CHAPTER 1: THE LETTER THAT STOLE THE MORNING

The quiet of a Montana sunrise was never empty; it carried weight, cool and clean, edged with the scent of damp pine needles and hay that had cured in the loft all winter. Graham Hollis stood on the porch of his farmhouse while the first light crept over the ridgeline, and the old cedar boards beneath his boots answered each shift of his stance with a familiar, tired creak. He held a chipped ceramic mug in both hands, and the steam from his coffee rose in thin spirals that disappeared into the crisp air as if the morning were swallowing every warm thing it could reach. Beyond the porch railing, fifty acres of stubborn land rolled out in uneven waves, a patchwork of grasses and sage and fence lines that had been repaired so many times the repairs felt older than the originals, and the whole place looked like it had been built not just with lumber and nails but with years a man couldn’t buy back. That ground had carried the Hollis name through the Depression, through wars that took young men and returned them older, and through dry seasons that made the creek shrink into a ribbon of stone, and it had never asked the family for permission to be itself.

At the end of the gravel drive, the mailbox stood alone like a sentry that never got to go inside, its post grayed by weather and its metal door pocked with tiny dents from years of wind-driven grit. Graham set his mug on the porch rail, then walked down the drive in long, steady strides, letting the crunch of gravel under his boots settle his mind the way it always did when something felt off. When he opened the mailbox, he found bills and flyers like usual, but one envelope sat on top like a clean tooth in a mouth full of stains. It was bright white, stiff, and so pristine it looked like it had never been touched by real work, and the sharp corners made it seem almost arrogant out here where everything else had been softened by weather and time. The return address was printed in crisp black ink: Pinecrest Hollow Homeowners Association — Office of the President, and the words landed wrong because Graham didn’t belong to any association that used that kind of language.

He tore the envelope open with a calloused thumb and pulled out the letter, and the first line didn’t offer a greeting or a courtesy, it offered a verdict. The header read, “RE: Formal Annexation and Community Access Rights Regarding Parcel 117-Hollis.” His eyes tracked downward, and as the meaning settled, a slow, heavy thud began in his chest, not panic, but the first drumbeat of anger trying to stay polite. The letter claimed that due to “historic public use” and a “recent boundary audit,” his ranch was no longer to be treated as private land, and the north pasture had been reclassified as “Shared Recreational Open Space” for the benefit of Pinecrest Hollow residents. Graham whispered the phrase to himself, because saying it out loud made it feel even more absurd, and the cold in his gut had nothing to do with the wind. He looked up toward the low hills where his grandfather had dug post holes by hand, and he remembered the spot by the creek where his father had bled after a barbed-wire snap caught him deep, and he felt the insult settle into the soil of his bones.

The letter continued with the kind of calm certainty that only people who think they can’t be stopped ever use, stating that as of Monday the gates on the Hollis property were to remain unlatched to allow “unimpeded flow” for walkers, dog owners, and families seeking outdoor enrichment, and it added that failure to comply would result in daily penalties of five hundred dollars. Graham read that number twice, not because he didn’t understand it, but because he understood it too well, and he felt the shape of a siege forming around him. This wasn’t a misunderstanding, and it wasn’t an accidental misdelivery. It was a plan, and the plan assumed he would be too isolated, too tired, or too decent to push back hard enough to matter.

From the edge of his property, he could see where the valley had changed in recent years, where the neat sprawl of Pinecrest Hollow had begun to bleed toward his fence line like a slow tide of white shutters and manicured lawns. Those houses hadn’t arrived all at once; they had crept forward in small increments, each new build bringing streetlights and sidewalks and residents who looked at open land like it was waiting to serve them. Graham had lived through that creep with clenched teeth and forced smiles, because he couldn’t stop the valley from growing, and he wasn’t interested in being the man who hated newcomers simply for arriving. What he could not accept was a piece of paper telling him that kindness and patience had now become legal weaknesses.

