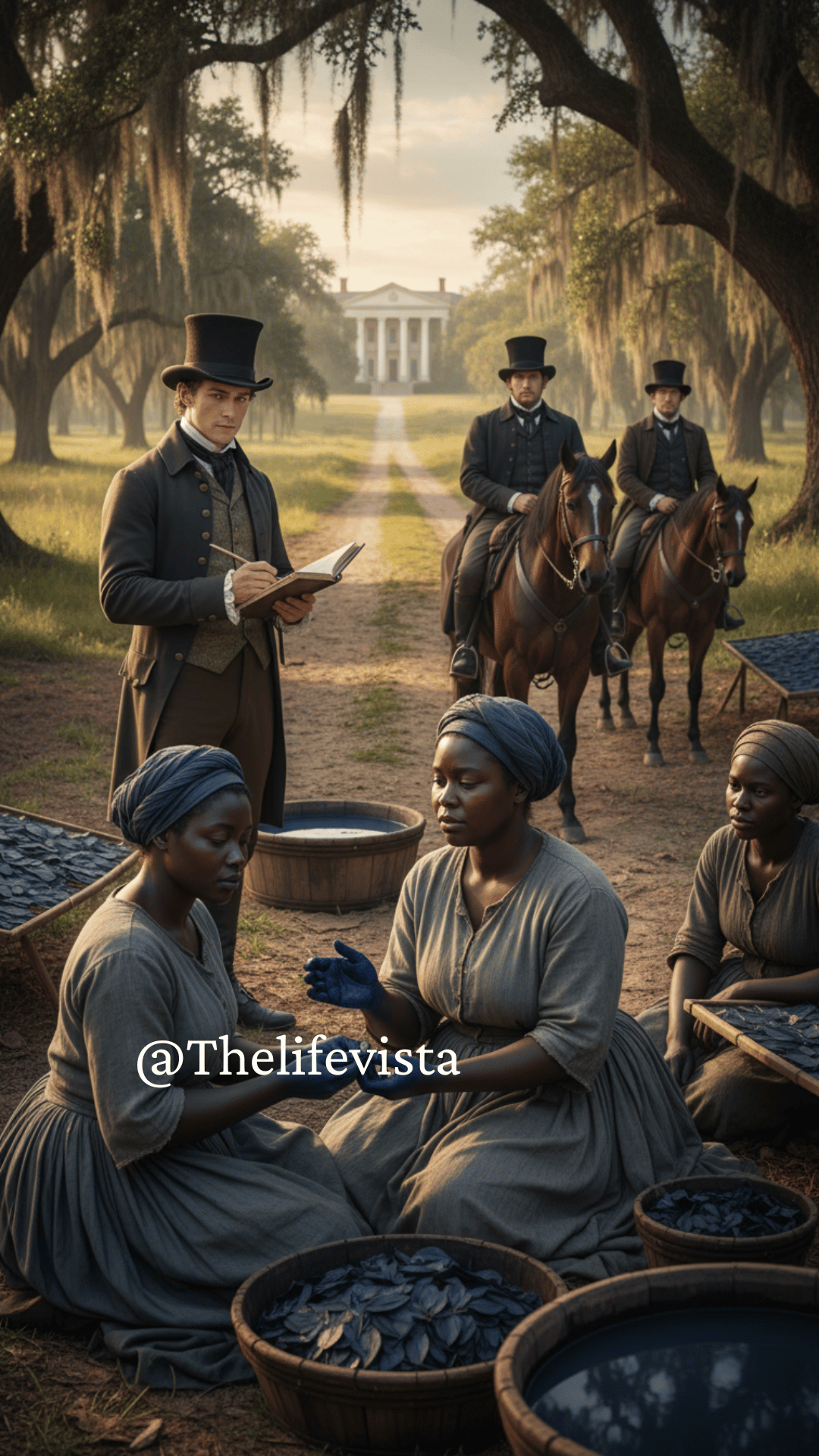

They arranged an experiment on James’s forty-seven acres. Cotton taught. She showed Samuel Carter, a field worker loaned for the season, how to soak stalks and judge a pulp’s smell; she showed Patience Johnson, a woman who had worked for years and who would, later, become the most dangerous keeper of secrets, how to fold leaves and press them until the dye came clean. James wrote everything down as if converting memory to a ledger might somehow sanctify it. For the first time in a life conditioned to make herself small, Cotton had leverage: knowledge that could be given, that could be diluted into ordinary hands and therefore diluted in value. It was a bargain she would come to orchestrate.

