When I dropped out of college at twenty, my sister didn’t just whisper about it behind closed doors. She announced it like a verdict.

“She’s the family failure,” Lauren Chen told anyone who would listen, shaking her head with the satisfaction of someone relieved it wasn’t her.

At family dinners, my name became shorthand for what not to become. Cousins were warned not to “end up like Hannah.” My parents avoided my eyes. Lauren wore my struggle like a medal, proof that she was the responsible daughter, the one who stayed on the approved path.

The truth was messier. I didn’t drop out because I was lazy. I dropped out because my mother got sick, because bills piled up, because I worked nights and couldn’t stay awake in lectures. I dropped out because life didn’t care about my transcript.

But explanations don’t matter to people who prefer labels.

So I left. I worked. I rebuilt quietly. I earned my degree later through night programs. I pursued graduate school when I could afford it. I became the person who read applications instead of begging to be accepted.

Twelve years passed like pages turning.

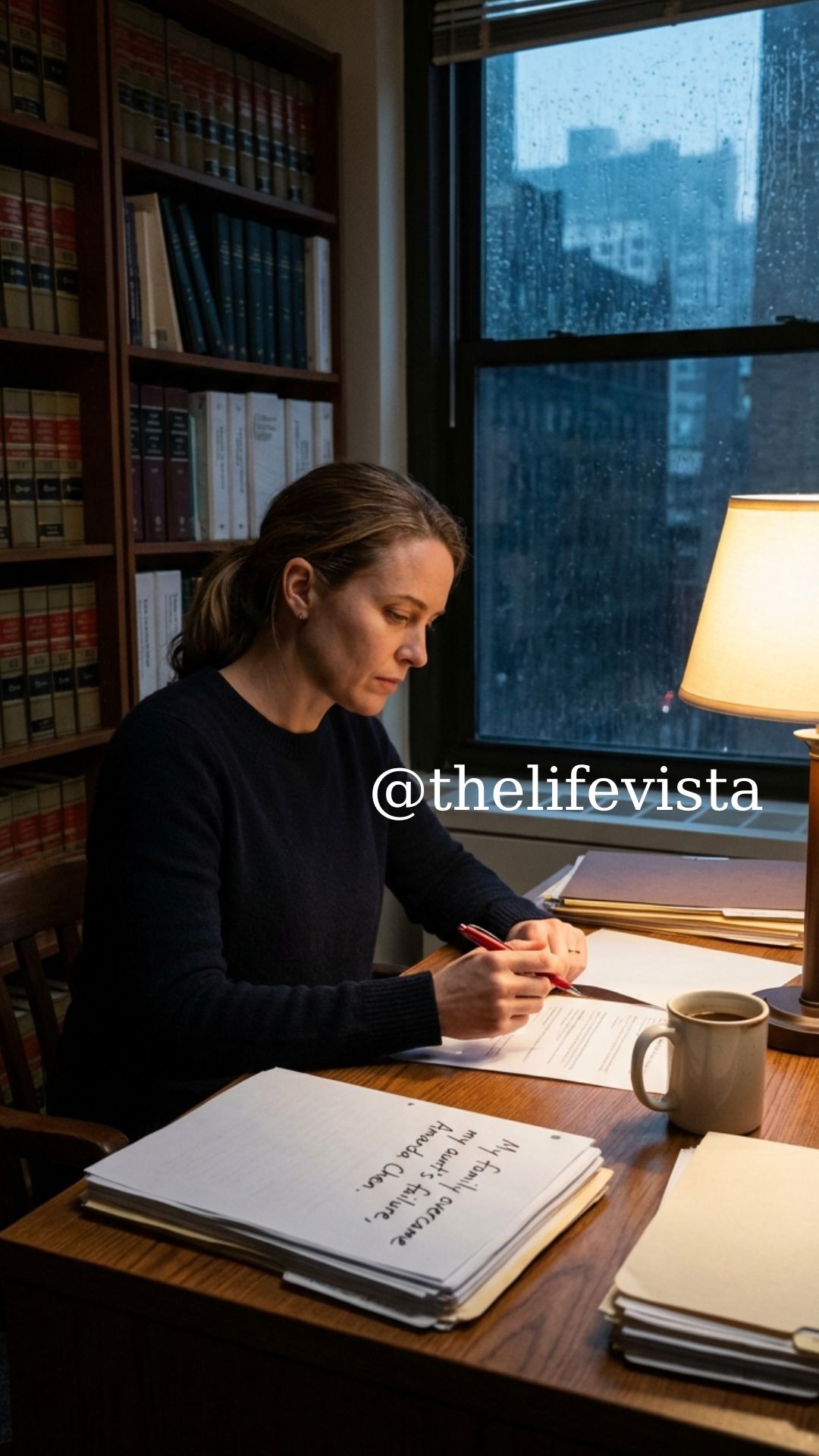

Now, at thirty-two, I sat in an office lined with books and winter light, my name printed neatly on the door:

Hannah Chen, Dean of Admissions, Yale University.

It still felt surreal sometimes, not because I doubted my work, but because the version of me Lauren mocked would never have imagined this room.

That afternoon, the admissions cycle was in full swing. My desk was stacked with essays—dreams condensed into personal statements, each one asking the same silent question: Do I belong here?

I opened another file, expecting the usual themes: resilience, leadership, loss.

The applicant’s name made my hand pause.

Brianna Chen.

My niece.

Lauren’s daughter.

I hadn’t seen Brianna in years, not since she was a child clutching a stuffed rabbit at Thanksgiving while Lauren corrected her posture. I knew Lauren had raised her like a project, a future trophy.

Curiosity tightened in my chest as I clicked the essay.

The first lines were polished, confident.

Then my eyes caught a sentence that made the air leave my lungs.

“My family overcame my aunt’s failure,” Brianna wrote. “She dropped out at twenty and became a cautionary tale that motivated the rest of us to succeed.”

I stared at the screen, feeling something old and sharp twist beneath my ribs.

Aunt’s failure.

Cautionary tale.