He walked back to the house with the letter crumpled in his fist and didn’t touch the coffee again, because the taste of it suddenly felt too calm for what the morning had become. Inside the living room, he went straight to the roll-top desk that had belonged to his grandfather, pulled open the drawer that stuck unless you lifted slightly, and dragged out a leather binder that smelled like dust and old ink. In it were the original deeds and hand-drawn maps on yellowed paper, documents signed by men who didn’t hide theft behind phrases like “community access.” Those papers weren’t just legal proof; they were the family’s spine, and seeing them made his anger sharpen into something steadier.

The house phone rang, and the sound was too loud in the quiet rooms, like a bell in a church when nobody expects it. Graham picked up the receiver, and his voice came out low and rough when he answered. A woman’s voice greeted him with brightness so polished it sounded practiced, and she introduced herself as Vivian Ketter, president of the Pinecrest Hollow HOA, asking if he had received their “information packet.” Graham told her he had received a letter, and he kept his words controlled as he said that he believed they had sent it to the wrong address because his land was private and had been private for generations. Vivian didn’t apologize; instead she offered a small pause that felt like the moment before a person decides to correct you, and she said, with the gentle tone of someone explaining something obvious to a stubborn child, that the valley was changing and residents needed space for walking paths and family activities. She added that his land had been “informally enjoyed” for years, and that the association had simply formalized what had already been true, because progress required shared resources.

Graham told her that “shared” didn’t pay his taxes, and “informal enjoyment” had never replaced a deed, and the calmness in his voice carried a warning that he didn’t bother dressing up as friendliness. Vivian answered that fences were divisive, that community unity mattered, and that the paperwork had already been filed with the county clerk, so if he tried to obstruct residents, the association would involve law enforcement. While she spoke, Graham’s gaze moved through the window, and he saw a silver crossover idling near his gate, and a woman stepped out holding a golden retriever on a leash like she was walking into her own backyard. The woman glanced at the gate, then at a piece of paper in her hand, and she began to work the latch on the chain Graham had hung years ago. Graham told Vivian that trespassing was still trespassing, and her reply came soft and chilling as she said, “No, Graham, we’re returning to what belongs to the neighborhood.” He hung up without another word, because there was no point in arguing with someone who had already decided the ending.

He watched as the woman and her dog stepped onto his grass, and the dog lifted a leg against a fence post his father had set forty years earlier, and the woman smiled at the view like it was a perk included in her mortgage. Graham’s hand shook, not from fear, but from a deeper rhythm, the kind that comes when a person realizes he’s being tested on whether he still believes he has the right to exist as himself. He put on his hat, walked to the tool shed, and told himself that if Vivian Ketter wanted his land, she was going to learn that some ground still has thorns, and those thorns don’t care about silk scarves or polished voices.

CHAPTER 2: THE COUNTY OF PAPER AND TEETH

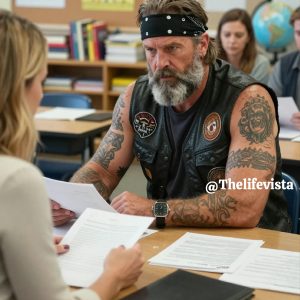

The law office of Caleb Rourke smelled like old bindings, stale coffee, and the faint bite of tobacco that had soaked into the walls decades earlier. It was a cramped building in town with a ceiling that felt too low and shelves packed so tight with books and files that the air itself seemed weighted by all the arguments those pages contained. Caleb sat behind a heavy wooden desk scarred with scratches and dents from generations of frustrated hands, and he wore thick glasses that caught the morning light and hid his eyes until he tilted his head just right. He was a big man with a slow, deliberate way of moving, like someone who had learned not to waste energy on anything that didn’t matter, and when Graham slammed the crumpled HOA letter onto the desk, Caleb read it with the careful stillness of a doctor inspecting an infection.

