Won $8M Lottery – Guard Your Son Put Pills in Your Coffee!

I won the ticket on an ordinary Saturday the way ordinary miracles often arrive—soft, ridiculous, and disguised as habit. For twenty years I’d stopped at the same 7-Eleven on Morrison Street, same fluorescent hum, same cashier who pretended not to know my name. Helen used to laugh and call it my Sunday superstition. “Daniel,” she’d say, drying dishes while I stood in my socked feet scratching a corner of the world away, “one day you’ll win big and ruin us.”

We both laughed. She died before I could find out whether she was right.

When the phone on that Saturday buzzed in my hand, the voice on the other end was flat and businesslike—the lottery official confirming what my tired eyes already told me. I’d scratched the dollars off with a nail I’d bitten down to the quick: 7, 14, 23, 31, 42, Powerball 9. Then I called the number the receipt advised and listened as a clerk asked me to come in. With a pension and forty-three years of construction in my bones, I’d expected the lump sum discussions to be polite and small. Instead they were dizzying: lawyers, accountants, a financial adviser who sounded as if he’d swallowed a spreadsheet.

After taxes, the number that settled into my account was $8.5 million. It was a clean, surgical thing—enough to make mistakes with, enough to fix some of the crooked things life had left in my yard. It felt, at first, like breathing for the first time in years.

My daughter Anna shrieked when I told her. She’d always been my soft place—practical, loving, a nurse practitioner now living in Seattle with a family I had built alongside Helen. She promised trips, renovations, and said, between tears, that I should finally do the things Helen had always wanted: travel, fix the roof she’d nagged me about, plant a proper rose garden.

Jason called later. He’d always called in a different voice, the one that smelled of the world beyond our doorstep—cars, deals, always sales. He’d been a sensitive boy once, an artist who spent afternoons making paper mâché landscapes; life had ground the edges off him until art felt like a pastime for other people. Now he was forty-five, in a lease BMW, in a house knotted with debts, and married to Vanessa, a woman whose laugh measured profit margins. Jason was excited. He wanted to celebrate. He wanted, politely and warmly, to shepherd me into projects I’d never asked for.

I told him yes to dinner—because family, because Helen would have expected me to try—and because maybe I’d missed something in a son I had watched change like weather. I said yes, and then the months folded themselves into a story that began with a cup of coffee in a hospital cafeteria and nearly ended with something worse.

County General was the sort of place I’d known intimately in small, pragmatic ways. I’d been going for quarterly checkups for my blood pressure, for a doctor who liked to ask about my home projects and called me Daniel with warm, professional fondness. Jason rang, fortuitously near the time of my appointment. “I’ll be right there,” he said. Two weeks later he and Vanessa swept in like wind, full of plans and smiles. We ate sandwiches and talked about things they wanted me to invest in: a downtown commercial building, a boat, a family business. I listened to their pitch once, twice, thrice. I said no. I had a financial adviser, and I liked to think I knew better than to mix family with investment.

Vanessa excused herself to the restroom and returned with two green hospital mugs; they were the sort of thing you expected in a place like County General—cheap, chip on the rim, anonymous. She placed them on the table like an offering. “Let’s not fight,” she said. “Family first.” But her fingers brushed across mine in a way that left an echo.

Then my phone rang. Three minutes for a call that felt important. I stood in the corridor for better reception and listened to the adviser explain trust documents and disbursements. When I came back, Jason was reaching across the table, and I bumped his arm as I sat. The coffee sloshed. The chipped mug slid and landed on his side. I didn’t move it back. Small gestures can be dangerous things.