Motivated.

Lauren’s voice echoed through the words like a ghost: She’s the family failure.

Brianna continued, describing how her mother “carried the family forward” while an unnamed aunt “fell behind.” It wasn’t cruel in a childish way. It was cruel in a rehearsed way, like she’d been taught the story and rewarded for repeating it.

My fingers hovered over my red pen.

Admissions was supposed to be objective. Fair. Blind to personal history.

But this wasn’t just an essay.

This was my life, rewritten into someone else’s inspirational anecdote.

I leaned back slowly, staring at Brianna’s name at the top of the page, and felt the weight of choice settle into my hands.

I picked up my red pen and…

paused.

Because what I did next would reveal whether I was still the family’s “failure”…

or the one person who could finally break the story apart

The hardest part of being labeled a failure isn’t the word itself.

It’s how quickly people stop asking what happened.

When I left college at twenty, I packed my dorm room in silence. My roommate offered awkward sympathy. My advisor said, “Maybe you can come back someday,” in the tone people use when they don’t believe it.

I took a bus home with two suitcases and a stomach full of dread.

My mother was in the hospital by then, her skin waxy, her hands thinner than I remembered. My father sat beside her bed looking older than his age, bills stuffed into his coat pocket like hidden shame.

Lauren met me at the door when I came home.

“Well,” she said, arms crossed. “So it’s official.”

I didn’t even have the energy to argue. “Mom needs help,” I said.

Lauren scoffed. “Mom needs help, yes. But you dropping out? That’s on you.”

It wasn’t on me. It was on circumstance. On poverty. On caregiving. On exhaustion. But Lauren didn’t want nuance. Nuance didn’t give her a pedestal.

For years, she told the story like this:

Hannah quit. Hannah wasted potential. Hannah became the example.

And I let her, because fighting her narrative felt like screaming into fog.

Instead, I worked.

I took a job at a community center doing administrative support. I learned how systems worked from the inside—how funding was allocated, how education changed lives beyond classrooms. I watched teenagers apply to colleges with hope and fear in equal measure.

One day, my supervisor, Mrs. Vivian Graves, found me staying late to help a student edit an essay.

“You have a gift,” she said.

“For grammar?” I joked.