When Caleb finished, his mouth tightened and his fingers stayed on the paper as if he didn’t want it to float away and pretend it had never existed. He asked Graham, with a gravelly disbelief that carried anger under it, what exactly the association thought it was doing, and Graham told him that Vivian Ketter believed she could sign words into reality and turn a working pasture into a public park. Caleb leaned back until his chair complained, and he said he had seen this kind of maneuver before, usually in places where people didn’t know their neighbors and didn’t notice land disappearing until the bulldozers arrived. He explained that it often involved a prescriptive easement claim, where repeated “use” is treated like entitlement, mixed with boundary games and filings that get buried in stacks of paperwork that nobody reads because reading it would take a lifetime. The strategy depended on the target being decent, patient, and slow to respond, and the moment Caleb said that, Graham felt his jaw tighten because he understood the trap: his family’s neighborliness was being recast as surrender.

Caleb pulled a thick folder from a cabinet and spread a map across the desk, and the valley looked different on paper, not alive and open, but segmented into shapes and colors like meat in a butcher’s case. Graham’s ranch was highlighted in a bright, predatory shade, and Caleb pointed to a thin line near the border where the new subdivision pressed close. He told Graham that when Pinecrest Hollow was plotted years earlier, someone filed a “conditional boundary adjustment” buried inside environmental reports, claiming Graham’s parcel was an “unincorporated resource” tied to the valley’s original land grant, and that the lie had sat in the county’s records long enough to start growing legs. Graham snapped that his great-grandfather purchased that land long before the subdivision existed, and Caleb agreed, but agreement didn’t erase the danger because the law doesn’t care what’s true if nobody forces the truth into the record.

Graham asked how to kill it, and Caleb’s answer wasn’t soft. He said they would make the lie so expensive to keep alive that the association would choke on it, and they would do it with paperwork sharp enough to cut. He warned Graham not to use force, not to give them a photograph of an “unstable rancher” threatening families, because Vivian would use that narrative like a crowbar to pry open the county’s sympathy. Instead, Caleb told him to create friction the legal way, to make the “shared space” so inconvenient, so costly, and so full of documented consequences that the HOA would regret the day they ever printed that letter. Graham asked what friction looked like, and Caleb told him it looked like records, signage, compliance, and a trail of invoices so detailed that no judge could pretend it was merely a feud.

On the way back home, Graham stopped at Granger Supply, a hardware store that smelled of galvanized steel, sawdust, and oil, the kind of place where the shelves hold practical solutions and the cashier knows your name because the town is still small enough for that. The owner, Walt Granger, leaned over the counter like a man who had been part of the valley’s bloodstream for decades, and he asked Graham what kind of project demanded that much wire. Graham told him he had new pests to discourage, and Walt didn’t smile, because he had heard the rumors already. Walt muttered that Vivian Ketter had been holding court at the community center, pitching the north ridge as the site for a “Sunset Stretch Series” and dog-walking trails, telling homeowners the view “belonged to everyone.” Graham’s eyes burned at the phrase, because it was the kind of entitlement that sounds noble when spoken slowly enough.

Graham loaded his cart with high-tensile wire, insulators, and low-voltage electric fencing equipment, the kind ranchers use to keep bulls from wandering into trouble, and he added warning signs because legal requirements matter when predators are hunting for a technicality. Walt rang him up and slid the signs across the counter—bright yellow with bold black letters that didn’t care about anyone’s “aesthetic”—and Graham paid in cash because cash feels final in a way checks do not. When he drove back toward the ranch, he saw teenagers parked near his gate, their skateboards leaning against his timber posts, soda cans tossed into his ditch like the world was a trash bin with no owner. He didn’t honk or yell because he understood that attention is currency, and he refused to spend it on anyone who expected it. He simply drove through the gate, letting dust rise and coat their shiny car, and he carried his anger home where it could be used for something useful.

That afternoon, Graham went into the shed and dug into family records the way a man digs for roots. In the bottom of an old cedar chest he found his grandfather’s ledger, thick and hand-bound, with pages filled in meticulous cursive. It tracked every bag of seed, every gallon of diesel, every fence post, every repair, every season that required work to survive, and as he flipped through it, he realized Vivian’s “historic use” claim was built from moments of grace. There were notes about allowing a neighbor to graze a few head for a short time in exchange for apples, and notes about letting the fire department practice a controlled burn without charge, and notes about Scouts camping by the creek back when Graham’s father still walked the hills. None of it was surrender, and none of it was a lease, but Vivian was trying to turn generosity into a chain.