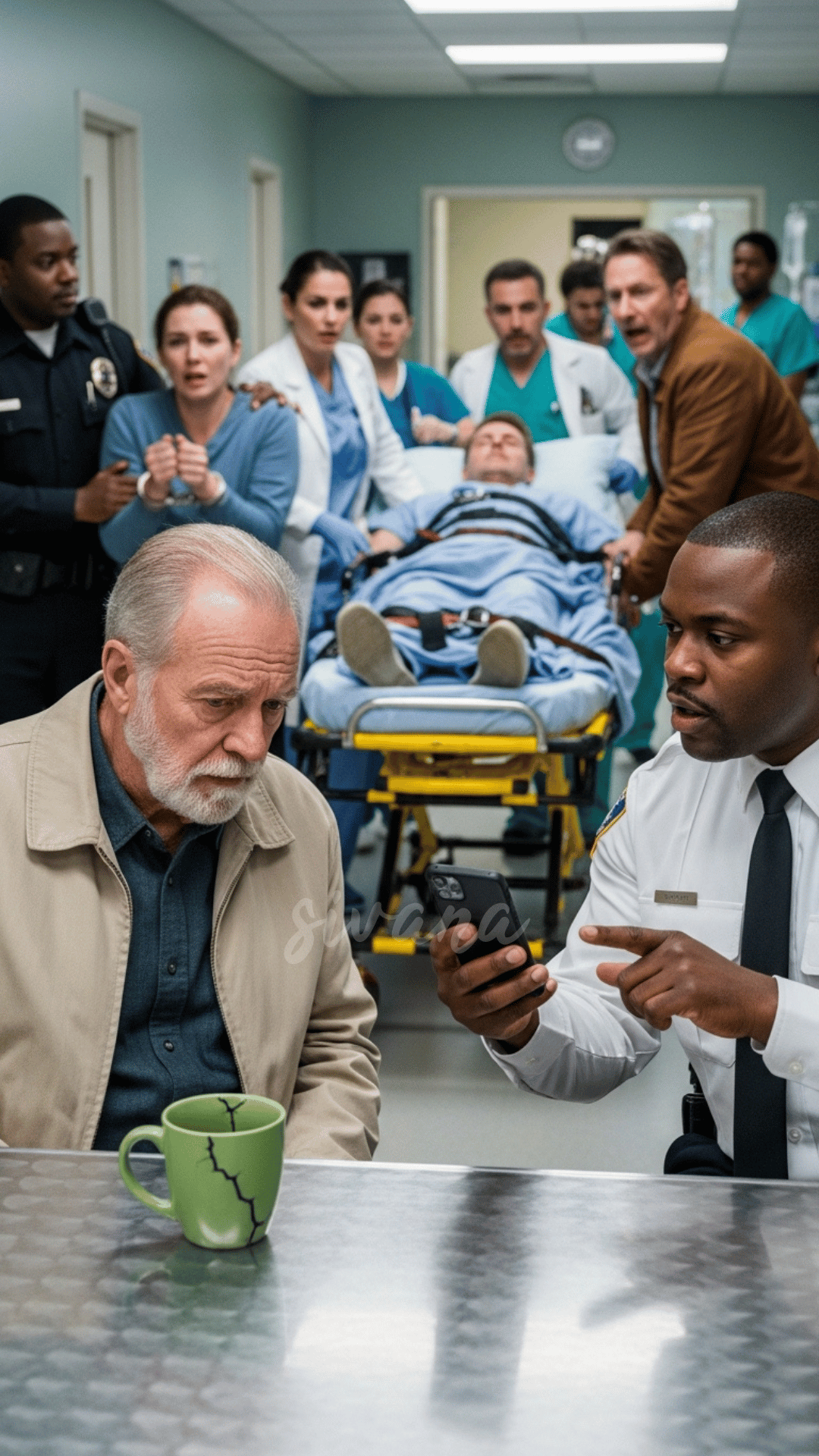

We talked a little longer. They pushed again. I refused again. Jason picked up the chipped mug and drank. Ten minutes later, his face collapsed inward. “I don’t feel good,” he said, like someone reading a paragraph of their life that didn’t make sense. It was easy, at first, to accept benign explanations: forgot to eat, low blood sugar. But his hands began to shake, his pupils were wide, and sweat dotted his temple. I shouted for a nurse. The staff descended with a clarity I had always associated with battlefield triage and construction sites: quick, ordered. Jason began seizing. The cups were bagged as evidence.

While Jason fought for the air, a man named Robert—a hospital security guard who’d shared a cigarette with me once on a winter night while we waited for a friend—approached and asked to speak privately. He had footage .. He’d seen Vanessa pull a small plastic bag from her purse, Jason pour powder into the chipped mug, and then, in the brief concussion of my phone call and the spill, the cups had been swapped. Robert had hesitated to go to the police because he’d thought perhaps he’d misread the scene; that’s what ordinary good people do, hesitate before making mountains of accusation. But the camera did not lie.

I felt the world tilt. Not only because my son had tried to poison me, but because the idea that he had looked at me and seen dollar signs instead of the man who had changed his diaper and taught him to swing a hammer. Vanessa was gone when I looked for her, but I found her at the exit, mascara streaked, voice gone thin as she tried to explain that it wasn’t supposed to be Jason; it was supposed to be me. “Just enough to make you disoriented,” she said, collapsing to the floor as if the weight of their plan had finally found its spine. “So you’d sign. We have a power of attorney. We’re drowning, Daniel. We can’t keep the house.”