“For seeing people,” she corrected. “And for believing they belong somewhere bigger.”

That sentence stayed with me.

I enrolled in night classes at a state university. It took longer. It was harder. But it was mine. I graduated at twenty-five, not with fanfare, but with quiet pride.

Graduate school came next. Then a doctorate in education policy. Then years of work in admissions and access programs, fighting for students who were brilliant but underestimated.

By thirty-two, Yale offered me the position of Dean of Admissions—young for the role, but not unearned.

Lauren sent a text when she heard.

Congratulations. Didn’t expect that.

No apology. No acknowledgment of the years she’d used my name as a warning.

I didn’t reply.

So when I opened Brianna’s essay, I wasn’t just reading a teenager’s words. I was reading Lauren’s legacy poured into her daughter’s mouth.

Brianna wasn’t evil. She was shaped.

Still, shaping becomes choice eventually.

The essay was technically strong: vivid imagery, clear structure, emotional hook. But the hook was my humiliation.

I could already imagine Lauren coaching her:

“Admissions officers love resilience stories. Mention how our family overcame hardship. Mention your aunt—don’t name her, just imply.”

And Brianna had named me.

I sat there for a long time, staring at the cursor blinking beneath her last sentence.

Admissions ethics demanded fairness. Personal grudges had no place in decision-making.

But admissions also evaluated character.

And this essay revealed something uncomfortable: a young woman willing to step on someone else’s back for a narrative of success.

I uncapped my red pen.

Not to punish.

To tell the truth.

I began marking.

Not the grammar.

The meaning.

In the margins, I wrote:

Failure is not leaving school. Failure is refusing compassion.

I underlined “cautionary tale” and wrote:

Have you asked your aunt why she left?

I circled “motivated” and wrote:

Is someone else’s struggle your inspiration—or your excuse?

I wasn’t sure yet what decision I’d make about her application. That wasn’t mine alone. Yale admissions was committee-based, structured to prevent exactly this kind of bias.

But I could request an interview. I could flag concerns. I could also choose silence.

Then my phone buzzed.

A number I hadn’t saved, but I recognized.

Lauren.

I stared at it, then answered.

“Hannah,” Lauren said brightly, too brightly. “Funny coincidence. Brianna applied to Yale. Isn’t that wonderful?”

My grip tightened. “I’m aware.”

Lauren laughed. “Of course you are. I’m sure you’ll take good care of her file.”

There it was. The assumption. The entitlement.

“I’ll do my job,” I said evenly.

Lauren lowered her voice. “This could be a beautiful family redemption story, don’t you think? My daughter at Yale, guided by her aunt who… found her way eventually.”

Found her way.

As if I’d been lost.

As if she hadn’t shoved me.

I exhaled slowly. “Lauren,” I said, “have you read Brianna’s essay?”

A pause.

“…She showed me a draft,” Lauren admitted.

“Did you notice what she wrote about me?”

Another pause, longer.

“She didn’t mean it badly,” Lauren said quickly. “It’s just… context. Admissions people love overcoming adversity.”

“So you taught her to use my life as adversity,” I replied.

Lauren’s tone sharpened. “Don’t make this personal.”

I almost laughed. “You made it personal twelve years ago.”

Silence crackled.

Then Lauren said softly, dangerously, “You wouldn’t sabotage your niece.”

I felt something settle inside me, calm as stone.

“No,” I said. “I wouldn’t sabotage her.”

Then I added, “But I also won’t let you keep rewriting me as a failure.”

Lauren’s breath hitched. “Hannah—”

“I’m requesting an interview,” I said. “Brianna deserves to speak for herself, not through your narrative.”

Lauren’s voice rose. “That’s unnecessary!”

“It’s necessary,” I replied. “Because if Brianna is going to Yale, it should be because she understands truth, not because she learned how to package cruelty.”

I ended the call before she could respond.

My hands were steady again.

The red pen rested beside the essay.

And the next step wasn’t revenge.

It was accountability.

Brianna arrived on campus in early March, wrapped in a wool coat too expensive for a teenager to have chosen alone. Her posture was perfect, like Lauren had trained her spine.

She sat across from me in my office, hands folded neatly in her lap. Her eyes flicked once to the nameplate on my desk.