Graham took a legal pad and started doing math with the cold precision of someone who has been forced to translate emotion into numbers. If the HOA wanted to claim the ranch had functioned as community space for twenty years, then the HOA had benefited from a service, and services have costs. He calculated market rates for land use, brush clearing, weed mitigation, fence repairs, and security patrols, and he added liability coverage because his insurance had protected every trespasser who hopped his fence for a sunset photo. The number grew until it stopped feeling like an estimate and started feeling like a weapon, and when he reached the end, he had a figure large enough to make any board meeting taste like ash.

That night, while the moon hung cold above the valley and the house ticked with the slow patience of old wood, Graham called Caleb and told him the invoice was ready, and he said that if Vivian wanted to play the history card, she was going to receive a bill for two decades of “community service.” Caleb’s voice on the line sounded grimly pleased, and he told Graham to keep documenting everything because documentation is what turns rage into victory. When Graham hung up, he stared at the ledger again and understood that the association wasn’t just after land, it was after narrative, because if they could rewrite the past, they could steal the future without looking like thieves.

CHAPTER 3: THE FENCE THAT SPOKE WITHOUT SHOUTING

Before dawn fully cleared the jagged ridge, Graham hauled the first heavy spool of wire from the truck bed, and the air bit his lungs with that brittle Montana cold that makes each breath feel sharp and clean. He worked without hurry but without softness, because the task required focus more than speed, and he had built fences before in storms, in heat, and in grief. This wasn’t about creating a prison; it was about restoring a boundary that had been chipped away by politeness and time. The low-voltage electric fence he installed was legal, agricultural, and designed as deterrence rather than harm, but it carried a message that couldn’t be ignored once it was in place. The wire itself was nearly invisible against sage and grass unless a person bothered to look, and Graham knew the kind of people Vivian was leading rarely bothered to look until consequences arrived.

He twisted wire around porcelain insulators with gloved hands, then tightened it, then checked tension, and the metallic note of it ringing taut carried across the open land like a warning bell. When he flipped on the energizer near the pump house, the fence didn’t hiss or spark theatrically, but it produced a steady, rhythmic pulse, a mechanical heartbeat that traveled the perimeter and made the air feel subtly alive. Graham stood where the manicured asphalt of Pinecrest Hollow ended and his dirt began, and he zip-tied warning signs to posts in a neat line that removed any plausible claim of ignorance. He didn’t need to wait long for the first confrontation, because people who believe they own something always arrive fast once they think they’ve won.

A silver luxury SUV rolled up and slowed, and Vivian Ketter leaned out the window behind oversized sunglasses that reflected mountains like trophies. She called Graham’s name as if they were neighbors chatting over a fence, and she asked what he thought he was doing to the “trail entrance” in a voice strained by disapproval. Graham didn’t stop fastening the sign until it was secure, because he had learned that small gestures of refusal matter when someone is trying to position themselves as the authority. When he finally looked at her, he told her he was securing his perimeter because he had livestock and property to protect, and he kept his words steady enough to deny her the satisfaction of seeing him rattle. Vivian stepped out of her SUV, looked at the wire, then at the yellow signs, and then at him, and her mouth tightened as she said it was an eyesore and didn’t match the natural “community aesthetic” they had established.

Graham reminded her that the ranch’s aesthetic was whatever kept the ranch alive, and he added that signs were legally required, because he refused to let her turn safety into a lawsuit against him. Vivian reached out a manicured hand toward the wire as if to test it, and Graham told her quietly not to do it, and the warning landed because even people drunk on entitlement still fear pain. She asked if it was live, and he told her it was a deterrent used all across ranch country, and he pointed out that since she had claimed the land was active-use community space, it was his responsibility to increase safety measures for wandering residents and dogs. Vivian’s expression flushed with anger because he was using her own language against her, and she snapped that the HOA had scheduled a large community picnic on Saturday and that he could not interfere.

