I slept in my car so my daughter could have a bed, and when people hear that sentence now, they tilt their heads and react as if it belongs to a movie or a charity poster, something dramatic and distant, something that happened to someone else in a different world. Back then, there was nothing poetic about it, no sense of sacrifice that felt noble or heroic, only the quiet math of survival and the relentless knowledge that there were not enough dollars to cover both rent and dignity at the same time.

The first night I slept in my car, I told myself it would be temporary, a short detour from normal life rather than a destination, a week at most, maybe two, just until overtime came through or a bill got delayed or something, anything, shifted in my favor. I parked behind the apartment building where my daughter and I lived, far enough back that no neighbor would notice me climbing out of the driver’s seat in the dark, close enough that I could still look up and see the outline of her bedroom window and tell myself that being nearby counted for something.

Her name is Ava Reynolds, and when this story began, she was seven years old, small and quiet, with a habit of curling into herself when she slept as if she were apologizing for taking up space in the world. That night, I tucked her into bed the same way I always did, smoothing her hair, pulling the blanket up under her chin, making my voice sound steady as I told her goodnight, even though my chest felt tight and my thoughts were already sinking toward the parking lot.

She smiled at me, half-asleep, and said goodnight back, and I kissed her forehead, turned off the light, and walked out of the apartment like nothing was wrong. I took the stairs slowly, listening to my own footsteps echo, and when I reached the lot, I climbed into my old sedan and shut the door as quietly as I could, folding my body into the driver’s seat because the back was too cluttered to stretch out.

It was late autumn in Michigan, the kind of cold that creeps in rather than announces itself, and every breath fogged the windows instantly. I kept the engine off to save gas, wrapped myself in a jacket that still smelled faintly of Ava’s shampoo, and told myself to sleep. I did not sleep. I watched the light in her bedroom window until it went dark, and then I stared at the dashboard until the sky began to pale.

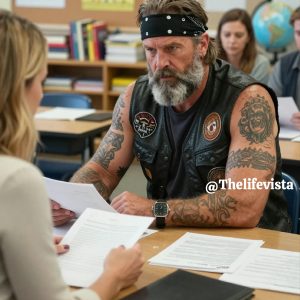

People think homelessness looks a certain way, like cardboard signs and crowded shelters and visible desperation, but mine looked like a clean-shaven man in steel-toe boots clocking in at a warehouse before sunrise and brushing his daughter’s hair before school. Ava never knew where I slept. She thought I worked late. She thought I sometimes crashed on the couch because I snored. She thought her father was tired because work was hard. She thought everything was fine.

At school, she had what she needed. She had a bed. She had a desk. She had lunches I packed the night before, sitting in the car under a flickering streetlight. At night, I learned which parking spots were safest, which gas stations tolerated overnight cars, which nights were so cold that sleep was impossible and pacing was better than shivering.

Once, Ava wrinkled her nose and asked why I smelled like cold metal, and I laughed it off, telling her I was a superhero and that superheroes did not always sleep, and she laughed with me, and later I cried quietly in the car because the lie tasted bitter and necessary at the same time. The truth was simple and brutal: if I slept inside, there would not be enough money for rent, and if I slept in the car, my daughter had a bed, so I chose the car again and again without ceremony.

The years passed like that, quietly and painfully, and the hardest nights were not the cold ones but the nights when Ava got sick. I would sit in a plastic chair in the emergency room at three in the morning, pretending my exhaustion was normal while nurses glanced at my worn jacket and the way my eyes tracked security guards with too much awareness. Once, a nurse asked gently if I had somewhere to go after we were discharged, and I said yes without hesitation because the truth felt dangerous.

Another time, Ava’s teacher called to mention that her shoes were wearing thin and that there was a program that could help, and I cut her off too quickly, promising I would take care of it, because pride has a cost and I was already paying more than I could afford. There were nights I thought about giving up custody, about admitting I could not do this alone, about letting Ava’s mother take over, but her mother had left years earlier chasing something larger than responsibility, sending birthday cards and apologies instead of money or presence.

One winter, my car refused to start, and I spent the night sitting upright in a bus station, clutching my phone and praying no one would call Child Services before morning. I washed my face in a sink before picking Ava up for school, and when she told me I looked tired, I said I was fine, and the lie felt heavier than any coat.

When Ava turned ten, she asked why we never moved, and I told her this place had memories, leaving out the part where landlords do not rent to men with maxed-out credit and empty savings. When she turned twelve, I caught pneumonia, missed three days of work, and came terrifyingly close to losing everything. Sitting in the car that night, shaking with fever, I whispered that I could not do this anymore, and then the next morning, Ava smiled at me over breakfast and told me I always showed up, and something inside me steadied.

I showed up to parent-teacher conferences smelling like cold air. I showed up to school events in borrowed jackets. I showed up to birthdays with homemade cakes and apologies for small gifts. Ava grew taller and louder, and I grew quieter, carrying the weight of years in my bones, until one day everything changed in a way I never expected.

I slept in my car so my daughter could have a bed, and I never thought she would tell anyone. The day Ava graduated high school, I almost did not go because my jacket was frayed and my shoes were worn and I still lived paycheck to paycheck, but she insisted, and I found myself sitting in the back of a packed auditorium surrounded by proud parents in pressed clothes.

When her name was called, Ava walked across the stage with a confidence that stole my breath, took the microphone, and began speaking about resilience. She talked about a man who never missed a day, even when it would have been easier to quit, and as her eyes found mine in the crowd, my heart began to pound.

She told them that for years she thought we were just poor, that she thought I was tired for no reason, and then she said the words that froze the room, explaining that while she slept in a warm bed, her father slept in his car so she would not have to worry. She pointed at me and named me as the man who never gave up on her, and I could not stand because I was crying too hard.

Afterward, she hugged me and whispered that she knew now, that she knew everything, and when I apologized, she shook her head and thanked me instead. Years later, Ava bought a house, handed me a key, and told me I would never sleep in a car again. Now, when people hear my story, they call me strong, but the truth is simpler and quieter, because I was just a father who chose the driver’s seat so his child could rest in the light, and love, most of the time, does not look heroic at all.