Hearing her say that—so blunt, so small—I felt every possible betrayal like sediment settling in my chest. The police arrived, the tests came back. The pills were a benzodiazepine, Rohypnol mixed with sedatives—enough to incapacitate, not enough to kill, unless someone like me, with blood pressure and an old heart, took it. The pharmacist record, the security footage, a forged signature and a notary stamp purchased online: each piece of evidence fit together like a guilty puzzle. They arrested both of them.

The weeks that followed were not the sort that make for good conversation. They were heavy with legalese and empty chairs, with abasement and the strange awkwardness of a family broken by greed. The DA asked if I would press charges. I said yes. I had to. There was a principle here beyond my personal devastation: you did not try to end your father’s life because you wanted a better kitchen. You did not teach your boy to hold a pill bottle and then look at his father like an ATM. If I wanted Jason back in any real sense—if I wanted him to learn and atone—there had to be consequences.

At the trial, the defense tried the old, tarnished angles: she coerced him, she manipulated him, he acted out of love and desperation. But desperation is not an excuse for betrayal. The jury saw the footage. They saw the journal Vanessa kept, the meticulous list of steps and dates, the materials needed, the power of attorney drafted with both their fingerprints on it. Jason’s handwriting in the margins did not look like a passive annotation. The judge called it a betrayal of the most fundamental trust known. The jury agreed. Jason was sentenced to four years. Vanessa received six.

I sat in the courtroom and tried to catalog the emotions because if I didn’t name them they would become a shapeless, dangerous thing. Anger. Shock. A sense of being unwound. But among them, and maybe the smallest, there was also sorrow. There was sorrow for the boy who once drew bluebirds with a careful hand on the margins of schoolbooks, who had once kissed his mother’s forehead and promised to look after us. There was sorrow that greed had rewired a man I had raised.

Outside the court, Robert found me. He had been there in the cafeteria that day with eyes that did not like to look away from trouble. He was nonchalant and embarrassed about his heroism, but I was not. “You saved my life,” I told him. He shrugged, humbly. “Doing my job, sir.” I insisted. I set up a small fund for his daughters’ education, paid off his mortgage, wired enough to let him breathe. He closed his hands around mine like a carpenter taught to measure twice and cut once—methodical, grateful.

Months passed, and then a year. The days softened. I kept up some of the rituals Helen and I had made—the garden needed tending and the roses she had wanted finally came into being in a way that felt like forgiveness planted in soil. I bought a small house in a neighborhood that smelled of jasmine and repair. I loaned funds in ways that felt moral: Anna’s trust for her children’s education, donations to cancer research in Helen’s name, and investments in a small construction outfit Robert started that hired veterans—men who needed work and a stable hand.

I did not visit Jason for a long time. It took months before my chest could hold the idea of seeing him behind glass. Anna went, and returned with reports. He was quieter, she said. He had lost weight. He read more. He worked in the prison library. He had questions about me. That opened something in me. Year two, I drove out. The visiting room smelled like disinfectant and hot coffee. He looked older. The arrest and the courtroom, the moral collapse and then the work of it, had dug into him. He sat across the table and looked at me for a long time without speaking.

“Why?” I asked him finally, because it was the only question that mattered.

He gave me the answer I had feared. “We were drowning,” he said. “Vanessa kept saying we were drowning. I was so tired of being left behind. I looked at you and I forgot what a father was.” His hands trembled. “I’m sorry.”

“Sorry doesn’t fix anything,” I said, honest as a beam in the sun. “But it’s a start.”

We talked then like two men who had once shared sandwiches and Sunday rituals and now had to relearn how to inhabit the spaces between regret and forgiveness. He told me about the jobs he’d had in the prison—stacks he’d sorted, books that had been his only companions. He told me about the weight of having people look at him as if the stain were permanent. I told him about the roses, about Robert and the fund, about Anna’s children. Not to boast, but to reclaim the ledger of life that was not measured solely in dollars.

When he got out after three years and two months for good behavior and programs, it felt like a small miracle. He moved into a halfway house near a hardware store and found work that roughed his knuckles but steadied his mind. He called every week. I answered. He asked for nothing—no handouts, only the chance to rebuild. I gave him a letter of recommendation from Carl, an old friend who ran a construction company. The job was honest, the kind of work I’d known all my life. He took it with shaking hands and stayed.

Time did a strange thing. It softened the raw edges but did not erase the line where grace had to meet justice. I did not funnel the remainder of the lottery into Jason’s hands. I placed his children—if he had any in the future—in a trust for education, funds they could not access until 25. I believed that if someone was to be helped, it should come with conditions that protected both him and the good people around him.