Graham told her he wasn’t keeping anyone out because her letter demanded open gates, and his gates would remain open, but the fence would remain hot because his boundaries were not a suggestion. Vivian retreated to her vehicle, promising legal consequences, and Graham answered that he had a lawyer too and that his lawyer cost more than hers, which wasn’t bravado so much as simple arithmetic. After she drove off, Graham sat near the fence line with a thermos and watched the afternoon unfold because he wanted to witness the first moment when entitlement met physics. By late afternoon, joggers arrived in bright athletic gear, talking loudly and ignoring the signs like warnings were decorative, and one man reached to vault the post the way he clearly had before. The shock jolted him, he yelped, and embarrassment colored his face as he accused Graham of electrifying a public trail, and Graham calmly corrected him that it wasn’t a public trail, that there were multiple warning signs, and that situational awareness was a personal responsibility.

As the joggers retreated muttering about lawsuits, Graham’s satisfaction was muted by weariness, because he hated being cast as villain in someone else’s fantasy, but he hated the thought of losing the ranch even more. He repaired spots where people had already tried to interfere with the wire, noting each attempt in a log, and the steady pulse of the energizer felt like a second heartbeat in the air. Near dusk, a boy approached the fence line looking more sad than angry, holding a worn baseball glove and asking for his ball that had rolled into the pasture before the wire went up. Graham felt the tightest knot in his chest loosen a fraction, because this was the human complication he feared most: not the board members, but children being used as emotional leverage. He grounded the pulse safely, stepped over, retrieved the ball, and tossed it back, and when the boy repeated what his mother had said—that Graham was taking away their park—Graham told him gently that he wasn’t stealing anything, he was trying to keep what was left of his own.

The following morning brought sheriff vehicles, because Vivian Ketter was the kind of person who calls authority whenever reality refuses to bend for her. Three patrol cars parked near the subdivision’s welcome sign, and Sheriff Travis Boone approached Graham with the tired seriousness of a man stuck between a neighbor’s rights and a neighborhood’s noise. Vivian stood with a small crowd and an HOA attorney in a sharp suit, pointing at the fence as if it were an act of violence. The sheriff said he was getting reports of an “attractive nuisance” and claims of harm, and Graham answered with calm technical truth, explaining low-voltage, high-impedance agricultural fencing and the legal right to protect livestock and property. Vivian snapped that there were no cows on that ridge, and Graham replied that he had cattle scheduled to graze and that he would be liable if they wandered into suburban streets, which forced the sheriff to acknowledge the point.

Then Graham pulled folded papers from his pocket and said they should discuss “historic use,” and he handed copies to the sheriff and the HOA attorney. The document was a formal notice drafted by Caleb Rourke, stating that if the HOA insisted on classifying the ranch as association-managed community space for decades, then the HOA had accepted responsibility for maintenance and owed Graham for years of labor and liability coverage. The attorney’s confidence faltered as he read, and murmurs rippled through the crowd when Graham stated the amount, because half a million dollars is a number that turns ideals into panic fast. Vivian tried to call it a bluff, but the neighbors began to glance at each other with new unease, because suddenly the “park” looked less like a gift and more like a debt. Vivian swore the picnic would still happen, and Graham watched her leave, knowing Saturday would not be about sandwiches and smiles, it would be about whether a crowd could bully dirt into obedience.

CHAPTER 4: THE WEEKEND THAT TESTED THE VALLEY

Friday arrived with a strange stillness, as if the wind itself had paused to listen. Graham spent the morning in the machine shed cleaning the lenses of security cameras he mounted along the perimeter, because if the HOA wanted a story, he would give them footage so clear it would shame any lie. Caleb Rourke arrived around noon looking sleep-deprived and grim, and he told Graham the board was panicking because the liability created by their own filings was beginning to dawn on them. Caleb explained that if the land were legally treated as HOA-managed asset, the invoice became a balance-sheet problem that could bankrupt their reserves, and if the land was not theirs, the filings could be treated as fraudulent, which carried consequences that go beyond neighborhood drama. Vivian, however, had doubled down, telling homeowners the bill was a scare tactic and insisting the picnic would “cement prescriptive use,” meaning she planned to turn the crowd itself into legal leverage.