News traveled in the rural towns of Georgia like a cough. Rumor drew Vincent Monroe, who had failed at other schemes and saw in Cotton what any desperate man sees—an asset to be commanded. He offered two thousand dollars for her, which was an obscene sum for a woman whose life was already measured in account books. He wanted not only the person but the secret she harbored. Dr. Nathaniel Crowe wanted to examine her as a specimen for his paper about hereditary traits. Both represented the same thing: to be desirable was to be sold again and again, to become an object of study and an engine for other men’s profit.

When Monroe came swaggering with legal papers—inked witnesses, dated transfers—he brought the law to bear like a blade. He claimed Calder Wells had sold Cotton to him years before, a claim that, on paper, outranked Margaret’s informal sale. The magistrate, uncomfortable and pressed by signatures and notary seals, ruled that Monroe could take her until the court in Savannah could hear the fuller case. Cotton heard the words as if from a place far away. She understood ownership as a loop in which she had always been the object.

She surprised them all. When Monroe’s men advanced, she looked him in the eye and said, voice quiet and clear, “I won’t work for you.”

He laughed at the insolence of a woman who had no legal voice. “You’ll do what you’re told,” he said.

“You can own me, but you can’t own what I won’t give you.” Her refusal was not fury; it was a calculation. Monroe misread it for obstinacy and ordered her seized.

What happened next was not heroics and not a plan written in the minutiae of revolution. It was the chaotic, frightening arithmetic of people who had nothing left to lose. Samuel and Patience and four others who had learned Cotton’s methods looked at one another, and in their eyes she read a decision that did not require her consent. They caused a distraction that was simple and noisy: a spilled tub, shouts of fire, tools clattering. While the men set about calming the storm, Cotton slipped into the tobacco-drying house at the field’s edge. She hid there for four days, fed covertly by Patience through a seam in the shutter.

The magistrate allowed a search until nightfall and then, embarrassed by his own authority, stopped. The court in Savannah accepted Margaret’s lawyer’s challenge to the forged papers. Monroe’s claim fell away when handwriting could not be matched and wax seals proved anachronistic. Margaret kept Cotton, but the threat had revealed something ugly and true: knowledge made a person a prize.

Cotton could have tried to be newly valuable—reticent, private, and rare. Instead she proposed the opposite, a barter that weaponized unremarkability. She would teach the craft to three people—James, Patience, and Samuel—and in return demanded protections written into her title: she could not be sold out of Georgia, could not be forced into field labor, could not be subjected to medical examination without consent. In the language of property those were constraints; in the language of survival they were lifelines.

The plan worked better than she might have dared hope. Over nine days she taught until the measure of a good dye was as familiar to two rough palms as to her own. James wrote fast; his notes would become a manual for a revived crop. The court ruled in Margaret’s favor and, for the moment, the thing Cotton guarded became less precious because it was shared.

That was the first of her many bargains. She meant to make herself uninteresting in the marketplace. She knew the calculus of desire: rarity inflates price, value attracts extraction. If the same knowledge lived in the hands of many, if her body could be rendered ordinary, the hands that reached for her would have less reason to make cruel offers. She planned for survival like others planned for harvest: put the seed deep, tend it quietly, make the roots strong.

Years unspooled with the slow, indifferent rhythm of sales. Margaret died. Cotton was sold to a Charleston merchant and then to a string of houses; the price went up and down, sometimes for display, sometimes for need. In every new home she practiced the same art—polish the cups until they shone and speak only when spoken to, smile enough to be amiable and never so much to be remarkable. She kept her head down and gave away only what ensured her continued safety. She learned the names of children and the times their mothers preferred tea. She learned how to keep a room’s temperature even when her own knees ached.

The second lesson came later, and it was not planned. Vincent Monroe’s death—recorded as an accident—was not an accident at all. Thirty years after the court decision, when Cotton was settled into Richmond under the care of a practical boarding-house keeper named Martha Keane, a letter arrived, delivered by a merchant who did not know its freight. It was from Patience Johnson. She wrote with a hand that had learned shapes in secret classes she’d paid for with stolen minutes: “I am dying,” it began. “I must tell you this before I go.”