Vanessa disappeared after her release. She moved to Nevada, changed her name, and began again. I never saw her. I hoped she found what she had sought in money—if that thing could be found on a desert highway. Anna said she didn’t want to fill me with false hopes. “She’s a chameleon, Dad,” she said, “maybe she changed for the better.” I wanted to believe her. But the wound had been done.

The money did not, in the end, fix everything. It made things possible. It paid for medical bills I hadn’t anticipated. It set up Robert with a business loan. It paid for a scholarship in Helen’s name for children of nurses at County General. But money also revealed the brittle places in people. It showed me that some people see other people as amounts on a ledger and that sometimes, the truest work of wealth is deciding what good you will do with it.

There were small, important moments that grew like moss between the large stones of trauma. A Saturday morning when Anna called and read jokes off the phone. A letter from Jason describing a co-worker who taught him how to program a drill press. Robert texting pictures of his daughters on graduation day. An old neighbor knocking and bringing a pie. Each one stitched the world.

One evening, three years after the trial, I took Jason to the diner Helen liked—Mugs Without Chips, a little place that smelled like bacon and peppermint. We sat in a booth softened by time. He looked up from his coffee—real coffee, poured into a cup without a chip—and said, “I don’t expect forgiveness.”

“You don’t deserve it,” I answered, honestly. “You should have thought about that before you poured a pill into a cup.”

He nodded. “I know. I don’t expect it in full. I just want to try to be a person you’d want to live next to.”

“I can’t promise things,” I said. “But I can help you get a start. Clean slate comes with work. Carl’s hiring. It’s honest labor. You’ll keep your head down and do the work. You show me you can keep a steady job, you’ll show me you can be trusted.”

He laughed once—brittle and then something like a new sound, tentative. “I will,” he said. “I’ll never hurt you again.”

We ate. We talked. It wasn’t a miraculous fix, and it wasn’t anything like the family dinners of the past. But it was an offering, and that was something. Helen had told me once, leaning on an elbow, that money didn’t change the heart. Hardship revealed it. I thought of that often.

After Jason’s release, he and I planted a bench in the garden where Helen had wanted roses. We planted two roses—one red and one pale yellow. He did most of the heavy lifting; my back protested but my hands were steady. We spoke about small things: the way mortar should sit before you lay brick, the old rhythm of construction, how to pick a nail that won’t bend. He told me about the library at the prison and a man who had taught him to hold responsibility. I told him about Carl’s projects and the way the town had changed.

Years later, I would stand by the window on a morning when the roses were in full riot. I’d sip coffee from a chipped mug—not the one from the hospital, never that one—but a mug that had held the taste of breakfasts and the warmth of hands that had loved me. Jason had a new steadiness about him. He came by on Saturdays and mowed the lawn like it was penance, or prayer, depending on the day. He had a rhythm now that belonged to sobriety and work. He taught a young man at Carl’s crew how to set a beam straight. He kept his phone close to his chest and called once a week. The calls were short and full of news about which tool broke and what client needed what, but they were communion—the way small, steady things become holy gestures after they survive a storm.

What felt truest to me was not the money itself—it was what I did because of it. I could have bought a bigger house, a better car, an unending succession of things to sit in an empty heart. Instead I chose to keep one small house, keep Helen’s handwriting on a recipe card, plant roses in her garden, fund nurses’ scholarships, and invest in the men and women who needed a steady job and a hand up. I told myself often that the only fortune worth having was the one that brought more people to safety than it did to jealousy.

People asked me, in interviews and at community meetings—the paper wrote a small profile the year I set up the scholarship—if the money had made me happy. The question was blunt in its gentleness. “Happiness is an odd thing to measure by dollars,” I told them. “It helps pay medical bills. It opens doors. But the thing that matters doesn’t have a price tag. It’s the chance to keep trusting people until they teach you not to. It’s the chance to fix the roof and to plant a rose bush for the woman who dreamed of it.” The reporter nodded and wrote something about humility. I was not humble in everything—I took pleasure in the roses—but I was cautious in my joy.

There was a verdict I came to slowly, like a carpenter reading wood grain. Money, I learned, is a kind of mirror. It does not create a person’s character; it reflects what is already there. If you are generous, money multiplies your generosity. If you are greedy, it gives you the tools to wreak more damage. That is a bitter truth. It is also the kind of truth that allows for repair, given time and effort.

Seven years after the scratch-off, I was buying a ticket at the same 7-Eleven because some habits are prayers dressed as rituals. A young woman in front of me dropped her wallet. I handed it back. “Thank you,” she said, squinting at me. “Wait—you’re Daniel Dawson, the lottery winner, aren’t you?”