Graham watched from the shed door as a crew erected a massive white marquee tent near the roadside, so close to his property line it looked like a challenge planted in soil. He checked energizer levels, verified backups, and moved his cattle into holding pens near the house, because if he needed the unmistakable presence of a working ranch, he intended to have it. As evening fell, music drifted from the subdivision, upbeat and cheerful in a way that felt artificial against open land, and Graham sat in the dark kitchen listening to the fence pulse outside like a metronome counting down. He refused to go to bed early because he knew the night would not calm him, and he refused to drink because he needed his head clear for whatever theater Saturday would bring.

Saturday morning arrived under a bruised sky, purples and steel grays layered like old hurt. By midmorning, vehicles lined the public road, and families poured out carrying blankets, folding chairs, coolers, and the kind of pristine hiking boots that have never met real mud. Vivian Ketter moved through the crowd in a bright red coat, clutching a megaphone as if it were a crown, and she welcomed everyone with a speech about reclaiming the valley’s heart, framing Graham as an obstacle to community heritage. The crowd drifted toward the fence line, and the yellow warning signs were visible, but people treat warnings like decorations when they believe numbers make them immune. A few men approached with bravado and tested the wire with a utensil, jerking back when the spark snapped, and Vivian shouted instructions to drape thick moving blankets over the wire to create a bridge. The method worked just enough at first to create momentum, and the first teenagers scrambled over, cheering as they landed on Graham’s land, as if crossing a boundary were an accomplishment rather than a crime.

Graham stayed on his porch because Caleb had warned him that Vivian wanted footage of him raging, and he refused to give her that gift. Instead, he watched the camera feeds and the timestamped breach, noting faces, dogs, and the spread of the invasion across the north pasture. Within half an hour, his grass looked like a flea market of umbrellas and picnic setups, and dogs were off-leash racing toward the creek. Vivian set up a table on the old salt mound, passing out pamphlets with titles about shared horizons and a future built together, and she lifted a bottle in a mocking toast toward the farmhouse. Graham’s restraint tightened until it felt like a physical cord in his chest, but he kept it, because the trap wasn’t sprung by yelling, it was sprung by reality.

As noon warmed the air, the blankets draped over the fence began to absorb dew, spilled drinks, and damp grass moisture, and what had served as insulation started becoming conductor. Small yelps and curses began to ripple near the perimeter as the pulse found a path through saturated fabric, and Vivian tried to dismiss it as “static pops” while her confidence frayed in her tone. Then a dog bolted toward the fence chasing a scent, hit the wire, barked sharply, and panicked through the crowd, knocking over chairs and sending children crying, and suddenly the “park” began to feel less safe than the suburban lawns they had left. People tripped in badger holes, stumbled on uneven ground, complained about the lack of bathrooms, and started discovering that raw land is not designed to flatter comfort. Graham watched all of it without speaking, because he understood something the HOA did not: land does not perform.

When the afternoon reached the point where discomfort was beginning to turn into resentment, Graham walked to the holding pens and unlatched the heavy gate. He didn’t drive the herd hard and didn’t need to, because cattle follow grass the way water follows slope. Fifty head of Black Angus moved out in a slow, heavy tide, hooves thudding with a rhythm that swallowed the HOA’s pop music, and the sound traveled across the pasture with the unmistakable message of weight. The cows did not charge at people like an attack; they simply arrived, moving toward green patches and stepping where steps made sense to them. A heifer planted a hoof squarely into a plastic container of food, and a steer investigated Vivian’s folding table with the indifference of an animal that does not respect titles, and when the table buckled under a nudge, pamphlets and beverages spilled into dirt and were trampled into slurry. Vivian screamed at the cattle as if volume could intimidate twelve hundred pounds, and the herd answered with low bellows that vibrated in the air, and the crowd’s fantasy began collapsing fast.