Patience wrote of the wet November afternoon when the wagon axle snapped, when the wheel crashed into the river and Monroe was trapped beneath. She wrote of Samuel and four others and of how they had weakened that axle in the smithy days before. They had watched him drown. “We could have helped,” Patience wrote, “but we did not. We could have called on someone to save him, but then he would have come for you and for the knowledge. We did it so you might live.”

Cotton held the letter by the thin light of her room and the world tilted under her feet. Her plan for being unremarkable had never included murder. She had made choices—careful ones—about distribution and safety. But someone else had chosen for them. She had been kept alive by a decision she had not made. The knowledge she had taught in good faith had been guarded with blood.

She burned Patience’s confession. The fire ate the shaky handwriting and left only the smell of smoke and the heavy weight of knowing. It was not confession for her to carry; it was a secret wrapped in guilt and gratitude and a complicity she did not remember consenting to. Cotton cried then in the dark for the man who had died, for the hands that had taken it upon themselves to end him, and for the brutal logic of survival that lay at the heart of what they had done.

The letter’s revelation did not change the ledger’s entries. Cotton continued to be sold and resold, her price slowly plummeting as age stole the vigor buyers wanted. Men who had once dreamed of profit no longer cared; she had become a household manager, then an orderly for the boarding house, then a seamstress in the quarter for the free black community when the war tilled the landscape into chaos and abandoned the things it had once treasured.

Cotton’s life was lived in the thin margins of motion and memory. She made bargains: one with James that had turned indigo into cash and taught a handful the techniques that would make their labor worth more than the sums they were paid; one with herself to remain forgettable; one with the world to preserve what little control she could have in a place that considered her nothing but property. She practiced a small, sharp kind of diplomacy—divide the secret, limit the sale, keep the knowledge accessible enough to be useful and common enough to be worthless.

When Dr. Nathaniel Crowe turned up, years later, with a notebook and the bland mission of science, she faced him as she had faced Monroe—reserved, uncooperative. He wanted specimen and study and perhaps fame; she wanted to remain anonymous and whole. “If you write of me,” she told him once in the dim of a boarding house garden, “I will say I never worked with indigo. I will say it does not exist.” He smiled, as if dismissing a child’s bluff, but the meeting left him without the access he sought. He wrote a paper anyway, more about curiosity than proof, and filed it where scholars file curiosities: under “unverified.”

There were joys and small mercies. People in the free black community in Richmond gave her a place to sleep and food in winter. A young teacher named David Harper—nervous, earnest, with a pencil that chewed paper—came to her when she was in her eighties. “They say you remember,” he said, and his eyes were wide with the hunger of a man who wanted to think he might preserve a life’s truth for posterity.

She told him what she could. Harper took notes and prodded with a gentleness Cotton found almost absurd. He asked about prices and owners and the feeling of the indigo leaves between fingers. He asked whether she regretted making herself unremarkable. Cotton thought so long that the old woman’s face furrowed like the soil she had once coaxed to yield dye. “I survived,” she said finally. “That is not nothing.”

Harper left her with a promise to preserve her words, and for a while that promise felt like a thin wreath. It did little to unwrap the harder truths she carried: Patience’s tremulous admission, the face of Vincent Monroe under water, the quiet hours when she had sat and tried to name what part of her was strategy and what part was surrender. Was survival a victory if it required the death of another? Was unremarkability a triumph if it depended on someone else’s blood? She had no tidy philosophy. She had a long, practical ledger of choices, of how to move when the market said one thing and the soul pressured another.

The Civil War unspooled the old order by violence and neglect. Catherine Wells fled her Richmond home with only portable goods, leaving Cotton and two other elderly people behind. For the first time in a lifetime spent under contracts, leases, and sells, Cotton found herself unowned in practice if not by law. She lived then like a ghost in a house that had no master, an old seamstress in a city of many ruins. When the Union marched in and the records of ownership collapsed amid fires and ruined deeds, Cotton found herself truly free—an emancipation delivered late and without fanfare, a legal status arrived when her knees could no longer carry more than a basket of linens.