I smiled the sort of small smile that contained a lot of road. “I used to be,” I said. “Now I’m just Daniel.” She told me about an argument with her father, money troubles and all. I had advice that had nothing to do with investments and everything to do with hearts: “Call him. Tell him you love him. Money can push people away, but the reason to call is because people matter more than the things they want from us.” She paused, considering, then said she would.

The days moved forward like a machine carefully oiled. Jason married again—someone who liked art and had worked at the library, a woman who loved bluebirds and, I suspected, saw something tender in my son. They had two children. My grandchildren, if I could say such a thing, came to the house and stained the table with jam and made fortresses for which I supplied the wood. Jason took on the role of father slowly and with a humility that looked like thanksgiving. He taught the boys how to hammer a straight line. He taught them to whisper the names of tools like prayers. It was not a reward to me; it was redemption.

Sometimes, at dusk, I would sit on the bench in the garden and watch a man who had once tried to kill me with a cup of coffee teach his boy to hold a hammer properly. I would remember the hospital and the chip on the cup and the searing hurt. Then I would think of Robert, who had been present and brave enough to trust his own eye; of Anna, whose loyalty had been a steady light; and of the roses, which were not trophies but memorials to what we could not take back and what we could steward forward.

On the last day of my sixty-eighth year, I walked the neighborhood and dropped by the 7-Eleven to buy a ticket. The cashier gave me a look like people give to men who have been on the weather of life long enough to know how storms end. “You going to keep doing this?” he asked.

“It’s our ritual,” I said. “Helen liked that. She believed in small, stubborn hope.”

He rang me up, and I paid with cash because I liked the sound of coins. Driving home, the roses caught the last light, and I thought of how easy it is to let money define a story. It had been a prism in which people’s true colors showed. It had torn my family and then, in other ways, allowed it to be mended.

No narrative I could have predicted would have entailed standing beneath the roses with Jason by my side, smelling earth and possibility. We had been through a valley of consequences and had come into a plain where work and sorrow braided themselves into something like peace. I did not forget the betrayal. I had not been a man who could forget that. But I also did not live as a man whose heart was permanently closed.

“You ever regret it?” Jason asked one evening as we sat on the back stoop, the children inside arguing over a broken toy.

“Regret?” I repeated, because the night carried our breath. “I regret what happened. But I don’t regret fixing what I could. Regret is a heavy bag. I prefer to carry tools.”

He laughed, and then he rested his head against mine for a moment, in that odd, unspoken way fathers and sons sometimes find when they stop trying to be perfect for each other.

The money, the headlines, the trials, all of it became a story the town would tell with a kind of exhale. I became “the lottery man” in the paper and “the man who gave scholarships” at community dinners. Jason became someone who had fallen and then climbed, his hands raw and honest. Vanessa became, in the stories I heard later, a ghost who lived under a name change and the softer things the law allows for those who leave.

In the end, light does not come from money. It comes from choices—little ones and large—made over and over again. I chose to use wealth to make good things happen. I chose also to make room for my son to fail and to seek the hard work of repair. I think Helen would have approved. She always said money couldn’t buy character, but hardship could reveal it. We had both been right in different ways.

Some mornings, I still buy a ticket out of habit, and sometimes I scratch it off with the memory of Helen’s laugh. The roses bloom every May like a small miracle. Jason calls on Sundays. Robert’s company is thriving and he sends me a photo from time to time of veterans in hard hats grinning against a sky. Anna’s kids are grown and responsible, and they know Helen by name and in stories. On afternoons when the world is kind, I sit on the bench we put in the garden and look at a life that had its darker chapters but also its long, quiet arcs toward mercy.

If there’s a moral, it is not a neat one. Money reveals. People choose. Sometimes they fail. Sometimes they hold hands and repair. The world is rough and sometimes cruel, but it is also full of people who will record inconvenient footage and step forward when the moment calls them to be brave.

One day, when the roses were at their fullest, a young man stopped by the gate and asked if he could sit. He was twenty, he said, and wanted to know if a man could change after making a terrible mistake. I thought of Jason and the hours we spent shifting bricks and shifting forgiveness. I told the boy, without grandness, “Yes. But it takes a lifetime of small things. You don’t ask for forgiveness and walk away. You stay and you work. You tend the roses.” He listened, and then he left with a strange look—half hope, half fear.

I watched the gate close and the roses glow and thought of Helen, whose hands had imagined gardens even when it was hard to imagine the future. Money had changed my address. It had not changed the need to be human. In the end, the richest thing I owned was not the account tied to a bank, but the stubborn, patient work of being a man who, when hurt to the core, could still find a path toward what would nourish rather than destroy.