People rushed toward the fence line to escape, and in panic many forgot about the wire entirely, and the damp blankets ensured sharp reminders snapped into thighs and hands. The air filled with the thick smell of manure, warm and honest, and the stench alone made some residents gag because suburban life rarely includes that kind of truth. When a cow dropped a steaming pile right where yoga mats had been planned, the symbolism was too perfect to ignore, and even the homeowners who had believed Vivian’s speeches began to look at the pasture with dawning awareness that this was not their stage. Graham finally lifted a megaphone from his porch and told them calmly that the animals were the original residents of the “shared space” they had insisted on, and he reminded them to watch their expensive boots because working ranches produce natural fertilizer. The crowd retreated in a messy surge, dragging damaged gear, shouting at each other, and trying to keep children from stepping in holes, and the “community picnic” didn’t end neatly so much as evaporate into a frantic exit.

CHAPTER 5: THE BILL THAT TURNED FRIENDS INTO CREDITORS

When the last families spilled back across the road, the north pasture sounded like it belonged to itself again, filled with the contented tearing of grass and the steady breathing of cattle. Vivian Ketter remained near the salt mound with mud on her coat and panic in her posture, and the collapse that mattered most was no longer happening in the field, it was happening among her own board members. The HOA treasurer, Derek Lang, stood by the roadside with papers in his hands and a face drained of color, and he called Vivian’s name with a tone that had lost all deference. Vivian tried to redirect him toward calling the sheriff, claiming livestock endangerment and safety violations, but Derek snapped that cows weren’t the problem anymore, because the documents Caleb served had turned her “annexation victory” into a financial disaster.

Homeowners clustered around Derek, no longer looking at Graham like he was the villain, but looking at Vivian like she might have set their savings on fire. Derek explained, loudly enough for the crowd to hear, that Vivian’s filing had legally framed the pasture as HOA-managed asset for years, which meant the association could be liable for the maintenance costs Graham invoiced, and the numbers were beyond ugly. When someone asked how much, Derek said the figure out loud, and the sound of it sucked oxygen from the group, because half a million dollars isn’t a symbolic number, it’s a number that arrives as a special assessment on families who budget carefully. He added that divided among the homes, the cost would translate into thousands per household, and suddenly the “shared horizon” pamphlets looked like weapons used against their own wallets. Another homeowner asked what happened if they dropped the claim, and Derek answered that then they were admitting to trespassing and fraudulent filings, and the president who signed those documents could be personally liable.

Vivian’s mouth moved, but her polished speech failed her because there is no elegant way to talk when your audience becomes your creditors. Homeowners began shouting that she had promised a win-win, that she had said the land was theirs for the taking, and their outrage turned inward the way crowds always do when they realize they’ve been misled. Graham stood across the fence line watching without joy, because watching a neighborhood turn into a pack isn’t pleasant, but he did feel justice in the shifting weight of reality. When Derek approached the fence and asked for a man-to-man talk, he kept his distance from the wire like a person who had finally learned to respect boundaries. Derek asked what happened to the invoice if the HOA retracted the claim, and Graham told him that if the ranch was acknowledged as private, then there was no “service” owed and the invoice could disappear, and that forgiveness was possible if the board made the record right permanently. Relief moved through the nearby homeowners like the first warm breath after a near miss, because the bullet of that assessment had just whistled past their ears.

Derek announced an emergency meeting and demanded Vivian step down, and the crowd’s silence around her turned cold, the kind of silence that isolates a person more than shouting ever could. Vivian walked away toward her vehicle with her coat stained and her posture shrunk, and she drove off without looking back, disappearing into the subdivision that had once applauded her. The homeowners dispersed slowly, gathering ruined blankets and broken chairs, and they looked at the ranch not like a playground anymore but like a line they had no right to cross. Graham watched until the road cleared, then he turned off the fence energizer, not because he was surrendering, but because the lesson had been delivered, and he no longer needed electricity to say what the dirt had already proven.