She tied up her life’s seams with small tasks. She sewed for the neighborhood, patched shirts for soldiers and quilts for nursing mothers. The money she earned was not much, but it bought coffee sometimes and a warm bed. She visited a church where the preacher spoke of forgiveness and resurrection and felt in his words the strange looseness of a horror and relief stitched together. On a winter morning she would sometimes stand in the doorway and watch children run, their laughter catching like bright cloth on a line. She thought of Patience and Samuel and the others who had watched a man drown. She thought of the guilt that had made Patience confess on a page, and of the way confessions burned and left only ash.

When David Harper returned decades later, his notebook fat with interviews of many elders, she allowed him to ask the questions about indigo, about sales, about the strange ledger of white hair written in different hands across thirty-six years. Her answers were spare. She told him of Barbados in a voice that made the sea sound near and of the patience of field hands who knew the crops like bones. She told him, finally, of strategy more than of specifics. “Once,” she said, “I decided the most valuable thing I had was not my body but what I knew. People will pay for either, but I could give knowledge away and be harder to buy.”

Harper wrote her words into the paper of a city that would forget the drama of small lives amid larger histories. It would not be until later—much later—that historians would find James Sullivan’s notes in a drawer, medical quirks in a chest of an old college, the shaky handwriting of a dying woman hidden under a merchant’s seal. The fragments would sit in separate rooms, unstitched.

Cotton lived long enough to see the ledger’s numbers dwindle to nearly nothing. Men who had once seen a profit now no longer cared to buy what age had made less useful. She was hard to sell because she was old and arthritic and because the clauses that had been written into her title—those limits that James had convinced Margaret to accept—traveled with her, making her less saleable. Those clauses that had saved her from prurient study and from forced labor also lowered her market price. They protected her by putting a cap on her desirability.

She died, in the end, as many old things do: small, unnoticed by the ledger keepers and loved by a few. A black doctor named Thomas Freeman saw her through a fever and signed what little paper was asked for in the city’s blunt bureaucracy. They buried her in a yard for people like her, in a plot that time later paved over, a grave lost to the city’s appetite for buildings and parking lots. A dozen people sang and laid down a hymn and the coffin was lowered. No marble would bear her name.

But there are other kinds of records. David Harper’s notes remained folded in his papers, and James Sullivan’s indigo logs stayed in the back of a drawer, a recipe for blue ink on a page. In time, different people found these things in different places—an archivist here, a graduate student there—and they started to ask questions that led them, in pieces, to one life. None of the fragments said the whole, and the whole was messy and moral in ways archives are not good at measuring. The evidence that the system’s very premise was false—evidence that African minds had knowledge worth money, skill, and memory—was scattered, unnoticed, treated as curiosity.

People asked, too late, whether Cotton’s strategy had been a success. There is no universal metric for what it means to live through. She survived nine sales, and that single fact sits heavy in its own language. She was not a heroine in the public sense, not a figure who led others into open revolt or whose portrait hung in a city gallery. What she did was smaller in scale and sharper in ethics: she made herself less interesting, less profitable, and therefore safer. She traded latent value for years of life. She accepted the slow erosion of outward dignity in exchange for the possibility of care.

If anyone reading her story asks whether she won, or whether she lost, they will find themselves answering according to what they value. Cotton survived long enough to see slavery collapse and to sit under a government that finally, belatedly, acknowledged rights she had fought for in small ways. She carried a secret that she had not asked for and kept it like a jewel she refused to sell. She did not choose the violence done in her name, but she lived under its protection and its shame.

In the end, Cotton—whatever her true name had been—left a life that was both testament and puzzle. She proved, to anyone who would read the scattered notations of ledgers and letters, that black minds had learned, taught, and preserved knowledge that planters and doctors had tried to monopolize. She proved that choices made to survive could be about cunning and calculation rather than only brute force. She proved, in the smallest of ways, that the system that enslaved her was built on a lie.

Her story—told in the tone of a seamstress and the precision of an indigo hand—reminds those who read it that many lives are saved not by thunderous acts but by quiet negotiations. She had wanted to be unremarkable; in that she succeeded. And in being unremarkable she taught a lesson no ledger could tally: survival is a kind of craft, and to practice it well sometimes requires paying a price that cannot be calculated in dollars.