Hannah Chen.

For a moment, she looked like she might finally connect the dots.

“Thank you for meeting with me,” she said politely.

“You’re welcome,” I replied. “I wanted to speak because your essay was… memorable.”

Brianna’s lips curved nervously. “My mom said it would stand out.”

I nodded once. “I’m sure she did.”

Silence.

Brianna shifted. “Is something wrong?”

I leaned forward slightly. “Brianna, do youyou know who I am?”

Her cheeks flushed. “You’re Dean Chen.”

“And outside this office?”

Brianna hesitated. “You’re… my aunt.”

“Yes,” I said gently. “The aunt you described as a failure.”

Brianna’s face went pale. “I—”

I held up a hand, calm. “I’m not here to shame you. I’m here to ask something simple. Did you write those words because you believe them, or because you were taught them?”

Brianna’s eyes filled quickly, panic rising. “I didn’t mean it like that.”

“How did you mean it?” I asked.

Brianna swallowed hard. “My mom always said… you were the example. That you quit. That it made her stronger. That it made our family push harder.”

I nodded slowly. “Did she ever tell you why I left school?”

Brianna’s voice dropped. “No.”

“I left because your grandmother was sick,” I said softly. “Because we couldn’t afford care. Because I worked nights to keep the lights on. That wasn’t failure. That was survival.”

Brianna stared at me, tears slipping down her cheeks. “I didn’t know.”

“I know you didn’t,” I said. “But you used the story anyway.”

Brianna’s shoulders shook. “I’m sorry. I thought admissions wanted… hardship.”

“Admissions wants honesty,” I corrected. “Not cruelty dressed up as resilience.”

Brianna wiped her face quickly, embarrassed. “My mom said if I made it emotional, it would help.”

I exhaled. “Your mother has always been good at using people’s lives as tools.”

Brianna flinched. “She’s… intense.”

“She’s controlling,” I said plainly. “And you’re old enough now to decide whether you continue that pattern.”

Brianna looked down. “I don’t want to be like that.”

“Then start now,” I said. “Tell me who you are without stepping on anyone else.”

For the next thirty minutes, Brianna spoke differently. Less rehearsed. More real. She talked about loving biology, volunteering at a free clinic, wanting to become a doctor because she hated watching illness turn families into strangers.

She spoke about pressure. About never feeling enough. About Lauren’s obsession with perfection.

When she finished, she whispered, “Do you think I ruined my chance?”

I considered her carefully.

“I think,” I said, “you revealed something important. Not just about you, but about the environment you were raised in.”

Brianna’s breath trembled. “So… what happens now?”

“Now,” I said, “I submit my notes to committee. I don’t decide alone. But I will say this: growth matters here. Accountability matters.”

Brianna nodded, tears still shining. “I want to rewrite it. The essay. Not for admissions. For you.”

I gave a small, sad smile. “Rewrite it for yourself first.”

A week later, the committee met. Brianna’s application was strong academically. The essay was a concern, but the interview notes showed self-awareness and genuine remorse.

She was offered admission—with a recommendation for mentorship support, away from parental interference.

When Lauren found out, she called me furious.

“You let her in after what she wrote?” she demanded. “After she mentioned you?”

“I let her in because she’s more than your narrative,” I replied calmly. “And because she apologized without excuses.”

Lauren’s voice sharpened. “You think you’re some hero now.”

“No,” I said. “I think I’m finally done being your cautionary tale.”

Silence.

Then, quietly, I added, “Brianna will be fine. The question is whether you’ll ever stop needing someone else to be the failure so you can feel like the success.”

Lauren hung up.

That night, I sat alone in my office, red pen resting beside a stack of essays. I thought about the girl I’d been at twenty, leaving school with shame in her suitcase. I thought about how easily families turn survival into scandal.

And I realized something:

Success isn’t the title on my door.

Success is refusing to pass cruelty down another generation.

So if you’ve ever been labeled a “failure” by someone who needed you beneath them—what would you do when the story comes back around? Would you punish, forgive, or choose the harder path: telling the truth and breaking the cycle?

I’d love to hear what you think.