CHAPTER 6: THE DUST THAT OWNS ITSELF

The emergency meeting took place at the Pinecrest Hollow community center, a room that smelled of floor wax and nervous sweat, lit by harsh overhead panels that made everyone look tired. Graham sat in the back row with his hat on his knee, denim and boots out of place among fleece vests and polished shoes, and he didn’t speak until someone forced his name into the conversation. Derek Lang stood at the podium looking as if he had aged a year in a weekend, and he told the packed room that the board had reviewed the filings and that the association faced two ugly choices: a long legal battle that could drain reserves and potentially create personal liability, or a settlement that restored boundaries and prevented financial catastrophe. When a resident asked what the settlement required, Derek looked toward Graham and said the HOA would sign a permanent, irrevocable boundary recognition, formally acknowledging that Parcel 117 had never been, and would never be, association property.

Voices rose immediately urging the board to do it, and the sound had less to do with principles and more to do with survival, because people become reasonable fast when ruin is visible. Derek added that the association’s records were a mess, that fees had already been spent on legal moves that now looked reckless, and that the remaining board members wanted out because nobody wanted to steer a ship built on someone else’s mistake. In that tense vacuum, someone said that Graham knew the land and the truth, and another voice suggested that the only person who hadn’t lied might be the one who could end the crisis cleanly. The irony was bitter, but desperation often creates strange alliances, and the room’s murmurs gathered around the idea like a tide.

Graham stood and walked to the front with slow, grounded steps, and the echo of his boots on the community center floor sounded like a reminder that reality had arrived in the building. He told them he did not want their titles and did not want their committees, but he would accept temporary authority long enough to call one final vote, because the valley did not need another miniature government built from aesthetics and entitlement. He took the gavel Derek offered, and it looked small in Graham’s hand, and he said plainly that he moved for the Pinecrest Hollow HOA to dissolve permanently, returning ownership and responsibility to individual homeowners rather than a board that could weaponize paperwork against neighbors. He told them that land and people should be connected by direct conversation and clear lines, not by threats and dues and manufactured authority, and he added that if they truly wanted community, they could build it without stealing it.

The silence after his motion lasted only a breath before voices rose in approval, because even the homeowners who had enjoyed the HOA’s convenience were now sick of its power. The vote was overwhelmingly in favor, and when Graham struck the gavel once, the association’s authority ended in that room, not with violence, but with collective refusal to keep feeding a machine that had tried to eat the valley. In the week that followed, the marquee tent vanished, the subdivision quieted, and the ranch returned to its steady rhythm. Graham turned the fence off but left the posts as a reminder, and he unchained the gate because boundaries don’t require hostility when they are respected.

One evening, Graham grilled steaks on the porch while Caleb Rourke leaned on a post with a cold beer, and Walt Granger laughed about Vivian Ketter’s sudden disappearance from town life, because people who attempt to rule by paperwork often flee when the paperwork bites back. Derek Lang showed up too, looking lighter in old jeans, helping flip meat and talking less like a treasurer and more like a neighbor. They looked out over the pasture where cattle moved slowly under a sky turning gold, and Derek admitted the valley felt different now, quieter and more honest. Graham told him it felt like the land belonged to itself again, and the sentence wasn’t poetry, it was the plain truth of a man who had spent his life reading dirt.

At the end of the drive, kids played ball in the street, and one hit a fly that sailed over the fence and landed in tall grass. The boy hesitated at the boundary, looking toward the porch with the careful fear of someone who had heard adult arguments and didn’t know what was safe. Graham waved him in and told him to grab it and watch his step, and the boy ran into the pasture laughing, weaving around cow pies like a child learning the difference between a park and a ranch without being punished for curiosity. Graham watched the kid return, then turned back to the grill and the people beside him, and he understood something simple that the HOA had forgotten: the ground doesn’t remember masters, but it remembers who treats it like life instead of decoration, and the valley was finally learning that lesson the hard way.